views

Explaining How a Text Works

Define the components of a story so students can identify them. Depending on how old your students are, you could create a large poster that hangs in the front of the room for everyone to see, or you could hand out individual worksheets with a breakdown of important terms and definitions. When your students read, ask them to identify as many different parts of the story as they can. Here are some terms to include: Characters—who are the people in the story? Setting—where does the story take place? Plot—what is happening in the story? Conflict—what are the characters trying to do or overcome? Resolution—how does the conflict get resolved? Your approach to teaching these components will differ depending on the age of your students. For younger students who are still in grade school or middle school, have them write down what or who they identify as being the main characters, where the story takes place, what happens in the story, and how conflict is resolved. For older students who are in high school or college, ask them to write a 500-word summary of the main points of the text.

Tell the students what their goals are for reading a certain text. Whether it’s simply to be able to summarize the text or if they should be learning something new, let them know what they should be paying attention to as they read. Verbalize this goal and also write it down at the front of the classroom so that students can refer to it when they need to. For example, you could say, “While you’re reading, try to figure out how our main character decides to resolve this situation. Would you have done anything differently?” Verbalizing to students what their goal is will help them approach new texts with a similar mindset. It’ll become a habit that prepares them to receive new information. This may not be as much of a concern for older students who are in high school or college, but for younger students it can be very helpful for them to know what to pay attention to as they begin to read.

Ask the students to pay attention to pictures and titles. Before you start reading something new, whether you are doing it with your students or if they’re reading independently, always start by noting the title of the text and any accompanying graphics on the cover or pages. Similarly, if there are multiple chapters, pause at the beginning of each one to read the title. Titles and pictures can often give us clues about what the text is going to tell us. They can help students focus their attention. Ask your students how they would change the titles or illustrations if they were the author. This helps them think about what those aspects of a text actually communicate.

Help students identify sections of text that they don’t understand. Whether it’s vocabulary, a plot point, or a character question, being able to say what they don’t understand is a huge part of helping your students overcome comprehension issues. Encourage your students to either ask you questions directly or write down questions they have about the text. Maybe they don’t know why a particular character is behaving a certain way, or maybe they don’t know what a certain word means. By pinpointing the problem, you can show them how to find the answers. Helpful questions for your students to ask are: (1) Why did the author include this section? (2) Why did this character do this particular action? (3) I wonder why … If you are working with grade school or middle school students, ask them to show you where they are having trouble with comprehension and then help them learn how to articulate that problem, as they may not have the vocabulary for it yet. If you’re working with older students who are in high school or college, encourage them to see you after class or during your office hours to discuss any issues they are having with reading comprehension.

Teach your students how to use context clues to answer questions. If your students have trouble with vocabulary, teach them to use the surrounding sentences to figure out what the likely meaning of the word is. Similarly, if they’re misunderstanding the plot of the text, have them revisit the title and first several lines of text to pay attention to the setting of the story. For example, let’s say your student doesn’t understand the word “vexed,” but they know that in the same sentence the author writes that there is shouting and arguing—from that information, they can deduct that “vexed” most likely means angry or annoyed. For younger students, use a specific text designed to highlight context clues as an example of how your students can do the same with other things they read. Spend an entire class period working through this example and asking your students to identify things like the tone of a text, the setting, the plot, and other vocabulary words that might help them interpret the text better. If you’re working with high school students, you could also teach them about using other resources to help them make connections, like pausing while they read to look something up on the computer or on their phones, if they’re allowed to use them in class.

Help your students connect the readings with their lives. Ask your students how the story made them feel, or how they would feel if they were one of the characters in the story. Ask them if it reminds them of a situation in their own life or in another story they’ve read. Have them share what that situation was and how they see it as being connected to the text. Also, asking your students to think about their opinions about the story is important in helping them develop critical thinking skills. If you are working with grade school students, focus more on the feelings aspect of a situation, whereas with middle and high school students, you could start talking about the ethical implications of a text for a more in-depth conversation. Ask your older students to write responses to the text explaining how they felt and how they think the author accomplished making them feel that way.

Practicing Active Reading

Share “think alouds” during reading times with younger students. If you are reading to your students or if you’re all taking turns reading out from a shared text, encourage questions and “wonderings” along the way. For example, after reading a sentence about an action a character took, you could pause and say, “I wonder why our main character decided to do this rather than something else.” “Think aloud” show students how to pause and question as they read, rather than simply focusing on finishing the text as quickly as possible. One great way to encourage “think alouds” is to hold a Socratic Seminar. This is a student-led discussion, in which the students share and build off of one another’s ideas and questions.

