views

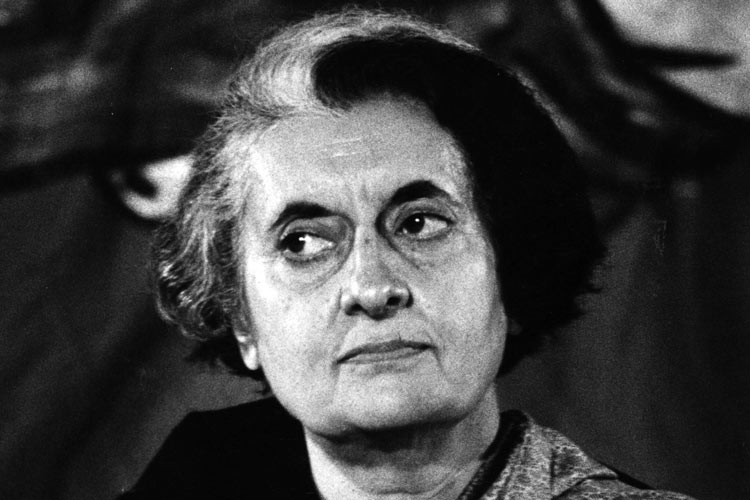

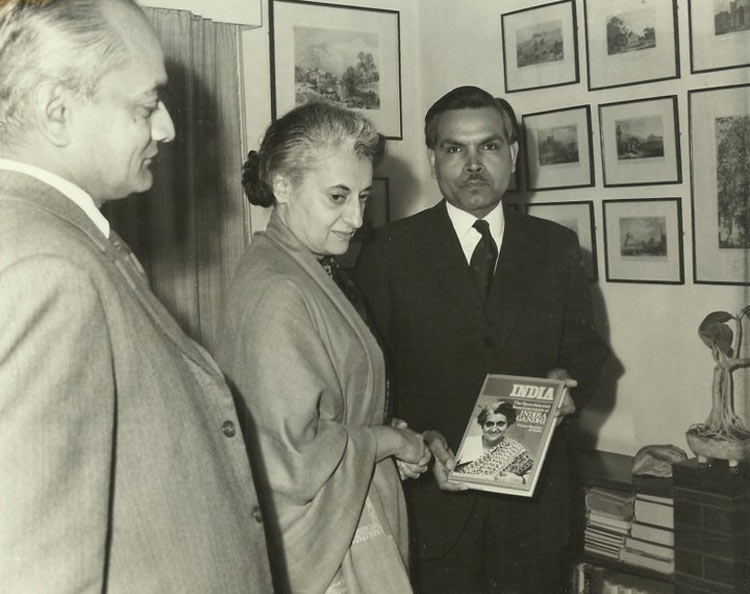

( Prime Minister Indira Gandhi imposed Emergency on June 25, 1975. Her decision had shocked the entire World. Civil liberties were suspended and lakhs of people were sent to jail across India. This article was originally published on June 25, 2015. News18 is republishing the article on the 43rd anniversary of Emergency. Technocrat Ravi Visvesvaraya Sharada Prasad shares his personal memories of the Emergency days in this article. His father, the legendary HY Sharada Prasad, was Information Advisor to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi till her death. He was one of the closest advisors to her and her son Rajiv Gandhi. Readers get a ringside view of what happened behind the scenes before and during the Emergency)

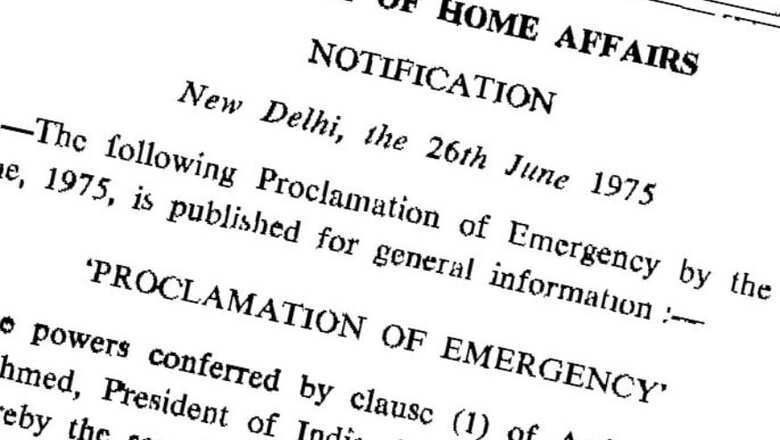

Immediately after President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed signed the proclamation of the Emergency, Jayaprakash Narayan was arrested from the Rouse Avenue home of my maternal uncle, KS Radhakrishna, head of the Gandhi Peace Foundation. Earlier that evening, JP had addressed a massive rally at Ram Lila Maidan, where he exhorted the police and armed forces to not obey orders which they considered wrong.

