views

Identifying Characteristic Symptoms

Recognize characteristic symptoms (Criterion A). In order to diagnose schizophrenia, a mental health clinician will first look for symptoms in five “domains”: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech and thinking, grossly disorganized or abnormal motor behavior (including catatonia), and negative symptoms (symptoms that reflect a reduction in behavior). You must have at least 2 (or more) of these symptoms. Each must be present for a significant portion of time during a 1-month period (less if the symptoms have been treated). At least 1 of the minimum 2 symptoms must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech.

Consider whether you could be having delusions. Delusions are irrational beliefs that often emerge as a response to a perceived threat that is largely or entirely unconfirmed by other people. Delusions are maintained despite evidence that they are not true. There’s a difference between delusions and suspicions. Many people will occasionally have irrational suspicions, such as believing a co-worker is “out to get them” or that they’re having an “unlucky streak.” The difference is whether these beliefs cause you distress or make it hard to function. For example, if you are so convinced that the government is spying on you that you refuse to leave your house to go to work or school, that is a sign that your belief is causing dysfunction in your life. Delusions may sometimes be bizarre, such as believing you’re an animal or a supernatural being. If you find yourself convinced of something beyond the usual realms of possibility, this could be a sign of delusions (but is certainly not the only possibility).

Think about whether you’re experiencing hallucinations. Hallucinations are sensory experiences that seem real, but are created in your mind. Common hallucinations may be auditory (things you hear), visual (things you see), olfactory (things you smell), or tactile (things you feel, such as the creepy-crawlies on your skin). Hallucinations may affect any of your senses. For example, consider whether you frequently experience the sensation of things crawling over your body. Do you hear voices when no one is around? Do you see things that “shouldn’t” be there, or that no one else sees?

Think about your religious beliefs and cultural norms. Having a belief that others may see as “strange” does not mean you’re having delusions. Similarly, seeing things that others may not is not always a dangerous hallucination. Beliefs can only be judged as “delusional” or dangerous in accordance with local cultural and religious norms. Beliefs and visions are usually only considered signs of psychosis or schizophrenia if they create unwanted or dysfunctional obstacles in your daily life. For example, a belief that wicked actions will be punished by “fate” or “karma” might seem delusional to some cultures but not to others. What count as hallucinations are also related to cultural norms. For example, children in many cultures can experience auditory or visual hallucinations -- such as hearing the voice of a deceased relative -- without being considered psychotic, and without developing psychosis later in life. Highly religious people may be more likely to see or hear some things, such as hearing the voice of their deity or seeing an angel. Many belief systems accept these experiences as genuine and productive, even something to be sought after. Unless the experience distresses or endangers the person or others, these visions are not generally a cause for concern.

Consider whether your speech and thinking are disorganized. Disorganized speech and thinking are basically what they sound like. It may be difficult for you to answer questions effectively or fully. Answers may be tangential, fragmented, or incomplete. In many cases, disorganized speech is accompanied by the inability or unwillingness to sustain eye contact or use non-verbal communication, such as gestures or other body language. You may need the help of others to know whether this is happening. In the most severe cases, speech may be “word salad,” strings of words or ideas that are not related and do not make sense to listeners. As with other symptoms in this section, you must consider “disorganized” speech and thinking must be considered within your own social and cultural context. For example, some religious beliefs hold that individuals will speak in strange or unintelligible language when in contact with a religious figure. Furthermore, narratives are structured very differently across cultures, so stories told by people in one culture may appear “weird” or “disorganized” to an outsider who is unfamiliar with those cultural norms and traditions. Your language is likely to be “disorganized” only if others who are familiar with your religious and cultural norms cannot understand or interpret it (or it occurs in situations in which your language “should” be understandable).

Identify grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior. Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior can manifest in a number of ways. You may feel unfocused, which makes it hard to perform even simple tasks such as washing your hands. You may feel agitated, silly, or excited in unpredictable ways. “Abnormal” motor behavior may be inappropriate, unfocused, excessive, or purposeless. For example, you might frantically wave your hands around or adopt a strange posture. Catatonia is another sign of abnormal motor behavior. In severe cases of schizophrenia, you may remain still and silent for days on end. Catatonic individuals will not respond to external stimuli, such as conversation or even physical prompting, such as touching or poking.

Think about whether you have experienced a loss of function. Negative symptoms are symptoms that show a “decrease” or reduction in “normal” behaviors. For example, a decrease in emotional range or expression would be a “negative symptom.” So would a loss of interest in things you used to enjoy, or a lack of motivation to do things. Negative symptoms may also be cognitive, such as difficulty concentrating. These cognitive symptoms are usually more self-destructive and more obvious to others than the inattentiveness or concentration trouble typically seen in people diagnosed with ADHD. Unlike ADD or ADHD, these cognitive difficulties will occur across most types of situations that you encounter, and they cause significant problems for you in many areas of your life.

