views

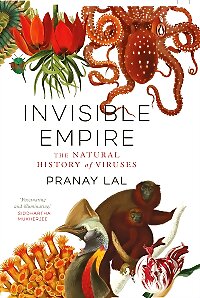

The word ‘virus’ evokes fear in us, and since the pandemic our condemnation for the microbial world has become even more entrenched. SARS-CoV-2 is among our most recent encounters with the virosphere. A few generations ago, a population of viruses acquired changes in their genes from an animal host, which provided them with the ability to infect humans. This enabled this newly emerged virus to readily attach to a receptor in our cells, which we call ACE2 (or Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; angiotensin is a protein hormone that causes blood vessels to become narrower and is vital for maintaining blood pressure and fluid balance in the body). ACE2 is found in several mammals, and in us they are primarily present in our lungs and guts. When virologists teased open the RNA of SARS-CoV-2, they found that it carried genes that are found in a variety of animals—in other viruses, bacteria, slugs, small mammals, and perhaps unsurprisingly therefore, nearly 94% of its genes are found in humans too. But a handful of its genes are completely unique to it and their functions are yet unknown. This makes it difficult to predict how SARS-CoV-2 will behave once it enters our bodies.

Our technological progress, our ability to acquire instant (albeit often ephemeral) gratification, has lulled us into believing that we possess enough power to subdue and manipulate nature. We choose which relationships we want to foster and which we will cull and sever, and try to make nature serve us selectively and indefinitely. This kind of brinkmanship makes us feel that we can control nature, but as we have slowly begun to realise, this control is delusional. It is time we stopped looking at nature as a pliable variable or as an entity that impedes ‘progress’, or a tool of one-upmanship. I say this now because there are controversies about the origin of SARS-CoV-2—did the virus jump from an animal to unsuspecting buyers in a wet market or did it leak from a lab? Was it designed as a bioweapon? For me, these questions are relevant only if we have the courage to take corrective action and hold institutions or governments accountable. Otherwise this is a futile blame game best left to politicians and diplomats. The origin of the virus could be significant for science if it helps us determine the virus’s lineage and identify its potential hosts which will help us plan future strategies.

Regardless of how it originated, SARS-CoV-2 reminds us that provoking nature beyond a point can lead to unimagined and irreversible consequences. Anyone who understands nature’s processes knows that soils, mud, detritus, mulch, sand, gravel, grit and rock are crucial pieces in the climate change story, as are the ocean currents, wind circulation, the shapes and size of land masses and, of course, life forms—especially microbes, the principal primary energy producers on Earth that regulate the bulk of Earth’s carbon-oxygen cycle. When all these small pieces come together, they power Earth’s engines. This engine is an enormous, planetary-scale, biogeochemical reactor—but it starts from small things. Like viruses and microbes.

Viruses cause a billion infections a second (or 1029 infections a day). They tinker and shuffle genes at great speed, creating possibilities of making new varieties of life. Like geological processes, which create and shape diverse landscapes, viruses and microbes enable speciation and finds ways to fit new entities within ecosystems that their predecessors have shaped. Each ecosystem—a tropical forest, a vast grassland, a small pool or even microbiomes within every individual creature—has been thousands and even millions of years in the making, and is constantly evolving. These unceasing interactions of life forms in an ecosystem rest on the bedrock of microbial and mineral activity. Microbes are not only engines of evolution but they also digest, produce, process, ferment, break down, recycle, reformulate and synthesise chemicals faster and more efficiently than any human-made machine. A deeper appreciation of the microbial world is critical to mitigating climate change and managing future pandemics effectively.

Every microbiome is distinct and is linked with our immediate environment. The microbiomes inside us are thriving and virtually every ounce of all our body fluids, tissues and organs of our bodies have distinct viruses and myriads of microbes that usually do more good to us than harm. Even parts of our bodies that were once considered sterile—our brain and spinal fluids, heart or kidneys—harbour specific viruses within them. If any ecosystem suffers injury or repeated insults, it cannot be restored to its original state even with the most advanced scientific effort. Like any other pathogen that established itself as a persistent disease, SARS-CoV-2, too, was a chance occurrence. We enabled its crossover through destruction of habitats and trade in wildlife. And once the outbreak occurred, mass movements of people, weak and bigoted science, the fragmented response by agencies, a blunderbuss of regulations and distrust between states, sustained the spread and evolution of the novel virus.

Using a global database of the virus’s RNA collected from across the world, virologists have been able to monitor small mutations of the virus’s 29,903-letter RNA code (our DNA has nearly 3 billion, gut-dweller E. coli genome has 4.6 million). Two COVID-causing viruses isolated from patients anywhere in the world differ by an average of just ten RNA letters out of 29,903. With such slight changes, the virus becomes either more infective or more transmissible and several variants also peter out into oblivion. A couple of mutations makes a variant, and it takes an accumulation of several mutations to create a distinct species. This usually occurs when the virus passes through several different populations and encounters new immunological and other challenges (drugs used during treatment, for example).

Variants of SARS-CoV-2 may be a long way away from becoming distinct species. Or not, since dogs, cats, tigers, minks and other animals are getting infected by interacting with humans. What we do know is that as it sets off on its uncharted journey, SARS-CoV-2 is opening up possibilities for other microbes to invade and colonise our microbiomes, and thus, change their fate, as well as ours. For SARS-CoV-2, the pandemic is not just a one-off chance but an evolutionary moment. The effects of the pandemic will not wear off any time soon. The virus has triggered massive changes starting with our bodies and encompassing the body politic and these will probably stay with us for a very long time. Perhaps forever.

The pandemic has once again highlighted how little we know about the microbial world and how difficult it is for human technology to keep up with it. There are many new viruses being recorded each year. Since 2014, at least one new virus has been added to the list of known viruses that reside in our lungs, and in the last count, at least 20 of them have been found living in just the respiratory tract. We cannot outnumber or even outmatch viruses. We must find ways to make peace with microbes (and viruses, in particular). Since we are living in a time when we are trying to set right past misdemeanours and political gaffes, we perhaps also need to begin building some appreciation for the microbe-kind and recognise their contributions. It comes as a surprise to me that even the most erudite scientists, popular science writers, broadcasters, doctors and public health experts, casually use labels like ‘bug’, ‘critter’, ‘pest’, ‘intruder’, among others, for microbes and the minutiae. Perhaps we should begin by according microbes the right honorific. If we continue to speak of microbes and viruses using the lexicon of war, then it is a war we have already lost. It is ironic that we are supposedly at war with this invisible force, which can cause disruption, but which also binds all life.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment