views

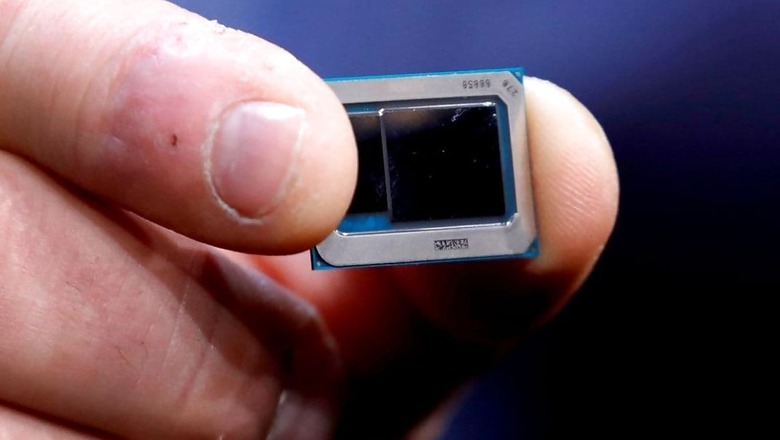

Semiconductors. Chips. You craved for all sorts of smartness with gadgets. You got all sorts of smartness with gadgets. From your toothbrush to your new car. What makes all this work? Chips. They are the backbone of pretty much everything around you. Be it your laptop or PC, your TV, your smartphone or even the good old Wi-Fi router you have at home, everything uses these to work. As does your car, and the newer the car, the more chips it is likely to integrate. You may have noticed over the past few months that the laptop you may have been eyeing is mostly showing as out of stock. And the car that you’ve booked, you’ve been quoted a waiting period that’s around 6 months, if not more. The common thread—the chips that make these smart, are in short supply. Serious chip anxiety, globally, across industries.

There has been a semiconductor shortage for a while now, something we have written about earlier as well. That was a few months ago. The thing is the semiconductor shortage continues to be as severe as before. Supply chains are stuck, production lines have slowed down and while new products and cars may be getting launched, there isn’t enough stock for everyone to buy right away. For us consumers, the ground reality of all the complexity of reasons is two pronged, maybe three. You’ll either simply not be able to buy what you need to because it is not in stock, or you may have to wait much longer to get your hands on your order. Even so, there could be a chance that you’ll be paying a higher price than what you bargained for, as input costs for companies and manufacturers have gone up, and some of that will be passed on to customers. “While the chipset shortage is impacting several sectors including PCs, we are constantly working on ways to ensure smooth supply of products and devices to our end users,” Vickram Bedi, Senior Director, Personal Systems at HP India, had told News18 last month, when asked about how the chip shortage is impacting the laptop production lines. Multiple reasons for this shortage, including the COVID pandemic, semiconductor manufacturing expansion not happening at pace enough to meet existing demand and Bitcoin.

How Bad Are Things In The Shops? The shortages of semiconductors are impacting everyone. Samsung had said last month that the chip shortages are hitting the TV and appliance business. Earlier, the company had hinted that there may not be newer versions of the Galaxy Note smartphone line-up. “What it will mean is they can’t get something, or prices are slightly higher,” said Alan Priestley, an analyst at Gartner, while speaking with CNBC in the US, last month. In India, there are incredibly long waiting times being quoted by dealerships if you walk in now to book a new car—even longer if the car is very popular and in high-demand. You may still be unable to get your hands on a new Sony PlayStation 5 or Microsoft Series X or Series S gaming console. Smartphone makers including Apple have repeatedly said that sales of new phones have been impacted by the shortage of components. Qualcomm, the world’s largest chipmaker for smartphones and mobile devices, has earlier said that the industry’s reliance on a handful of semiconductor manufacturers is hurting business.

What are semiconductors And Just Why Are They So Important? I am absolutely not an expert at the science of semiconductors. Best to let tech giant Hitachi explain what semiconductors are—”Semiconductors possess specific electrical properties. A substance that conducts electricity is called a conductor, and a substance that does not conduct electricity is called an insulator. Semiconductors are substances with properties somewhere between them. ICs (integrated circuits) and electronic discrete components such as diodes and transistors are made of semiconductors. Common elemental semiconductors are silicon and germanium. Silicon is well-known of these. Silicon forms most of Ics. Common semiconductor compounds are such as gallium arsenide or indium antimonide.” This is why these semiconductors are an integral part of pretty much every electronic appliance that you may use at home, or for any infrastructure that you may use inside or outside your home.

What all uses semiconductors and silicon chips? Answer: A Lot Of Things. The list is long. Your smartphone, your TV, your refrigerator, the new AC that you purchased ahead of the summer, laptops and PCs, smart speakers, tablets, gaming consoles such as the Sony PlayStation 5, lamps and bulbs, children’s toys, washing machines, rice cooker, microwaves, water purifiers, air purifiers, induction cookers, fast chargers, wireless chargers, Bluetooth speakers, water heaters, your internet modem and Wi-Fi router—pretty much everything you see around you in your home uses semiconductors to be able to do whatever it is that they are meant to do. It seems that most things, except for your bottle of moisturizer, the shower gel and the cutlery on the dining table, use some sort of smartness from silicon chips.

Step out of your home, and there are crucial semiconductors in your car, your bank’s ATM machine, communications infrastructure that your mobile company has set up for 3G and 4G, that 5G network you keep demanding, public transport, the backend systems of apps that we all use on your phone, that credit card machine you swipe your card with to complete a shopping expedition at a store, a lot of the hospital equipment, and more. And this is just a pretty concise list, while at it.