Considering Your Life with Others

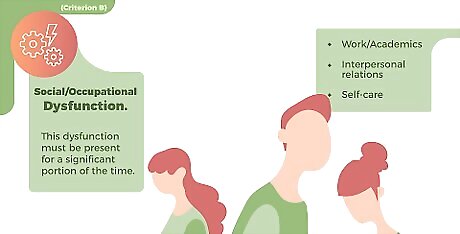

Consider whether your occupation or social life is functioning (Criterion B). The second criterion for a schizophrenia diagnosis is “social/occupational dysfunction.” This dysfunction must be present for a significant portion of the time since you began displaying symptoms. Many conditions can cause dysfunction in your work and social life, so even if you’re experiencing trouble in one or more of these areas, it doesn’t necessarily mean you have schizophrenia. One or more areas of “major” functioning must be impaired: Work/Academics Interpersonal relations Self-care

Think about how you handle your job. One of the criteria for “dysfunction” is whether you are able to fulfill the requirements of your job. If you’re a full-time student, your ability to perform in school could be considered. Consider the following: Do you feel psychologically able to leave the house to go to work or school? Have you had a hard time coming in on time or showing up regularly? Are there parts of your work that you now feel afraid to do? If you are a student, is your academic performance suffering?

Reflect on your relationships with other people. This should be considered in light of what is normal for you. If you’ve always been a reserved person, not wanting to socialize isn’t necessarily a sign of dysfunction. However, if you’ve noticed your behaviors and motivations change to things that aren’t “normal” for you, this could be something to speak with a mental health professional about. Do you enjoy the same relationships you used to? Do you enjoy socializing in the way you used to? Do you feel like talking with others significantly less than you used to? Do you feel afraid or intensely worried about interacting with others? Do you feel like you're being persecuted by others, or that others have ulterior motives toward you?

Think about your self-care behaviors. “Self-care” refers to your ability to take care of yourself and remain healthy and functional. This should also be judged within the realm of “normal for you.” So, for example, if you usually work out 2-3 times per week but haven’t felt like going in 3 months, this could be a sign of disturbance. The following behaviors are also signs of lapsed self-care: You have started or increased abusing substances such as alcohol or drugs You don’t sleep well, or your sleep cycle varies widely (e.g., 2 hours one night, 14 hours the next, etc.) You don’t “feel” as much, or you feel “flat” Your hygiene has gotten worse You don’t take care of your living space

Thinking About Other Possibilities

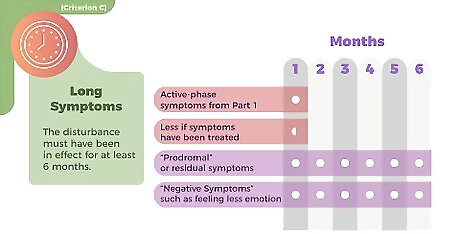

Consider for how long symptoms have been appearing (Criterion C). To diagnose schizophrenia, a mental health professional will ask you how long the disturbances and symptoms have been going on. To qualify for a diagnosis of schizophrenia, the disturbance must have been in effect for at least 6 months. This period must include at least 1 month of “active-phase” symptoms from Part 1 (Criterion A), although the 1-month requirement may be less if symptoms have been treated. This 6-month period may also include periods of “prodromal” or residual symptoms. During these periods, the symptoms may be less extreme (i.e., “attenuated”) or you may experience only “negative symptoms” such as feeling less emotion or not wanting to do anything.

Rule out other possible culprit illnesses (Criterion D). Schizoaffective disorder and depressive or bipolar disorder with psychotic features can cause symptoms very similar to some of those in schizophrenia. Other illnesses or physical traumas, such as strokes and tumors, can cause psychotic symptoms. This is why it is crucial to seek help from a trained mental health clinician. You cannot make these distinctions on your own. Your clinician will ask if you have had major depressive or manic episodes at the same time as your “active-phase” symptoms. A major depressive episode involves at least one of the following for a period of at least 2 weeks: depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure in things you used to enjoy. It will also include other regular or near-constant symptoms in that time frame, such as significant weight changes, disruption in sleeping patterns, fatigue, agitation or slowing down, feelings of guilt or worthlessness, trouble concentrating and thinking, or recurrent thoughts about death. A trained mental health professional will help you determine whether you have experienced a major depressive episode. A manic episode is a distinct period of time (usually at least 1 week) when you experience an abnormally elevated, irritated, or expansive mood. You will also display at least three other symptoms, such as decreased need for sleep, inflated ideas of yourself, flighty or scattered thoughts, distractibility, increased involvement in goal-directed activities, or an excessive involvement in pleasurable activities, especially those with a high risk or potential for negative consequences. A trained mental health professional will help you determine whether you have experienced a manic episode. You will also be asked how long these mood episodes lasted during your “active-phase” symptoms. If your mood episodes were brief in comparison to how long the active and residual periods lasted, this may be a sign of schizophrenia.

