views

Starting the Poem

Read examples of children’s poetry. Look for inspiration for your poem by reading the work of others, particularly poetry that has proven to be popular among children. There are several well known poems popular with children, including: “Who Has Seen the Wind?” by Christina Rossetti. “The Dentist and the Crocodile” by Roald Dahl. “Daddy Fell Into the Pond” by Alfred Noyes. “About the Teeth of Sharks” by John Ciardi.

Find inspiration. Children often respond well to humor, especially imagery that conjures up a funny scene or situation. You may be able to generate content for your children’s poem by using an image you find funny or amusing. You could then expand on this image in your poem. For example, maybe you ended up in the path of an angry pigeon on the way to work today. You may then use your amusing encounter with the pigeon as the source of inspiration for your poem. Children may enjoy a humorous retelling of how you managed to escape a persistent pigeon on a busy city street. You can also tap into your own childhood memories and interests as inspiration. Consider what made you laugh when you were young, and what made you curious or intrigued. Doing this can help you get into the mindset of a child and remember what topics made you giggle when you were young. For example, maybe you enjoyed playing with plastic snake toys as a child. You may then remember when your brother tried to stuff a plastic snake up his nose and your attempts to help him remove it. This could then serve as the inspiration for a funny poem about plastic snakes in your nose.

View a situation from the perspective of a child. You can also take inspiration by trying to see a particular situation or scene from the point of view of your audience. Viewing a moment from the perspective of a child can help you to notice details or aspects that may be appealing to them. It can also allow you to describe the scene with creativity and imagination. For example, you may consider how a child might view going to the dentist for the first time. The dentist may appear to a child as a puffy swan in a white coat and the dentist chair might seem like a time machine. You may then be inspired to write a poem about a trip to the dentist that leads to an afternoon of time travel.

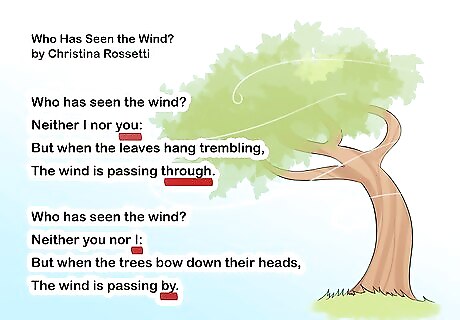

Try the rhyming form. Many children’s poems are written in the rhyming form, where the poem follows a certain rhyming scheme or pattern. Often, you do not need to rhyme every line of the poem, as this can sound contrived, even to children. Instead, you may rhyme only a few lines or words in the poem so there is just enough rhyme for it to sound fun and interesting to your young audience. For example, in Christina Rossetti’s poem “Who Has Seen the Wind?”, Rossetti only rhymes a few words in the poem, with “you” rhyming with “through” and “I” with “by”. This gives the poem just enough rhyme to have a sing song quality, without feeling overdone or too contrived.

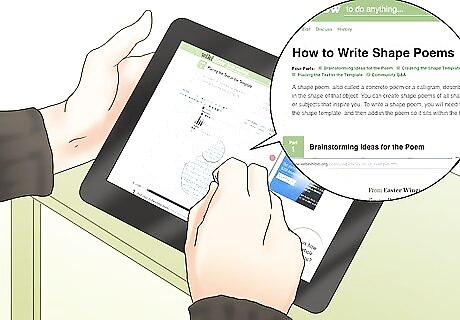

Make a shape poem. Shape poems are great forms for children, as they create an interesting visual for children to look at on the page. Shape poems are often short and concise, as you are limited by the space available within the shape. This makes them good options for poetry written with children in mind. You may decide to do a type of shape poem that has a short number of lines, like a cinquain. This is a five line poem that appears in the shape of a diamond. It is often easy to write and fun to read.

