views

- Establish clear, reasonable rules based on your child’s age and circumstances, and use “if...then” style language to explain the consequences of breaking the rules.

- Prioritize natural consequences for bad behavior. For example, if your child broke a vase, have them clean the mess and save up to buy you a new one.

- Grounding them from using social media is an effective punishment, but making them miss their big basketball game or recital should only be done with much consideration.

Defining Conditions and Consequences in Advance

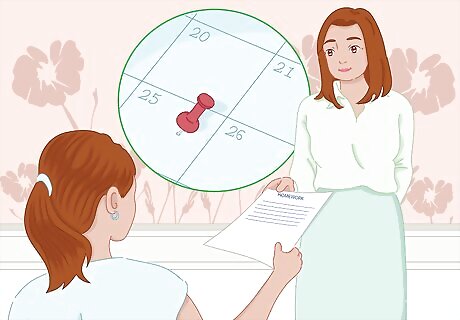

Lay out specific, relatable, achievable expectations for behavior. Vague directives like “be good or you’ll be in trouble” or “you better shape up if you don’t want to be grounded” don’t give kids enough information to form a clear understanding of conditions and consequences. Establish clear rules that are reasonable based on your child’s age and circumstances, and use “if...then”-style language to lay out the consequences of breaking the rules. “You aren’t allowed to play video games for an hour after you get home from school, because this is homework and study time.” “If you break this rule, you will not be allowed to play video games for a week.”

Keep the focus on short-term expectations. Kids and teens tend to focus on the here-and-now, so giving long-range directives won’t be as effective. Instead of saying “you have to give your best effort in history class this year,” focus on the week or two ahead: “you have to keep up on your homework this week and start studying for next week’s test.” Think of it this way: many kids are told they need to be good all year if they want Santa Claus to bring them lots of presents, but they usually only really start to worry whether they’re on the “naughty” or “nice” list come December!

Prioritize natural consequences for bad behavior. Like the common saying “the punishment should fit the crime,” consequences for bad behavior should connect in some way to the misbehavior itself. This makes it easier for kids to understand the cause and effect of their actions. It also makes it easier to create punishments that are proportionate to the misbehavior. For instance, if your teenager engaged in some minor vandalism with a couple of friends, you might “ground” them specifically from seeing those friends for 2 weeks, in addition to requiring them to apologize and help clean up.

Discipline based on intent more than results. The results of a child knocking over a vase while wrestling with their brother, and a child who throws a vase in a fit of anger over not getting their way are the same—a broken vase. But, while each is worthy of some kind of punishment, the intentional destruction of the vase in the second case should result in a more extensive punishment. If you always use a blanket punishment like “you’re grounded for a week” and don’t factor in intent and other extenuating circumstances, your child will focus more on how unfair the punishment seems, rather than learning from the experience.

Making Sure Grounding is Fair and Effective

Limit or avoid grounding before a child is 10-12 years old. Grounding isn’t particularly impactful before a child starts to develop strong connections and an identity outside the home. That is, most kids under 10-12 won’t really see grounding as much of a punishment. For somewhat younger kids, though, very targeted “groundings”—banning them from playing with a certain toy or doing a certain activity, for instance—may be effective. Kids under age 6, or maybe even up to 8, likely won’t be able to perceive the cause-and-effect connection between their misbehavior and their grounding.

Ground them in a targeted manner. You want the grounding to be an unpleasant experience so the kid will not want to repeat it, but overdoing it will cause their resentment to obscure the message you’re trying to get across. Ground them from places/things/people that will “hurt” to miss out on, but don't necessarily cut them off completely from their peer groups and important activities. Grounding them from going out, having friends over, or using social media at all hours of the day can be plenty unpleasant. Making them miss their big basketball game or their dance recital as part of a blanket weeklong grounding should only be done with a lot of thought on your part.

Limit grounding to a week or a few weekends. Open-ended or long-term groundings also tend to create more resentment than they do understanding. If they’ve misbehaved to such a degree that a weeklong grounding, or one that covers multiple weekends, seems inadequate, other disciplinary options should be considered. If they took the car without permission and damaged it, you might ground them for a week initially, and during that time formulate a plan for them to work off the repair cost.

Take special care with grounding from social media. It may be tempting to ban all social media activity or confiscate their phone during a grounding. However, make sure you realize how extensive of a punishment this might be. Many kids get important information (e.g., school, extracurriculars, etc.), news, and a large part of their connection to the outside world via social media. Taking social media away completely as part of grounding may cause more resentment and anxiety than you think, and it could lead to excessive use after the ban is lifted. Instead, consider whether a targeted social media “grounding”—limiting it to certain times or activities—might be sufficient.

Give them opportunities to reduce their grounding. Keep in mind that giving them “time off for good behavior” is not the same as relenting on a given punishment, though. Give clear details on what they need to do in order to reduce their grounding, and do not waver from your original decision if they do not follow through. For instance: “Since you broke curfew again, you are grounded for the next 2 weekends. However, if you do this list of extra chores, in addition to your normal chores and all your schoolwork, I’ll reduce it to 1 weekend.”

Seeking Alternatives to Ineffective Grounding

Make a transition to “empathic parenting” techniques. Empathic parenting replaces traditional punishments like grounding with a communication-based approach. The goal is to help the child see what they did wrong and why, and to give them the means to choose how to “fix” things. Some proponents of empathic parenting believe that grounding is never justified, while others believe it can be used in a limited fashion alongside empathic parenting techniques. One way to practice empathetic parenting is to ask your child about their choices. For example, if your child makes a wrong choice, ask them about why that was the wrong choice and what a better choice might have been.

Focus on open communication instead of punishment. Instead of grounding your child for failing a test because they went out with their friends instead of studying, try seeing things from their perspective and asking leading questions: “I know it can be hard to say ‘no’ to your friends when you’re trying to fit in at a new school. Can you tell me about how you felt afterward, when you realized you wouldn’t have time to study?” If they’re not yet ready to accept their responsibility and come up with a solution, give them some time and re-open the dialogue again later.

Empower your child to develop a “fix” for their error. After you’ve communicated freely about the misbehavior, give them the opportunity to come up with a way to address the problem. Doing so makes your child an active participant in the learning opportunity that mistakes present. For instance, in the example of failing a test because they skipped out of studying to hang out with friends, you could say “I’d like you to take some time to come up with a plan for how you might be able to bring your grade back up. Let me know how I can help you.” Make sure to talk with your child at a time when they are not feeling emotional about the issue. It’s okay to take a break until they are calm.

Don’t be ashamed to seek professional guidance. If grounding doesn’t seem to make any difference, empathic techniques aren’t doing any better, and you’re out of ideas, consider finding a child therapist or family counselor. A trained, experienced, licensed professional may be able to provide you with new ideas and strategies that could help with your child’s discipline problem. Talk to your or your child’s doctor, the school guidance counselors, trusted friends, and/or your insurer to get leads on good therapists in your area. The therapist may suggest techniques such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Comments

0 comment