views

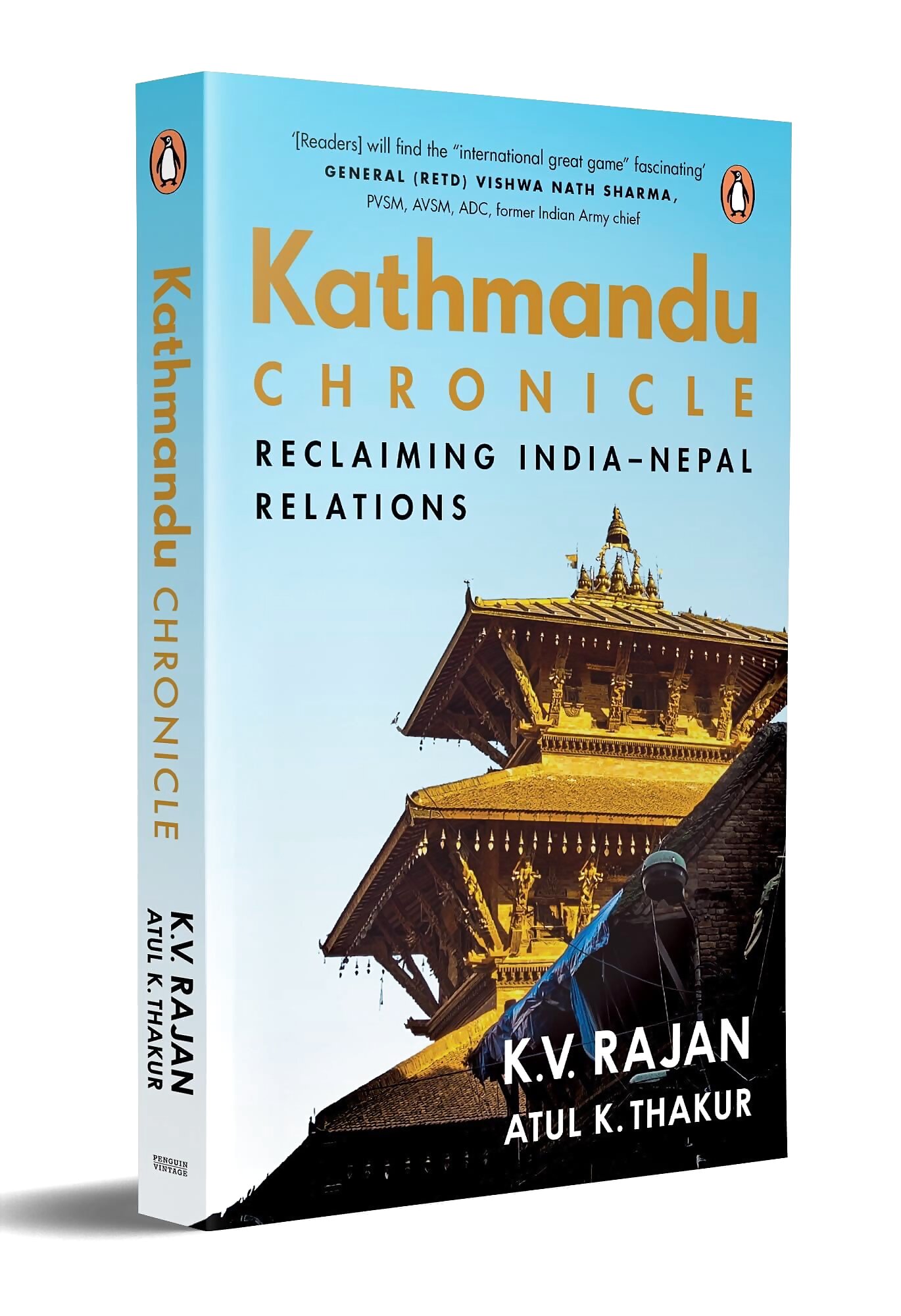

KV Rajan and Atul K Thakur have produced Kathmandu Chronicle: Reclaiming India-Nepal Relations. This book offers a unique perspective, meshing the recollections and reflections of a seasoned ambassador, KV Rajan, with the real-life macroeconomic insights of policy professional, Atul K Thakur. Rajan’s tenure in Nepal spanned five and a half critical years, from the spring of 1995 to March 31, 2001. This period witnessed the commencement of Nepal’s democratisation, as the nation transitioned from an absolute to a constitutional monarchy. However, this period also saw the tragic foreshadowing of the monarchy’s eventual end, catalysed by the mysterious massacre in Narayanhiti Durbar, that wiped out in June 2001, all but one claimant to the crown.