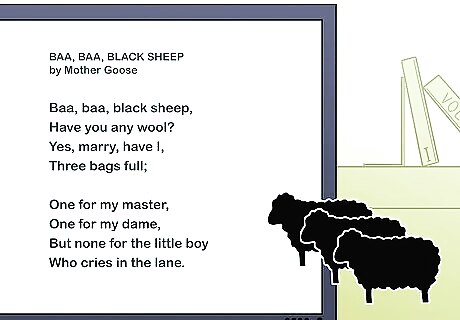

Experiment with different forms. Many children’s poems are written with brevity in mind, as most children have a short attention span and like to be engaged right away. The haiku form, with its short form, is ideal for children’s poetry. Haikus follow a 5-7-5 pattern, with one line that is five syllables long, one line that is seven syllables long, and one line that is five syllables long. You can also try the limerick form The limerick is a type of children’s verse that is known for being funny, ridiculous, and silly. These qualities make it an ideal option for a children’s poem. Limericks are five lines long and have a set rhyme scheme. The first two lines rhyme with each other, the third and fourth lines rhyme with each other and the fifth line repeats the first line or rhymes with the first line. This rhyme scheme gives limericks a bouncy quality when spoken out loud. Some of the more well known limericks are the Mother Goose nursery rhymes. Often, limericks are meant to be silly and nonsensical, making them appealing to children.

Writing the Poem

Include sensory detail. Good children’s poems will engage with all five senses, from smell to sound to taste to touch to sight. Make sure your poem includes details that play with the senses, as children often respond to sensory descriptions. For example, if you were writing a poem about the dentist’s chair as a time traveling machine, you may describe the smells of the dentist’s office and the taste of the plastic dental clamps in your mouth. You may also consider how it feels to sit in the dentist’s chair and the sounds the chair might make as it flies through time.

Use alliteration and repetition. You should also try to include literary devices like alliteration and repetition in your children’s poem. These two literary devices will add playfulness and creativity to your poem, making it more appealing to your young audience. Alliteration occurs when words with the same consonant sound, and often words that begin with the same letter, appear in sequence. For example, in Roald Dahl's’ “The Dentist and the Crocodile”, there is alliteration in the line: “He quivered, quaked, and shook.” Repetition occurs when the same word is repeated in succession or in the same line. For example, in Christina Rossetti’s poem “Who Has Seen the Wind?”, the title phrase “Who has seen the wind?” is repeated twice in each stanza of the poem. The repeated phrase acts as a kind of refrain for the poem, almost like a song.

Add a twist or surprise at the end of the poem. Humor combined with a twist or a surprise can be a great way to engage children and make them laugh. A twist or a surprise adds a layer of silliness to the poem, a quality most children will appreciate. You may include a twist ending or a surprise moment at the end of the poem. For example, in Roald Dahl’s “The Dentist and the Crocodile”, the twist ending occurs when the owner of the crocodile appears at the dentist. She reassures the dentist, who is by now frightened of the crocodile, “'Don't be a twit,' the lady said, and flashed a gorgeous smile./'He's harmless. He's my little pet, my lovely crocodile.'" This twist ending is sure to make children laugh with the silliness of having a pet crocodile, at the dentist no less.

Polishing the Poem

Ask children for feedback on the poem. Once you have completed your children’s poem, you should go straight to your target audience for feedback. Read the poem out loud to your own children or to your classroom of children. Listen to their reactions, noting when they laugh or giggle. Pay attention to how they react to the form of the poem and your word choice. If the poem falls a little flat, you may need to revise it so it is more appealing to children. This may mean including more sensory detail or shortening the poem so it is quick, fast, and funny. You may also consider adding in a twist ending to surprise your young audience and make them giggle.

Revise the poem for clarity and brevity. You should revise the children’s poem so the language is simple and clear. You should also make sure the poem is short and to the point, as children have a limited attention span and like to be engaged right away. You may also use the feedback from your child audience to revise the poem. Take their constructive criticism seriously, as you want to make sure the poem is appealing to your target audience.

Consider distributing or publishing the poem. If you think your poem is strong, you may decide to distribute the poem to your children or to young students in your classroom. You may also decide to send out the poem for publication to magazines and journals that publish poems for children. If you do decide to send the poem out for publication, make sure you read a few sample poems in the magazine or journal to get a sense of what they are looking for. Publications are more likely to accept your work if it fits with the style and tone of other poems they have published.

Comments

0 comment