Many decades later, my maternal uncle described the events of that day. Many of JP's colleagues and aides were shocked and aghast at his calling upon the armed forces and police to disobey orders. Most vociferous was the strict disciplinarian Morarji Desai, who was a stickler for law and order, rules and regulations. There were heated arguments between Morarji and JP. Subramanian Swamy mediated between the two, and calmed them down.

"I told you not to take an extreme stance. Now that you have pushed Indira Gandhi into a corner, she will retaliate harshly. Even now, give her a face saving way of coming to a settlement with us," Biju Patnaik told JP.

After returning from Ramlila Maidan, JP, Morarji Desai, and Subramaniam Swamy had dinner with my maternal uncle at his house on Rouse Avenue. Subramanian Swamy noticed Intelligence Bureau officials in plain clothes outside and voiced his apprehensions that they would all be arrested.

Swamy wondered if Indira Gandhi would declare martial law. Both JP and Morarji Desai replied that Nehru's daughter would never do such a thing. Swamy was not convinced. He escaped and went underground, resurfacing some months later to make a dramatic speech in Parliament, and escape again. Morarji Desai left the dinner early and returned to his residence. Shortly afterwards, one of their sympathisers in the administration phoned my uncle to tell him that JP and others would be arrested soon. A short while later, Maxwell Pereira came to my maternal uncle's home to arrest JP and him.

Chandrashekhar was arrested from Rivoli theatre in Connaught Place where he was watching a movie with BP Koirala. The police officer took Chandrashekhar to a nearby phone booth and told him to call all his friends all over the country to warn them of their imminent arrest and that they should escape immediately.

George Fernandes escaped to Orissa (now Odisha), grew a beard and disguised himself as a Sikh, taking the name Khushwant Singh, the first Sikh he could think of. PN Haksar, PN Dhar, BN Tandon, and my father were especially concerned over amendments to the constitution and the undermining of the judiciary, which was principally done on the advice of Siddhartha Shankar Ray. The then Law Minister HR Gokhale had his qualms but acquiesced in the subversion of the judiciary.

While hearing Indira Gandhi's election appeal, Justice Mirza Hameedullah Beg asked the Solicitor General Lal Narayan Sinha if he knew of any other instance where the Executive Branch of Government had arrogated to itself the powers of the judicial and legislative branches. After thinking for a while, LN Sinha replied: "The Court of Jahangir". Justice Beg retorted that Indira Gandhi did not have the sense of justice and fair play of Jahangir, and asked Sinha if she wanted to regress the nation back to the 17th century. The Prime Minister's House and Vidya Charan Shukla exerted great pressure on newspapers to not carry the above exchange, nor indeed any of the arguments of Nani Palkhivala.

Ironically, Justice Mirza Hameedullah Beg soon delivered a highly favourable judgement in Indira Gandhi's election appeal, and was rewarded by being made the Chief Justice, superseding Justice HR Khanna. Indira Gandhi asked my father to help draft her speech for the Congress Party Session at Chandigarh in December 1975. My father retorted that this was party work rather than government work, and that he would rather resign. She heatedly replied that she intended to announce important government policies, to which my father replied that it was a Congress party function and not a government function. My father added that government policies were to be announced on the floor of Parliament, and not at party sessions. Heated words were exchanged and my father offered his resignation. PN Dhar told the prime minister that she was overstepping the line. She backed down and apologised to my father, but not before remarking that he had been brainwashed by PN Haksar about due processes.

Why Indira Gandhi lifted the Emergency in January 1977 and called for fresh elections to be held in March 1977 remains a mystery to this day. The popular notion is that intelligence agencies gave her reports that she would win the elections easily. But this is not true at all. She told my father and other officials of her Secretariat in January 1977: "I am lifting the Emergency and calling for elections. I know I will probably lose, but I must do this."

PN Dhar had remarked a few months earlier that Indira Gandhi herself had begun to turn against the Emergency. She had remarked to Michael Mackintosh Foot that she was unhappy about the Emergency and would lift it as soon as the situation improved. Then when Jagjivan Ram and Hemavati Nandan Bahuguna defected, she told my father,"It is all over now. I am sure to lose the elections."

One thing which always puzzled my father was that how did someone as astute and shrewd as Indira Gandhi make the elementary political blunder of imprisoning various opposition leaders together and permitting them to interact with each other. This allowed them to unite together against her.

