views

Note: Always call emergency services (911 in the U.S.) if you or someone else are in serious danger. If a friend or loved one is actively suicidal, call the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988.

- Call emergency services if someone is a danger to themselves or others, or file a petition in your state to get the involuntary commitment process started.

- Individuals can get involuntarily committed if a mental health professional and judge/magistrate feel that it’s best for them.

- The involuntary commitment process involves three key components: an emergency psychiatric evaluation, inpatient treatment, and assisted outpatient treatment.

- Commit yourself to a hospital voluntarily if you need extra care and support to manage your mental illness.

How to Involuntarily Commit Someone

Call emergency services if the situation is dire. Describe the situation calmly and clearly, going into as much detail as you can. Police or emergency responders will pick up the individual and put them in emergency custody where they can be assessed by a mental health professional. Try to be an advocate for the person, if you can. Let the operator know that the individual suffers from mental illness, so the emergency responders can provide appropriate assistance. If you know the person well, you might be able to accompany them to the hospital and provide helpful information to medical professionals while you’re there. Click here for a guide to each state’s emergency hospitalization standards and procedures.

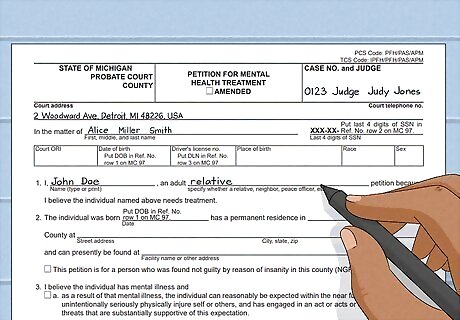

File a petition to get someone committed if it's not an emergency. Visit the courthouse in the district where the person you’re concerned about lives. Once you’re there, ask the clerk for the proper petition forms, and write down all the requested information about the individual you’re worried about.

Talk to a psychiatrist or lawyer to get help with the process. Deciding to get someone committed to a mental hospital is never an easy choice—but it’s not one that you have to make alone. Speak with someone like a psychiatrist, lawyer (preferably one with experience in mental health legislation), or law enforcement officer to get a better idea about what your options are. These experts will know all the ins and outs of your state’s laws and can let you know if involuntary commitment is a good idea for the person you’re concerned about (including minors). Navigate a complex system with compassion. "My sister was in crisis, but the involuntary commitment process felt cold and clinical. This article explained the nuances in a gentle way. Following its advice, I advocated for her humane treatment through a trying time." - Kim I. Make an informed decision for a loved one. "As my husband's health declined, debating commitment was agonizing. This overview of standards, procedures, and laws let me weigh options wisely. I'm grateful for guidance empowering me to handle heartbreaking choices." - Mare B. Gain clarity around an opaque process. "When my roommate's addiction endangered her, I desperately needed direction. Outlining each step to involuntary commitment brought transparency to a confusing situation. Armed with knowledge, I could support her recovery." - Delilah J. Approach treatment through understanding. "As a clinician, I appreciate this article's neutral perspective on commitment. Portraying patients' realities promotes empathy from families and providers alike. We best serve through open hearts and minds." - Matthew I. Did you know that wikiHow has collected over 365,000 reader stories since it started in 2005? We’d love to hear from you! Share your story here.

When to Commit Someone

They’re likely to physically harm themselves or someone else. Has the person in question recently threatened to hurt themselves or someone else? If they’ve displayed a pattern of violent ideologies and behaviors, they might qualify for involuntary commitment in your state. Example 1: A friend is threatening to take their own life and has made attempts in the past. Example 2: A relative has violently threatened their housemate and made them fear for their life.

They’re gravely disabled. Someone is considered “gravely disabled” when their mental illness prevents them from being able to eat properly, clothe themselves, and/or maintain a safe living situation. If a person doesn’t seem capable of caring for their basic needs, involuntary commitment might be necessary. Example 1: A mentally ill relative doesn’t eat consistently and is malnourished as a result. Example 2: A mentally ill neighbor doesn’t remember to wear clothes and walks nude around the neighborhood.

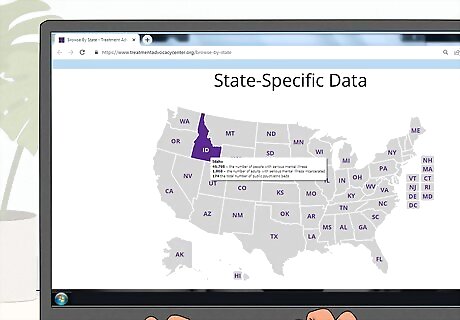

Involuntary Commitment Laws

The process to commit someone to a mental hospital is state-specific. In the United States, the state and local government systems are in charge of handling cases related to mental health (as opposed to the federal government). All 50 states (as well as Washington D.C.) have specific requirements that an individual must meet (related to their mental illness and/or addiction) before the commitment process can begin. Minors can also be involuntarily committed, but the exact procedures are state-specific. Finding your state’s specific requirements can feel like looking for a needle in a haystack—but we’re here to help. You can also click here for specific information and resources about mental health legislation in your state. Individuals suffering from substance abuse can also be involuntarily committed, but it depends on the state. Currently, 38 states and territories (including Washington D.C.) allow this. The only states that don’t allow involuntary commitment for substance abuse cases are New Hampshire, New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Alabama, Illinois, Wyoming, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Idaho, Nevada, and Oregon do not.

There are three different elements of involuntary treatment in the United States. Treatment Advocacy Center provides information about three key aspects of the involuntary treatment process: emergency psychiatric evaluation, inpatient commitment, and Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT). Emergency psychiatric evaluation: A person going through a mental health crisis is taken into emergency custody temporarily. The total detainment time is state-specific, but many states cap emergency custody at 3 days/72 hours. An emergency psychiatric evaluation sometimes segues into inpatient commitment. Inpatient commitment: Depending on specific state laws and procedures, an individual may be held at a mental health facility for up to a set amount of time for treatment. This process may include an official court hearing. AOT: This type of outpatient treatment differs by state. Typically, AOT compels community-based, court-ordered mental health treatment.

Involuntary Commitment Process

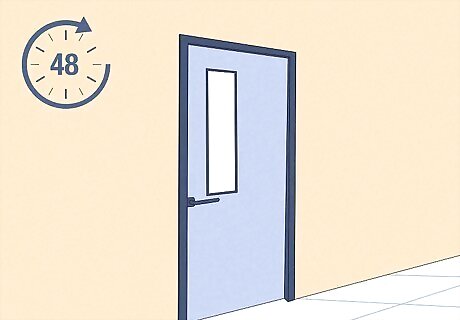

The individual is taken into emergency custody and evaluated. In some states, relatives and spouses can request an emergency hold for an individual; in other places, only psychiatrists, doctors, and law enforcement officers can make the request. Depending on the state, the individual is held temporarily. Many states allow emergency holds to last at least 72 hours, while a small handful of states allow for shorter detainment periods.

A petition is filed for the individual to receive inpatient treatment. Some states allow family members to file this petition, while other places only let mental health professionals get the process started. During this time, a court will decide if the individual meets the state’s criteria for involuntary commitment (like being gravely disabled or a danger to themselves or others). In some cases, the court might recommend supervised outpatient treatment for a person rather than inpatient care. This is known as “step-up AOT.” You might be asked to testify in this court hearing if you’ve personally observed the person’s dangerous behavior.

The individual stays at an inpatient facility. The length of inpatient treatment varies from state to state. Washington and California, for instance, only mandate up to two weeks of inpatient hospitalization, while Massachusetts, Rhode Island, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, Georgia, and Florida all mandate six months of hospitalization. Click here to get a closer look at your state’s procedures. The court typically gets to choose which facility the person goes to.

Hospitalization can be extended if a mental health professional recommends it. Most states require a court order for this process to go forward, while a few states (like Pennsylvania, Maryland, Tennessee, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Wyoming) do not. The length of this extended inpatient treatment also depends on the state—some places, like Delaware and Arizona, cap the extra treatment at 90 days, while other places, like Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, Nebraska, Mississippi, Indiana, Ohio, South Carolina, New Jersey, and Connecticut, don’t have a maximum time limit.

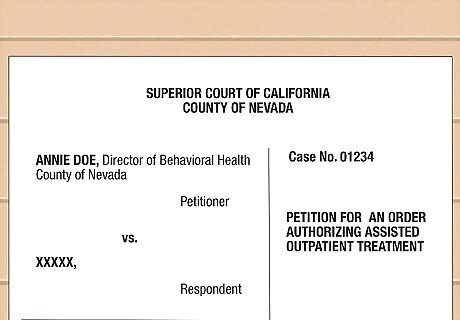

A petition may be filed for the individual to receive AOT. After receiving inpatient treatment, a judge may decide if the individual can transition to court-monitored outpatient treatment—this is also known as “step-down AOT.” When the court allows it, the individual may later switch to a voluntary, community-based treatment plan.

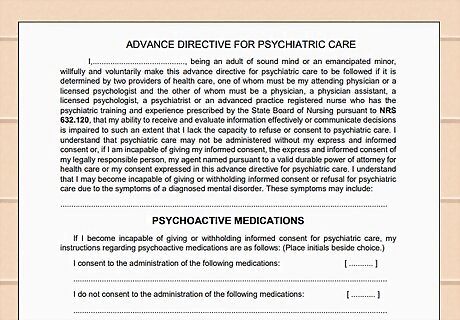

How to Voluntarily Commit Yourself

Fill out a Psychiatric Advance Directive beforehand. List the types of medications you would (and wouldn’t!) like to take during your treatment, if you’d want future visitors, and who you want caring for your home, bills, and other obligations while you’re hospitalized. You can even include the name of someone who can make decisions on your behalf (an “agent”) if you’re ever not in the right frame of mind to make decisions for yourself. Bring this form with you whenever you want to be hospitalized. You don’t have to fill this out, but it can be a big help if you’re considering inpatient mental health treatment in the future. Click here for a master list of PAD forms and PAD FAQs organized by state.

Choose the hospital or treatment facility you’d like to stay at. Do you need round-the-clock, in-depth care for your mental illness, or are you looking for partial care? Search for hospitals and facilities in your area that really cater to your treatment needs. Psychiatric wings in hospitals: 24/7 in-patient care with psychiatrists and therapists Public psychiatric hospital: A separate hospital that offers both short- and long-term care for people with financial difficulties Partial hospitalization: An option that’s less intense than 24/7 treatment programs Residential care: 24/7 care offered in a residential, non-hospital setting Click here to find mental illness treatment centers in your area, and here to find substance abuse treatment centers.

Check in to the facility and get a physical exam. Chat with staff members so you have a good idea of how the treatment center works and what you can expect there. Before you’re onboarded, a doctor will give you a medical check-up so they can take a closer look at your physical health. Before you officially check yourself in, feel free to ask questions like: Who will be treating me at the hospital? How often will I meet with them? Who can visit me when I’m at the hospital, and how long can they visit me for? What is the rooming situation like at your facility? What is a typical daily schedule at your facility?

Check with your facility to see when you can leave. At some hospitals, you can check yourself out whenever you feel comfortable and ready to do so. In some cases, you might need the okay from the hospital—check with the facility and see what their policy is.

Comments

0 comment