Rule out substance use (Criterion E). Substance use, such as drugs or alcohol, can cause symptoms similar to those in schizophrenia. When diagnosing you, your clinician will make sure that the disturbances and symptoms you’re experiencing are not because of the “direct physiological effects” of a substance, such as an illegal drug or medication. Even legal, prescribed medications can cause side effects such as hallucinations. It’s important for a trained clinician to diagnose you so that s/he can distinguish between side effects from a substance and symptoms of an illness. Substance use disorders (commonly known as “substance abuse”) commonly co-occur with schizophrenia. Many people suffering from schizophrenia may attempt to “self-medicate” their symptoms with medication, alcohol, and drugs. Your mental health professional will help you determine if you have a substance use disorder.

Consider the relationship to Global Developmental Delay or Autism Spectrum Disorder. This is another element that must be handled by a trained clinician. Global Developmental Delay or Autism Spectrum Disorder may cause some symptoms that are similar to those in schizophrenia. If there is a history of autism spectrum disorder or other communication disorders that begin in childhood, a diagnosis of schizophrenia will only be made if there are prominent delusions or hallucinations present.

Understand that these criteria do not “guarantee” that you have schizophrenia. The criteria for schizophrenia and many other psychiatric diagnoses are what as known as polythetic. This means that there are many ways of interpreting the symptoms, and different ways the symptoms may combine and appear to others. Diagnosing schizophrenia can be difficult even for trained professionals. It is also possible, as mentioned before, that your symptoms could be the result of another trauma, illness, or disorder. You must seek professional medical and mental health help to properly diagnose any disorder or disease. Cultural norms and local and personal idiosyncrasies in thought and speech can affect whether your behavior appears “normal” to others.

Taking Actions

Ask your friends and family for help. It can be hard to identify some things, such as delusions, in yourself. Ask your family and friends to help you figure out whether you are displaying these symptoms.

Keep a journal. Write down when you think you may be having hallucinations or other symptoms. Keep track of what happened just before or during these episodes. This will help you figure out how commonly these things occur. It will also help when you consult a professional for diagnosis.

Take notice of unusual behaviors. Schizophrenia, especially in teenagers, can creep up slowly over a period of 6-9 months. If you notice that you're behaving differently and don't know why, talk with a mental health professional. Don’t just “write off” different behaviors as nothing, especially if they are very unusual for you or they’re causing you distress or dysfunction. These changes are signs that something is wrong. That something may not be schizophrenia, but it's important to consider.

Take a screening test. An online test can't tell you if you have schizophrenia. Only a trained clinician can make an accurate diagnosis after tests, examinations, and interviews with you. However, a trustworthy screening quiz can help you figure out what symptoms you may have and whether they are likely to suggest schizophrenia. The Counselling Resource Mental Health Library has a free version of the STEPI (Schizophrenia Test and Early Psychosis Indicator) on their website. Psych Central has an online screening test as well.

Talk with a professional. If you're worried that you might have schizophrenia, talk with your physician or therapist. While they do not usually have the resources to diagnose schizophrenia, a general practitioner or therapist can help you understand more about what schizophrenia is and whether you should see a psychiatrist. Your physician can also help you rule out other causes of symptoms, such as injury or illness.

Knowing Who’s At Risk

Understand that the causes of schizophrenia are still being investigated. While researchers have identified some correlations between certain factors and the development or triggering of schizophrenia, the exact cause of schizophrenia is still unknown. Discuss your family history and medical background with your doctor or mental health provider.

Consider whether you have relatives with schizophrenia or similar disorders. Schizophrenia is at least partially genetic. Your risk for developing schizophrenia is about 10% higher if you have at least one “first-degree” family member (e.g., parent, sibling) with the disorder. If you have an identical twin with schizophrenia, or if both of your parents have been diagnosed with schizophrenia, your risk of developing it yourself is more like 40-65%. However, about 60% of people who are diagnosed with schizophrenia do not have close relatives who have schizophrenia. If another family member -- or you -- has another disorder similar to schizophrenia, such as a delusional disorder, you may be at higher risk for developing schizophrenia.

Determine if you were exposed to certain things while in the womb. Infants who are exposed to viruses, toxins, or malnutrition while in the womb may be more likely to develop schizophrenia. This is especially true if the exposure happened in the first and second trimesters. Infants who experience a lack of oxygen during birth may also be more likely to develop schizophrenia. Infants who are born during a time of famine are more than twice as likely to develop schizophrenia. This may be because malnourished mothers cannot get enough nutrients during their pregnancy.

Think about your father’s age. Some studies have shown a correlation between the age of the father and the risk for developing schizophrenia. One study showed that children whose fathers who were 50 years old or older when they were born were 3 times as likely to develop schizophrenia as those whose fathers were 25 years old or younger. It is thought that this may be because the older the father is, the more likely his sperm is to develop genetic mutations.

Comments

0 comment