views

Assessing Consciousness Level in a Responsive Person

Size up the scene. The first step in any emergency situation is to stop and assess the situation. See if you can determine what caused the injury to the person and if it is safe for you to approach. It doesn't help anyone to rush into a situation before the hazard has completely ended — you can't help the person if you fall victim to the same emergency, and emergency medical services (EMS) do not need to rescue two people instead of one.

Recognize signs of when a person may be losing consciousness. These include: Slurred speech A rapid heartbeat Confusion Dizziness Lightheadedness Uncoordination Suddenly being unable to respond coherently, or unable to respond at all

Ask the person questions. A series of questions will immediately give you a lot of information regarding the person’s state. The questions should be easy while still requiring a level of basic cognition. Begin by asking the person if he’s all right to see if he’s responsive at all. If the person responds or even groans to show that he’s not unconscious, try asking: Are you okay? Can you tell me what year it is? Can you tell me what month it is? What day is it? Who is the president? Do you know where you are? Do you know what happened? If the person answers clearly and coherently, then they are displaying a high level of consciousness. If the person responds but answers incorrectly to several of the first questions, then he’s conscious but showing signs of what is called an altered or changed mental state, which includes confusion and disorientation.

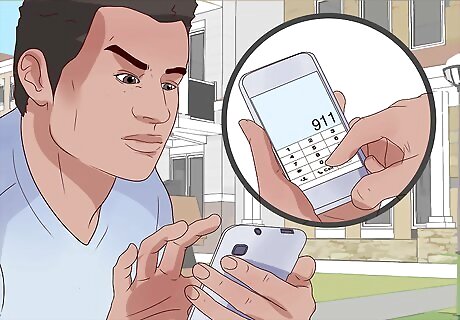

Call 911. If the person is conscious but showing signs of an altered mental state (such as being unable to clearly answer simple questions), then you should call 911 immediately. When you call 911, inform them of the patient's score on an AVPU scale: A — Alert and oriented V — Responds to Verbal stimuli P — Responds to Painful stimuli U — Unconscious/no response Even if the person responds coherently to all of your questions and shows no signs of an altered mental state, you should still call 911 if the person: Has other injuries from the traumatic event Feels chest pain or discomfort Has a pounding or irregular heartbeat Reports impairment to vision Cannot move her arms or legs

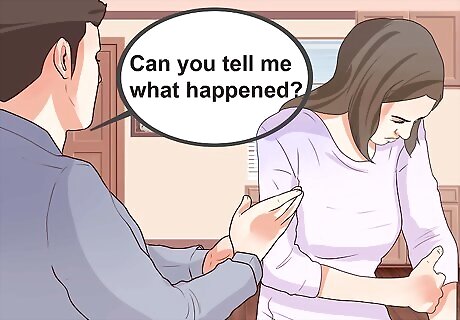

Ask follow-up questions. This is useful to see if you can gather any clues as to what caused the person to either pass out or have a diminishing level of consciousness. The person may or may not be able to answer any of these, depending upon their level of consciousness and how responsive they are. Try asking: Can you tell me what happened? Are you on any medications? Do you have diabetes? Have you ever experienced a diabetic coma? Are you on any drugs or have you been drinking? (You may want to look around for any signs of needle marks on arms/feet or bottles of medication of alcohol nearby) Do you have a seizure disorder? Do you have a heart condition or have you ever had a heart attack? Did you have chest pain or any other symptoms prior to going down?

Keep track of all the person’s answers. The person’s answers—whether logical or nonsense—will help the emergency responders determine the best course of action. Write everything down if you need to in order to pass along the information just as the person communicated it. For instance, if the person has given incoherent answers to most of your questions but also communicated that she has a seizure disorder, then she may continue answering questions incorrectly for five to ten minutes in the post-seizure phase of the disorder, yet she may require little more than a brief period of observation from paramedics. As another example, if the person has confirmed that she is diabetic, then the emergency responder will know to immediately check her glucose levels when you pass along that information.

Keep the person talking to you. If the person has provided incoherent answers to all of your questions—or if he’s given logical answers but seems on the verge of nodding off—then do what you can to keep the person talking to you. Emergency responders will have a much easier time assessing the situation if the person is conscious when they arrive. Ask the person if they can keep their eyes open for you, and ask him additional questions that encourage him to keep talking.

Be aware of other common causes of unconsciousness. If you know the person or witnessed her "pass out," you may be able to provide emergency medical staff with clues as to the diagnosis or "cause" of unconsciousness. Common causes of diminished consciousness or loss of consciousness include: Severe blood loss Severe injury to the head or chest Drug overdose Alcohol intoxication A car accident or other major injury Blood sugar problems (as in diabetics) Heart problems Low blood pressure (common in the elderly, but they usually regain consciousness shortly thereafter) Dehydration Seizure Stroke Hyperventilating

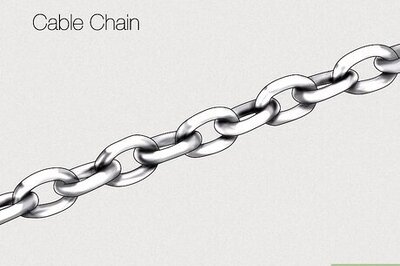

Check the person for a medical alert necklace or bracelet. In the event of many medical conditions—such as diabetes—the person may wear something like this to inform the condition to responders. If you find one, report it immediately to emergency medical personnel when they arrive.