Teach students how to take notes and remember important details. If your students are allowed to make marks in their books, teach them to circle the names of important characters, put checkmarks beside important plot points, or even highlight or underline areas they think are important. Or, you could also encourage your students to take notes on a piece of paper. Especially if students have trouble remembering details, marking them in the text or writing them down can help imprint that information in their minds. If you’re working with grade school students, you may want to focus on teaching them how to take simple notes, like naming main characters or how to organize information by chapter. For older students, you can get more in-depth with note taking by helping them create study guides and even having them journal about their reactions to a text in addition to general note taking. If any of your students are visual thinkers, encourage them to create concept maps to visually organize different elements of the material. For example, they might make a concept map showing relationships between different characters or plot points.

Ask your students to verbally summarize what they read. Have them focus on identifying the main characters, the conflict, and the resolution of the story. Knowing that they’ll be speaking about the story afterwards encourages students to pay attention to the plot points as they read. And being able to synthesize information and repeat it back shows that the reader comprehends the text. You could also have students work in groups after reading a text. Have them talk about what they thought the main point of the story was, how they felt about the characters, and what questions they had as they read. For younger students in grade school and middle school, ask them to come up with a 5-6 sentence summary for a text. For older students, consider asking them to prepare a 5-minutes verbal summary that they will present in front of class or in a small group.

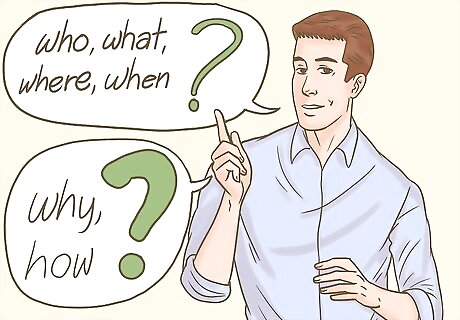

Utilize “thin” and “thick” questions to improve reading comprehension. The “thin” questions reflect the main components of a story: who, what, where, and when. “Thick” questions help your students dig deeper—try asking some of these “thick” questions: What if? Why did ____ happen? What do you think about this? What might happen in the future? How do you feel?

Create graphic organizers to help older students organize information. Graphic organizers are things your students can create as they read a text to help themselves organize information as they read. They can use them to plot out the timeline of a story, or to understand characters’ emotions or decision-making processes. Search online for different formats and have a class session where you teach your students how to use graphic organizers. Venn diagrams, flow charts, summary charts, and cycle organizers are all popular graphic organizers. Graphic organizers are great because each student might have a different way of needing to write things out. If you can, help your students figure out what style will work best for them.

Hang up visual anchor charts in your classroom. Anchor charts are posters that emphasize different aspects of reading. They’re great to have hanging up around the room so that your students can reference them while they’re reading independently. For example, you could create an anchor chart about context clues, sounding out words, visualizing texts, and summarizing information. Check out Pinterest or websites devoted to teacher resources to get ideas for your own anchor charts! There are tons out there to choose from. You could also emphasize a different anchor chart every week to help your students focus on different aspects of reading comprehension. Visual charts can be helpful for all students, no matter their age.

Ask your students to create a “mental movie” of the text. Have the students visualize the action (or whatever is being described in the text) as they read. Then, ask them to replay the movie in their mind when they are done. This can help them solidify their understanding of the material. You can also help them reinforce their visualization by having them draw a simple storyboard or act out a little bit of the “movie.”

Assigning Homework and Evaluating Progress

Give your students small reading assignments and questions to answer. Depending on what you’re working on in class, give your students homework that echoes the lessons you’re learning in the classroom. For example, if you are learning about context clues, give your students a small reading assignment and a worksheet with questions regarding the context clues that are present in the text. When the homework is due, have your students work in small groups to talk about the clues they found. For older students, you could ask them to read several books over the course of a semester and write 500-word responses to each one detailing how they thought the text was crafted and what it made them think in response.

Have your students keep a journal where they write responses to texts. This is something students of all ages can work on. It can be a physical journal or an electronic one, depending on your preference. Ask them to write a response to the texts you assign, detailing why they think the characters made the choices they did, what they located as major plot points, and how they think the story could have gone differently if people made different decisions. Have your students turn in their journals 3-4 times throughout your semester or year together. This provides some accountability but also allows them to develop their own work habits.

Research assessment tools for students of different ages. There are some state-mandated tests that may give you some good information about the skill-level of your students, but there are also some great online resources you can use throughout your curriculum to check in and see how your students are progressing. From phonemic awareness to understanding how a text is structured, make sure to test your students on subjects that you’ve already covered in class. If you find that a student isn’t doing well on assessment tests or class assignments, they may need a little extra help. You could offer extra credit or opportunities for one-on-one tutoring time to focus in on areas that could be improved.

Comments

0 comment