Professor PN Dhar was to write: "How then do we assess the phenomenon of the Emergency? Was it an aggravation of the tendency to disregard the law which had become a part of Indian political culture? In which case, was it the logical climax of this culture? Or was it an aberration caused by Indira Gandhi's personality, twisted by her sense of insecurity? Whatever the final assessment that historians may make about Indira Gandhi, one conclusion is clear from the events preceding and following the Emergency declaration: it was not a contest between a revolutionary leader leading the hosts towards a new social and political order and a wily politician anxious to impose her personal dictatorship on the country. The actual outcome, on both sides of the barricades, was much less spectacular. JP proved an ineffectual revolutionary and Indira Gandhi a half-hearted dictator."

Lal Krishna Advani raised a controversy by saying that it was possible for Emergency like situations to arise again. Professor PN Dhar and my father had analysed these situations extensively, and were of the conclusion that governments really had no means other than repression to deal with Satyagraha and Civil Disobedience. As my father had written in Realpolitik magazine in March 2006:

"The trouble is with the unresolved issue of the place of Satyagraha in a parliamentary democracy. All governments, whether colonial or autonomous, react the same way when their existence or legitimacy is questioned. The British arrested Gandhi and Nehru, and Nehru's daughter in turn arrested a person identified with Gandhi and Nehru."

Indeed the founding fathers of our parliamentary democracy had recognised the dangers of continuing with methods of Satyagraha and Civil Disobedience in an independent India.

Dr BR Ambedkar stated in the Constituent Assembly on November 25, 1949.

"It is quite possible for this newborn democracy to retain its form but to give place to dictatorship in fact. If there is a landslide, the danger of the second possibility becoming actuality is much greater…If we wish to maintain democracy not merely in form, but also in fact, what must we do? The first thing in my judgment we must do is to hold fast to constitutional methods of achieving our social and economic objectives. It means we must abandon the bloody methods of revolution. It means that we must abandon the method of civil disobedience, non-cooperation and satyagraha. When there was no way left for constitutional methods for achieving economic and social objectives, there was a great deal of justification for unconstitutional methods. But where constitutional methods are open, there can be no justification for these unconstitutional methods. These methods are nothing but the Grammar of Anarchy and the sooner they are abandoned, the better for us…"

Second, there is evidence that Mahatma Gandhi had himself come around to accept that Satyagraha should not be used in a democracy. I quote from the reminiscences of the famous lawyer Purshottam Trikamdas, who was a close aide of Mahatma Gandhi (Incidentally, Purshottam Trikamdas was my mother's boss at the law firm of Kanga and Co, and it was Mahatma Gandhi himself who had recommended my mother to Purshottam Trikamdas). Trikamdas and Mahatma Gandhi had several heated debates and differences about the political future of India after Independence.

From Trikamdas' reminiscences:

"After Gandhiji was released and we had the Poona Conference over which MS Aney, who was then the Acting President of the Congress, presided, I tried to meet Gandhiji but his nephew prevented me from meeting him because he knew my views to which I shall refer presently. Anyway, Aney was good enough to invite me to that meeting of Congressmen….

"I went up to Gandhiji at the end of the meeting and I said, 'I am trying to meet you and your nephew is preventing me from meeting you.' He said, 'No, no, nobody can do that. You come and see me.' I would like to mention that in my speech I had said, 'I do not know what card Gandhiji had up his sleeve.' I was amused to find that some people thought this to be disrespectful because Gandhiji never played cards.

"When I went to him the next day, he showed me the letter which he had prepared for being dispatched to the Viceroy. In the letter, he had mentioned that Satyagraha must be recognised as a constitutional right. So, I said to Gandhiji with utmost respect, 'Several views have been expressed for framing our Constitution. Tomorrow, when India is free, would you say that Satyagraha is a constitutional right and write it into the Constitution. And, if we do, what does it mean? It means that anybody can break the law with impunity and nothing could be done. Actually, it would be contrary to your own ideas. Satyagraha, you say, means disobeying authority and facing the consequences. Now, if Satyagraha is a constitutional right and it is permitted, what are the consequences to face?"

It would be said to the credit of the great man that he started thinking and he said, 'There is something in what you say.'

Next day, he sent for me and said, 'You are right. I have decided not to send that letter.' Such was the greatness of the man; he always kept an open mind. After he had actually drafted the letter and finalised it, he said, 'I am not sending it.'"

(Ravi Visvesvaraya Sharada Prasad, an alumnus of Carnegie Mellon University and Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, is a consultant in telecommunications and information technology. He has four masters degrees in engineering and science. Views are personal)

Comments

0 comment