views

ORLANDO, Fla. Bob Garick was looking forward to being a field supervisor during the door-knocking phase of the 2020 census, but as the number of new coronavirus cases in Florida shot up last month, he changed his mind.

With widespread home visits for the 2020 census set to begin next week, the Census Bureau is losing workers like Garick to pandemic fears. The attrition could complicate the bureau’s plans to ramp up efforts to reach the hardest to count communities, including minorities and immigrants, on a shortened schedule.

Before, I thought it was my civic duty, to do my part, but now its like the health concerns are too great, said Garick, 54, a software development director who is between jobs.

Door-knockers started heading out last month in six areas of the country in a test-run of the most labor-intensive part of the 2020 census, and their ranks have increased with each passing week as more locations were added. But next week, the full army of 500,000 census-takers will be in the field for the first time, knocking on the doors of more than a third of U.S. households that haven’t yet responded to the once-a-decade head count.

The census helps determine how $1.5 trillion in federal spending is distributed and how many congressional seats each state gets.

Bureau officials acknowledge that they’ve had door-knockers, also known as enumerators, come to training but then not show up for work. The door-knockers wear cloth face masks and come equipped with hand sanitizer and cellphones.

We are seeing folks who are a little hesitant because of the COVID environment, Deborah Stempowski, the Census Bureaus assistant director for decennial programs, told a conference of data users last week.

Other non-COVID factors are also playing a role. Some enumerators are uncomfortable with the technology, as iPhones have replaced the clipboards of censuses past. The pandemic has forced training to be held mostly online and theres less in-person interaction with supervisors should enumerators need help, Stempowski said.

Concerns about attracting door-knockers forced the Census Bureau to raise its hourly wage: Enumerators in the highest-paying cities can now earn $30 an hour. Based on historical trends, the Census Bureau’s planning models assume 20% of door-knockers won’t show up for training, but the bureau’s media office said it’s too early to say what attrition rates are this year.

A census taker in Orlando who also was a door-knocker for the 2010 census says the training this time has been quite different. She asked not to be identified for fear of losing her job.

A decade ago, she had 40 hours of training with other census takers in a class where they practiced face-to-face, helping each other develop techniques to persuade reluctant people to answer the census questionnaire.

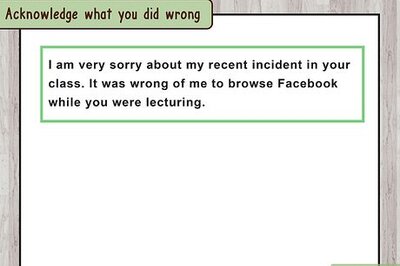

“We had a lot of practice with each other, she said. A lot of people whose doors you knock on are reluctant to talk to you, and some people dont want to give any information to the government. If theyve never done it before, its hard to persuade and convince people.

For the 2020 census, her training has been about half that time and primarily online because of the pandemic, though she was required to have an in-person meeting with her supervisor.

Census Bureau director Steven Dillingham said in prepared remarks to a House committee last week that the bureau has 3 million applicants available, and that more than 900,000 job offers have been accepted. But he acknowledged that the number of door-knockers deployed to the field in the test-run was lower than expected, and that offices used for fingerprinting and meeting with census takers have had to close at the last minute because of coronavirus conditions.

This large number of offers is needed to cover attrition, Dillingham said. Unlike prior censuses, concern with the pandemic is estimated to increase the number of no shows to training sessions, as well as the number of employees who complete training but decline to show up for work.

The Census Bureau also is recruiting more workers in specific areas of the country, and regional offices are training replacement enumerators on an ongoing basis, he said.

The statistical agency is dealing with a shorter schedule for door-knocking than it anticipated earlier this summer. Facing pandemic-related delays in April, the Census Bureau had asked Congress for delays in handing over data used for redrawing congressional and legislative districts, and it pushed back wrapping up its data collection through door-knocking or self-responses from the end of July to the end of October.

The request passed the Democratic-controlled House, but it’s not going anywhere in the Republican-controlled Senate. The inaction coincides with a memorandum President Donald Trump issued last month to try to exclude people living in the U.S. illegally from being part of the process for redrawing congressional districts.

The lack of action is forcing the Census Bureau to turn in numbers used for redrawing congressional districts by the end of the year, instead of by the end of next April as requested. To meet the year-end deadline, the agency announced this week it would finish data collection at the end of September instead of the end of October. Some census officials had previously said they would be unable to meet the end-of-the-year deadline.

When Garick told his supervisors that he was withdrawing from the job, they seemed unfazed, he said. It seemed as if they had heard the same thing many times before.

I’m a little disappointed that I’m not going to do it, but it didn’t seem like a wise move on my part,” Garick said.

–

Follow Mike Schneider on Twitter at https://twitter.com/MikeSchneiderAP

Disclaimer: This post has been auto-published from an agency feed without any modifications to the text and has not been reviewed by an editor

Comments

0 comment