During the quarterly earnings call in January which saw Apple set revenue records and robust sales including of the newest iPhone 12 series, the company was still feeling the impact of supply chain constraints. Apple CEO Tim Cook told reporters at the time that “semiconductors are very tight” along with short supply of other components too. “The current chip shortage all starts with the unprecedented demand for personal computers and peripherals as the globe worked and attended school from home,” Patrick Moorhead, founder of Moor Insights, told CNBC earlier.

So, what really are the reasons for the chip shortage? It is a multitude of reasons that have led to the global semiconductor scarcity. The trigger was the COVID-19 pandemic. The demand for laptops, PCs, phones, tablets and peripherals such as monitors, modems and Wi-Fi routers, printers, webcams and work from home (WFH) accessories saw a global surge and computing as well as peripheral device makers struggled to keep up. “The shortage in the semiconductor industry is across the board,” Qualcomm’s CEO Cristiano Amon, had warned in February that it isn’t just a shortage of the newest or the fastest chips, but every chip that’s being used in tech products, appliances and cars.

At the same time, as the pandemic ushered in lockdowns and slowdown in demand for a lot of product categories, companies scaled back production and at the same time, cut orders for chips. In particularly automobile companies, and those orders were quickly reserved by smartphone and computing device makers, for instance. More so in the case of auto companies, because demand bounced back much sooner than expected. In some cases, such as computing devices and home appliances, not just a normalcy but significantly higher demand. This left them at the back of the queue when they went back to place their fresh orders for chips.

Global Climate Hitting Semiconductor Manufacturing: Apart from the COVID-19 pandemic causing confusion for multiple industries, two extreme climate scenarios unfolding in different parts of the globe have hit semiconductor production hard, leading to further backlogs. For large parts of February, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) and Samsung struggled with manufacturing at their facilities in Taiwan due to a drought in the region. Soon after, Samsung’s S2 Fab in Austin, Texas has to slow down production due to the extremely cold weather which blew through the state, impacting electricity supply. This also indicates a geographical concentration problem. More than 70% of the world’s semiconductors are manufactured by TSMC and Samsung, that’s according to market share numbers from Q2 2020. Both of these manufacturers rely heavily on their facilities in Taiwan.

Consumption patterns vs Demand: Has semiconductor manufacturing capacity increased every year to keep pace with the demand? The answer seems to indicate a skewed ratio. Research firm McKinsey says that while semiconductor manufacturing capacity has seen a stead annual increase of around 4%, semiconductor utilization has been around 80 percent in the past decade. “While the semiconductor industry has increased its production capacity by nearly 180 percent since 2000, its total capacity is nearly exhausted at the current high utilization rate,” they say.

Of Course, It is 2021 And Bitcoin Has To Insert Itself In Everything: Bitcoin and cryptocurrency is in vogue this year. Fair enough, but the problem is, crypto needs a lot of processing power to work. That has meant cryptocurrency miners are buying graphics cards and processors, in large numbers. So much so that Nvidia has to cut down the hash rate (mining efficiency) of the GeForce RTX 3060 graphics card in half for Ethereum miners, via a software update, to ensure there is enough supply for gamers. All this has also meant that prices of graphics cards, alongside dwindling availability, have shot up. “Added demand from cryptocurrency miners is coming when the chip industry is dealing with simultaneous crises — from supply constraints to a structural shortage of high-end chips. The squeeze should last through the end of the year,” said CW Chung, head of research at Nomura, while soaking with The Financial Times. He goes on to explain how the Bitcoin and crypto currency rally earlier this year, led to a situation where demand from crypto miners represented a tenth of the entire sales of TSMC, the third-largest chipmaker in the world.

Donald Trump and the Trade War With China: The semiconductor shortage may not have been this acute if it wasn’t for former US President Donald Trump’s trade war with China that had tech companies including Huawei in the middle of it all. As new regulations began to roll in, Huawei and other Chinese tech companies knew that sanctions would impact their ability to purchase chips and components for products it may want to sell in other countries. Thus, the reported stockpiling, for their 5G smartphones and tech products. The trade war also meant US tech companies couldn’t but chips from the likes of the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation based in China—the company was blacklisted by the Trump administration.

It was October last year when Bloomberg first reported Huawei quietly stockpiling critical chips to keep supplying the Chimene mobile networks with 5G technology for the next 12 months or so, at least. “Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. began ramping up output in late 2019 of Huawei’s 7-nanometer Tiangang communications chips, the most crucial element in 5G base stations, people familiar with the matter said. The Taiwanese contract manufacturer eventually shipped more than 2 million units at Huawei’s behest ahead of the sanctions cutoff last month,” the report said.

What is the way forward? First and foremost, patience. This will take time to ease out, and in the meantime, there isn’t much you can do. Secondly, more manufacturing avenues will help in the coming years, as demand is expected to continue to see high growth. The European Commission, the executive arm of the EU, has said it wants to build up chip manufacturing capacity in Europe. Chipmaker Intel has already shown interest in setting up a semiconductor factory in the region. At the same time, TSMC has said it will invest $2.87 billion to expand the capacity at its production facilities in Nanjing, China, which should begin production in the second half of 2022. It was in April that the company had confirmed plans for investing $100 billion over the next three years. Intel announced in May that they would invest $3.5 billion to expand the facilities in New Mexico in the US as well as investments in manufacturing facilities in US states of Arizona, Oregon, as well as in Ireland and Israel.

Is the shortage expected to end anytime soon? The answer is no. Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger has already said that he expects the shortage to last another couple of years. European chipmaker NXP Semiconductors has said that it’ll not be before 2022 that the situation sees some easing off. “Our current expectation is that we will face a tight supply environment for at least the remainder of 2021,” said NXP CEO Kurt Sievers, during a conference call.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here.

Comments

0 comment