views

The notion that the law has long arms is deeply embedded in popular culture and legal theory. However, the normative claims of nobody being beyond the reach of the law’s arms would seem like empty rhetoric if one glances at the uphill task of extraditing fugitives.

Extradition of fugitives involves the intersection of international law, domestic law, politics and diplomacy. What makes extradition an intricate process is the fact it that often involves a conflict between the interests of two or more sovereign states. On the one hand, the government of a country where the crime occurred may assert its power to prosecute and punish the fugitive so as to enforce the law of the land and deliver justice to the victim. On the other hand, the government of the country where the fugitive resides may be obligated under domestic law or international law not to extradite a fugitive so as to prevent persecution, violation of human rights etc. after the extradition.

This being the case, it is hardly surprising that India has managed to extradite less than 75 fugitives since 2002. India is still looking for more than 300 fugitives. Though India has entered into extradition treaties with 47 countries and has extradition arrangements with 11 countries, extraditing fugitives is a long-drawn process which requires the Indian agencies to coordinate with foreign governments, foreign courts and even the INTERPOL if necessary.

A serious impediment to extraditing fugitives to India is the poor jail conditions. Indian jails are notorious for being overcrowded. The occupancy rate of some of the jails is as high as 179%. To make matters worse, the number of custodial deaths is high and reports suggest that abysmal medical facilities and poor hygiene are the main reasons for these deaths.

Although India and the UK have entered into an extradition treaty in 1993, the condition of the Indian jails has forced the UK courts not to readily extradite fugitives. This is because detention in a crowded prison with abysmal medical facilities is considered as a breach of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the Human Rights Act, 1988 and the Extradition Act, 2003. Raymond Varley, a British national who was accused of sexually abusing more than 150 children in Goa, resisted extradition to India by claiming that the prison conditions in Goa posed a threat to his life.

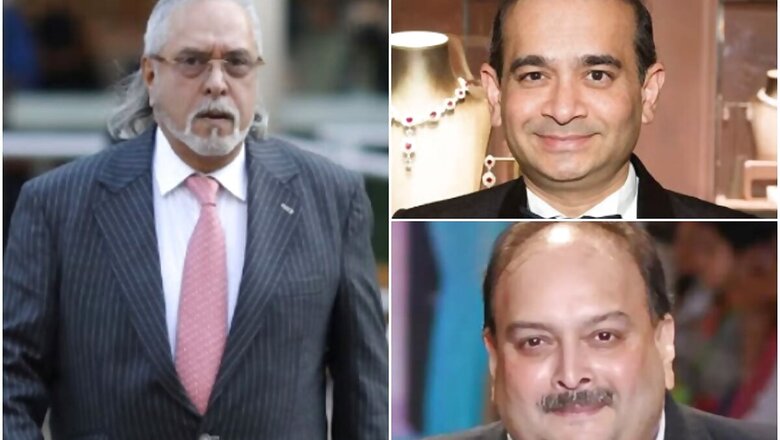

Two experts from the UK were allowed to inspect the prison in Goa. This delayed the proceedings and eventually, the court did not allow him to be extradited as he claimed to have dementia. Even Vijay Mallya and Nirav Modi urged the UK courts not to allow their extradition as the prison conditions in India would violate their human rights. The Government of India had to refurbish the Arthur Road Jail to assure the UK courts that they would not be detained in inhumane conditions. Furthermore, the courts were assured that they would enjoy certain facilities that are not readily available to other inmates. These onerous requirements and judicial proceedings have delayed their extradition and it could be further delayed until they exhaust other remedies such as seeking asylum.

Fugitives have also resisted extradition requests from India by claiming that they would be punished without a fair trial. Nirav Modi and Vijay Mallya contended before the courts that they were victims of a media trial and that the Indian government was persecuting them using various agencies. Nirav Modi went a step ahead and claimed that the Indian judiciary was no longer independent. Justice Katju, a retired Supreme Court judge, testified in his favour as an expert witness. Though this contention was rejected by the Westminster Magistrates’ Court, Nirav Modi is free to challenge the decision before the appellate courts. Fugitives like Nadeem Saifi managed to avoid extradition by convincing the court that the “accusation was not made in good faith and in the interests of justice”, which is recognised in the India-UK Extradition Treaty, as a ground to avoid extradition.

Some of the successful extraditions to India include those of gangsters Abu Salem and Ravi Pujari. Both these extraditions involved coordination with the INTERPOL to secure their presence. India had to assure Portugal that Abu Salem would not be sentenced to death as Portugal was obligated under the ECHR not to extradite a fugitive who could eventually be executed. Ravi Pujari’s extradition from Senegal involved relentless efforts by the Indian agencies as he delayed the proceedings by contending that he was not the person being sought by India. His extradition was delayed as he was facing trial in a cheating case before a court in Senegal.

Mehul Choksi, who is currently in the news for being detained in Dominica, had strategically fled to Antigua to avoid extradition. He acquired citizenship through the investment route and thereafter approached an Antiguan court and obtained a temporary stay on his extradition. While India has approached the Dominican court seeking his custody, his counsel has argued that he can only be deported to Antigua as he is an Antiguan citizen.

When caught in a country which is neither the home country nor the country where the crime was committed, it is rather common for fugitives to urge the authorities to deport them to the home country. For instance, Raymond Varley was arrested in Thailand but was deported to his home country Britain, and not India. If the same happens with Mehul Choksi, his extradition could get delayed as judicial proceedings are pending in Antigua.

It is pertinent to understand that diplomacy alone will not improve India’s track record of extraditing fugitives. Diplomacy may remove barriers erected by the foreign governments but has a minimal role before the foreign courts that hear extradition pleas.

The focus ought to be on preventing offenders from fleeing the country by exploiting the laxity of the Indian agencies. Furthermore, selectively refurbishing prisons to facilitate extradition is an affront to constitutional values. Decongesting and refurbishing prisons ought to be ends in themselves and not merely the means to extradite fugitives. It is ironic that criminals who flee the country and display scant respect for the law may eventually enjoy special facilities in prisons while those who chose not to outsmart the state, languish in inhumane conditions.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here.

Comments

0 comment