views

I was four or five when I saw a journalist on screen, for the first time. Seema Soni burst into the screen in a red and white dress, her hair tied in two braids, fastened by red ribbons—holding a file and checking on slacking co-workers. Tired of people not doing their work and apologising to her, she mumbles to herself, walks into the Editor’s office and submits her article. She knows she has not met her deadline and she is apologetic; her landlord’s children make too much noise, don’t let her work in peace and she has had it with them.

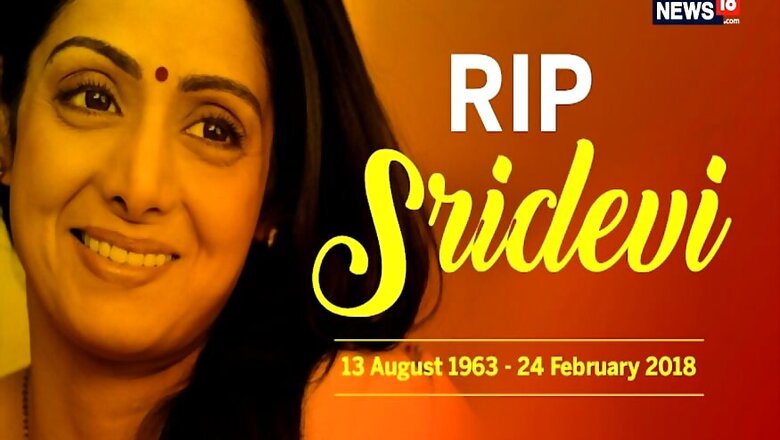

At that point in time, sitting in a Calcutta living room, I knew I wanted to be a journalist. Mr India released in 1987 and, like most people who grew up in the early 90s, I watched that film some fifteen times, thanks to the recurrent reruns on the Doordarshan channels.

Sridevi played Seema Soni in the film, in love with the eponymous invisible vigilante, Mr India, and working as an undercover journalist and activist to bring an end to the many social terrors engineered by the supervillain, Mogambo and his cronies. In the course of her exposé, she wears a hat laden with fruits pretending to be an exotic singer-dancer, sways and sings, and gifts me my favourite song from childhood, “Hawa Hawaii.”

Everything about Seema Soni became a favourite; the golden headdress, the big earrings and the wet blue chiffon sari that hugged her frame. I sang along with her—the string of nonsense words from the song’s prelude—and copied her dance steps, with my mother’s dupatta wrapped around me like a sari. I wanted to live in Mr India, and live as Seema Soni.

Seema Soni and her hairdos soon gave way to a more “mature” line of unicoloured chiffons and string of pearls, matched with straight blow-dried hair in Chandni (1989) and my five-or-six-year-old attention span soon waned. A few years later, when Sridevi took a post-marriage retirement from films, I didn’t take long to change camps and promptly become a Madhuri Dixit (and for some strange reason, Mamta Kulkarni) fangirl.

It took years for me to get to an age when watching Lamhe (1991) would be alright, and eighteen years after film’s release, sitting in my hostel room in Delhi, the fangirl reappeared. There were things Sridevi could do with her face that no one else could; a slight twitch of her nose, a raise of an eyebrow, curling her lips and sometimes, a half smile. She had a face that was so elastic and so rich with expressions that it seemingly took her nothing to play Charlie Chaplin and make a three-year-old laugh till she wept, and then go on to sway in love and longing for an invisible lover and turn a generation of adolescent boys into men—all in the course of half an hour.

It is said that Shekhar Kapur, when shooting “Hawa Hawaii” wasn’t sure where to place the camera; if he focussed on her face, he felt he would lose out on her toes. When she danced, she danced with her whole body—so much so, that Kapur felt even her toes were emoting. One could probably make a documentary on just what she does with her eyes, with her face placed between her heavily bangled arms, within the five minutes of “Mere Haathon Mein Nau Nau Chudiyaan Hain.”

Many other actresses danced, acted and loved like Sridevi did, but nobody quite made us laugh like her. Again, with that repository of a face, she appears as Manju (and Anju) in Chaalbaaz (1989) and wreaks havoc in the lives of her terrible relatives, complete with a comic timing that goes unmatched till date. The unabashedly feminine Sridevi, the goddess of romance duly clothed in chiffons, walked into comedy, a largely male-dominated domain, and made it her own like very few have been able to. It is a matter of celebration then, when we are still talking about female actors not being paid as much as the male ones, that Sridevi demanded to be paid as much as Amitabh Bachchan, the highest earning actor back then. Sridevi’s radicality lay in making it to being the first female superstar in an industry that didn’t even speak her language, and getting paid the most while at it.

At the behest of two of my friends, I watched English Vinglish (2012) last night. As she strutted around in her block printed cotton saris on the streets of Manhattan, I saw bits of my mother on-screen—flustered by the number of coffee options in a cafe, fumbling at the metro turnstile and clutching herself tight while trying to speak English to Americans in a strange city. Sitting in Manhattan, the fangirl had run her full course. Twelve years back, I wanted to be everything Sridevi was and today, she stood for everything my mother perhaps wanted to be, when she took her Downtown N trains to come see me at school. That is the crazy range of the first Indian female superstar!

I remembered the scene from Mr India when she brings in boxes of samosas, chips and pastries into a room full of starving children; dressed in white, she looks around and ask, “Kya khayenge? chips, samosa…” then stops to lick her fingers and resumes, “...pastries?” and cried like I did when I first watched it. The bringer of chips, samosas, pastries and much laughter and beauty, is gone.

Maybe not too far. Maybe all we really need to do is look hard through a piece of red glass.

(Author, a resident of New York, writes on films, food, gender and most other things. Views are personal)

Comments

0 comment