Monitor the person until emergency medical personnel arrive. It is important to have someone watching over the patient at all times. If he remains semi-conscious and appears to be breathing and not in any distress, continue to watch him until medical staff arrives. If the person becomes totally unresponsive, the situation is much more serious and you will need to assess him further and proceed with the steps below.

Assessing an Unresponsive Person

Attempt to wake the person with a loud noise. Try yelling, "Are you okay?" and shake the person gently. This may be all it takes to bring the person back to consciousness.

Administer painful stimuli. If the person is unresponsive to your questions, but you are not sure whether they are "unconscious" to the degree that requires CPR, do not administer a painful stimulus to see if it produces a conscious reaction. The most common form of this is a "sternal rub," which entails making a fist and using your knuckles to rub vigorously into the person's sternum or breastbone. If the person responds to "pain" — to this sensation — you can continue to monitor them without CPR as this is a sign that they are okay for the moment (if they do not respond to pain, however, you will likely need to proceed to CPR). If you fear the person otherwise has a chest injury from the trauma, other methods of testing her pain response include pinching the person’s fingernail or nail bed or pinching the person’s trapezius muscle (back of the neck). The pinch should be very hard and directly to the muscle. If the person responds to the pain by either curling all her limbs in or out, this is referred to as posturing and could be indicative of spinal injury.

Ensure that you have called 911. You likely have already done this, but especially if the person is unresponsive to pain, you need to make sure that an ambulance is on the way. Remain on the line with the operator, or if someone else is there, hand the phone to him so he can receive further instruction.

Check if the person is breathing. If the person is unconscious but breathing, then you may not have to perform CPR, especially if no one around is certified in the practice. Be sure to keep a constant watch on the rise and fall of the person’s chest to ensure that he’s still breathing. If you cannot tell by watching alone, you can place your ear near their mouth or nose and listen for breath sounds. When you listen at someone's mouth, point your head down their body to the chest and watch their chest rise and fall at the same time. This is the easiest way to see breathing. Note that if you have any reason to suspect a spinal injury but the person is breathing, then do not try to reposition him unless he vomits. In this case, roll their entire body to the side while supporting their neck and back to keep them in the same position. If you have no reason to suspect a spinal injury, then roll the person onto their side, position their top leg so that both their hip and knee are at a 90° angle (to stabilize him on their side), and then softly tilt their head back to help keep their airway open. This is called the "recovery position" and is the safest for the patient to be in, in case he vomits at any point.

Check for a pulse. You can check the person's pulse on the underside of her wrist on the thumb side — called the "radial pulse," or by gently feeling one side of their neck about an inch below their ear — called the "carotid pulse." Always check the carotid pulse on the same side of the body on which you are sitting. Reaching across the neck of a patient for their pulse can cause panic if they wake up. If a pulse is absent at any point, and especially if there is no breathing, now is the time to start CPR if you are trained; if not, follow instructions of emergency medical personnel over the telephone. If you accidentally hung up after initially calling them, you can call back at this point for further instructions. They are trained to provide instructions for laypeople over the phone.

Giving CPR to a Person Without a Pulse

Ask if anyone around knows CPR. Cardiac arrest is one of the most common reasons for a person to collapse and become unresponsive for no other obvious reason, such as due to a car accident. Providing CPR (if necessary) while waiting for the arrival of paramedics can double or even triple a person’s chance of survival in the event of cardiac arrest. Find out if anyone in the immediate vicinity is CPR certified.

Check the person’s airway. If the person isn’t breathing or has stopped breathing, then the first step is to check their airway. Place one hand on their forehead and the other underneath their jaw. With the forehead hand, slide their head backward and tilt their jaw with the other hand. Watch for any signs of their chest beginning to rise and fall. Place your ear over their mouth and feel for any breath on your face. If you can easily see something in the airway when you look into the person's mouth, then try to remove it, but only if the object is loose. If the object is clearly lodged, then do not try to remove it from their throat since you may inadvertently push the object farther down their airway. The reason we check the airway first is that if there is a blockage (or an obstruction, such as often happens in choking victims), and if we can easily remove it, our problem is solved. However, if there is not, check for a pulse and, if there is no pulse (or if you cannot find one and are in doubt), immediately begin chest compressions. Head-tilt chin-lifts should not be done on skull, spine, neck injuries. Instead, use the jaw-thrust method, in which you kneel above the person's head and place your hands on either side of their head. Place your middle and index finger along their jaw bone and gently push it upward so that the jaw is jutting forward, as though he has an underbite.

Perform chest compressions. Current CPR standards place the emphasis on chest compressions with a ratio of thirty compressions for every two rescue breaths. Begin chest compressions by: Placing the heel of your hand on the person’s breastbone directly between their nipples Placing the heel of your opposite hand over the top of the first Positioning your body mass directly over your positioned hands Compressing hard and fast downward approximately two inches into their chest Allowing their chest to rise completely Repeating to a count of thirty At this point, add in the two rescue breaths if you are trained in CPR. If you are not, continue with compressions and ignore the breaths as they are much less important.

Check for signs of breathing again (reassess the person for breathing approximately every two minutes). You can stop performing CPR as soon as the person shows signs of breathing on their own. Watch for the rise and fall of the person’s chest and place your ear near their mouth to check if he’s breathing on their own.

Continue CPR until paramedics arrive. If the person continues to show no signs of consciousness or breathing on their own, then keep performing CPR at a rate of two rescue breaths to every thirty chest compressions until emergency responders arrive.

Comments

0 comment