views

Two issues dominated the political discourse in 2020–21; the pandemic and the farmers’ protest against the reform-oriented farm laws. The farmers’ protest, which lasted for more than a year, compelled the popular government to repeal the farm laws in November 2021. The epicentre of the farmers’ protest were Punjab, Haryana, and districts in the Northern Upper Ganga Plains (NUGP) in Uttar Pradesh. However, what remains a puzzle is that these are the states or regions of the country with the least number of farmers! The share of the labour force in the agriculture sector in all these three regions of the country is the lowest amongst large states and significantly lower than the national average.

The share of the labour force in the agriculture sector in all these three regions of the country is the lowest amongst large states and significantly lower than the national average.

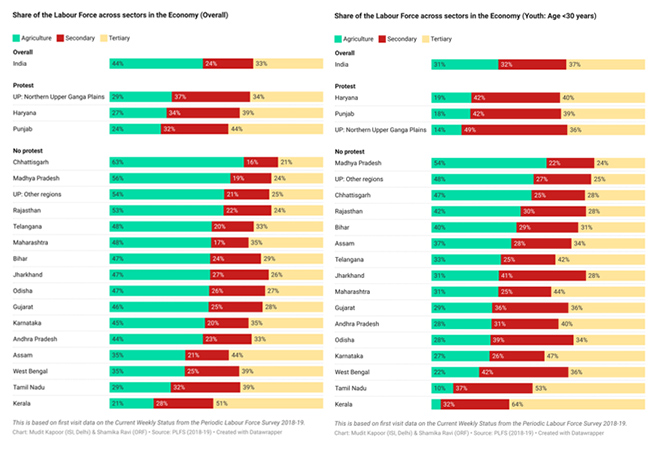

Using the unit-level data on the current weekly status of the Periodic Labour Force Survey for 2018–19, the author finds that the share of agriculture in Punjab was 24 percent, in Haryana, it was 27 percent, and in the Northern Upper Ganga Plains of UP, it was 29 percent, while at the national level, the share of the labour force in the agriculture sector was 44 percent. In terms of the youth (age <30 years) labour force, the analysis reveals that the share of the youth labour force in agriculture in Punjab, Haryana, and NUGP was less than 20 percent, one of the lowest amongst large states and significantly lower than the national share at 31 percent.

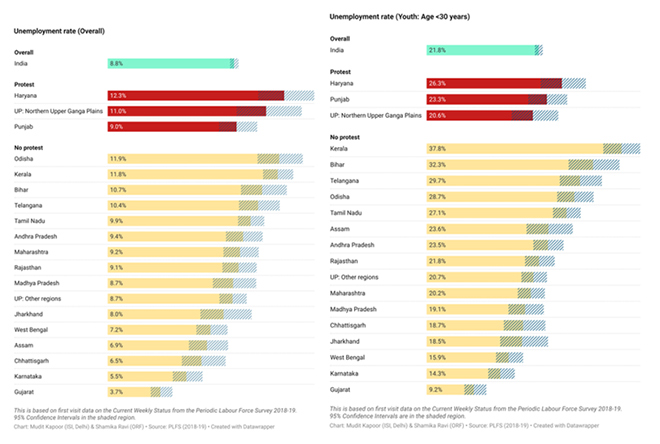

One hypothesis that has been put forth to explain the emergence of the farmers’ protest in these regions is the local levels of unemployment. The data reveals that while Haryana and NUGP had a higher level of unemployment rate, at 12.2 percent and 11 percent, respectively, compared to the national level at 8.8 percent, in Punjab, it was 9 percent, somewhat similar to the national level. More striking, however, is the fact that several large states of India had significantly higher unemployment rates than Punjab but witnessed no mobilisation of protests to the Farm Bills. The unemployment levels in other large states such as Odisha (11.9 percent), Kerala (11.8 percent), Bihar (10.7 percent), Telangana (10.4 percent), Tamil Nadu (9.9 percent), Andhra Pradesh (9.4 percent), Maharashtra (9.2 percent), and Rajasthan (9.1 percent) indicate higher levels of employment distress than Punjab.

Another possible explanation for protests could be youth unemployment. However, when we compare Haryana, Punjab, and NUGP with other large states, we find that youth unemployment rates in these states were significantly lower when compared to large states such as Kerala, Bihar, Telangana, Odisha, and Tamil Nadu. From this, it appears that neither the overall unemployment situation nor youth inactivity levels of these regions can be the distinguishing features for Punjab, Haryana, and the NUGP states to emerge as the epicentre of the farmers’ protest last year.

It remains, therefore, a puzzle that Punjab, Haryana, and NUGP emerged as the sites of prolonged protests in the country—theoretically against the three Farm Acts initiated by the Parliament of India in September 2020. These protests found little to no resonance from the rest of the country which has a significantly higher proportion of the farming population. Naturally, the question that remains is: what powered these protests in India?

This piece was first published on ORF.

Shamika Ravi is a Non-Resident Senior Fellow of the Governance Studies Program at the Brookings Institution Washington D.C. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinion News and Breaking News here

Comments

0 comment