Rajan had proven himself so indispensable to the establishment that, even after his retirement, he was asked to continue as an advisor on Nepal. His expertise was so highly valued that even after he stepped down from advising the Indian Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, Nepal continued to seek his counsel, prompting frequent trips back to Kathmandu. While individuals of Rajan’s generation are becoming fewer in Nepal, younger entrepreneurs like co-author Atul K Thakur are emerging, representing an “aspirational new Nepal”.

Thakur is married into Janakpur: so is a better half of Nepal. He has edited former Nepal Finance Minister Madhukar Rana’s book, ‘An Alternative Development Paradigm for Nepal’, and is actively involved in India-Nepal economic cooperation. The formidable Rajan-Thakur combination takes the reader on a tour d’horizon of the erstwhile Shangri-La – a Hindu Kingdom turned into a federal democratic republic by the Maoists employing bullet and ballot.

The book unfolds in three sections. The first is Rajan’s nostalgic recollections of his Nepal sojourn. The second, titled Transition of the Himalayan Kind, tracks every issue under the sun, moving back and forth in time. The third section focuses on Repurposing India-Nepal Relations. These last two sections, jointly authored, blend historical perspectives with contemporary insights.

For India, Nepal is the most important Himalayan neighbour, the erstwhile buffer between China and India with geostrategic avenues leading from the Himalayas into the strategic Indo-Gangetic heartland of India. In a sense, it is the springboard of India’s security concerns. Think of this: India has played a significant role in shaping Nepal’s turning points. This includes restoring the monarchy and sowing the seeds of democracy in 1950, supporting the movement for the restoration of democracy in the 1990s, helping end the civil war in 2005-06, facilitating the first Constituent Assembly elections to mainstream Maoists in 2008 that led to the fruition of Nepal’s new constitution in 2015.

However, the fracas that followed the hurriedly drafted constitution has left a scar on bilateral relations and has not gone away. The book somehow skips mention of the unpleasant incident resulting from Foreign Secretary S Jaishankar’s mission to delay and alter the constitution. It is also one of the clumsy errors made by India.

Rajan mentions that the original anti-India feelings stemmed from the unequal Koshi and Tanakpur barrages, which led to fear and suspicion among Nepalese about hydro-resources cooperation with India. The Tanakpur barrage, built partially on Nepalese soil without authorisation, even cost GP Koirala his premiership. Rajan’s outstanding diplomatic achievement was the agreement in 1996 over the mega-Mahakali Treaty, negotiated with the Communist UML government and signed by the Nepali Congress-led coalition government. This treaty was ratified by an unprecedented two-thirds majority in Parliament, as mandated by the 1990 constitution.

The 1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship, a perennial irritant in bilateral relations, was also raised in 1996 when Foreign Minister Kamal Thapa arrived in New Delhi with a draft of a new treaty. This draft was rejected by the non-reciprocalist Prime Minister, Inder Gujral. Adding to the diplomatic complexities, the first significant Kalapani dispute agitation, orchestrated by UML’s Bamdev Gautam in 1999, coincided with a visit by Indian Foreign Minister Jaswant Singh, who faced uncomfortable questions on the issue. However, Rajan handled all this competently.

Standing out in the book is Rajan’s version of the gory Palace massacre, which he calls the untold story. It is described in great detail and compounded by periodic fears expressed by King Birendra and shared with him. “Excellency,” addressing Rajan, “I have my enemies. I am in the way of what they want to achieve.” The King is referring to Dawood and Co and the ISI of Pakistan, probably in cahoots with Maoist rebels who had always wanted the elimination of the monarchy. At the time, in my copious research about the Royal massacre, I did not hear about the foreign hand as convincingly as it comes out in the book. A lovelorn, drunken Prince Dipendra sprayed bullets, killing the entire royal family except Prince Gyanendra, who was in Pokhara during the weekly Friday dinner for the Royals in the palace. Rajan says Dipendra had roped in D Company and ISI. But then who shot the Prince? That’s the question for Stieg Larsson.

The ISI had built a mini-empire of fraud and intrigue under Maj Assad Bajwa, who later became DG ISI, in Hotel Karnali on Ring Road in Kathmandu. Operation Tufail, designed to subvert Gorkhas in the Indian Army, was planned from there and was busted by Nepali and Indian agencies. A comprehensive account of ISI activities in Nepal during this period, authored by me, can be found in the SUNDAY magazine issue of May 29 to June 4, 1994. So, the ISI was on the go!

There is Rajan’s account of the hijacking of IC 814. During that time, I was trekking in western Nepal when Prime Minister Krishan Bhattarai made a flippant remark about the incident: “aisa to ho jata hai” (these things happen). It was during Rajan’s tenure that the heightened security measure of elevated ladder-point checks for flights to India was implemented in response to the hijacking. This practice persists to this day, serving as a tangible symbol of the lingering trust deficit that permeates India-Nepal relations, a recurring theme in the book.

In 2005, as the civil war neared its end, the various political factions faced critical choices. UML leader Madhav Nepal, representing the Seven-Party Democratic Alliance (SPDA), outlined these options at a conference convened by Rajan in New Delhi. He proposed three possibilities: the SPDA joining forces with King Gyanendra against the Maoists; the King and the Maoists forming an alliance against the SPDA; or, the ultimately chosen path, the SPDA and the Maoists uniting against the King. The irony, as Rajan points out, is that India, having played a role in restoring the monarchy, ultimately contributed to its demise.

In repurposing or reimagining India-Nepal relations, the China factor is a constant. It traces its ominous presence to the warning by the founder of United Nepal, King Prithvi Narayan Shah, in 1746 that Nepal would live dangerously sandwiched between India and China. The book dedicates significant space to China’s growing influence in South Asia, particularly in Nepal. While Nepal once strategically played the “China card,” Beijing now openly interferes in Nepal’s internal affairs, employing its assertive “Wolf Warrior diplomacy.” Nepal is afraid of China but does not consider it a threat. India figures in Nepal’s psyche frequently as a difficult neighbour. The anti-Indianism, the book notes, needs to be addressed. Equally, India must mull over its mistakes, like spearheading the Madhesi movement and then abandoning it; the three economic blockades that hurt the people more than the intended targets; and issues over trade and transit.

The areas of cooperation suggested are hydropower, implementation of power trade and power generation agreements, improved quality and timely delivery of projects, and cultivating our strategic assets like Gorkha ex-servicemen (Agnipath has shut the door to their recruitment). India can also ease issues arising from the open border, revitalise connections with the Nepali security establishment, clear the backlog of irritants like the review of the 1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship, resolve the two per cent of Kalapani border disputes, and review the release of the EPG Report. Although Rajan and Thakur have not made these recommendations directly, they certainly allude to them, as these actions will diminish the trust deficit. They recommend that Nepal be treated as an equal, sovereign, and independent country, which should be respected and treated with dignity. I would say we should pamper Nepal. Maybe coalition politics in Modi 3.0 will make the PMO and Foreign Ministry genuinely focused on ‘Neighbourhood First’.

Kathmandu Chronicle is rich with quotations from numerous literary giants in Nepal. It is fascinating reading, especially the bit about the unsolved puzzle of the slaughter of the Royals and their epitaph scripted by the Maoists.

Ashok K Mehta is a retired Lt General of the Gorkha Regiment, Indian Army & Columnist. He writes and speaks extensively on defence and strategic affairs. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment