views

X

Research source

Putting your dog in the hospital is really the best option. Your vet knows how to treat a dog with parvo and will be able to administer the medications and liquids he needs. However, if you can't afford to put your dog in the hospital, you can try to treat your dog's intestinal parvo at home by providing fluids both under the skin and orally, giving medications, and following certain protocols.

Subcutaneous Fluids

See your vet right away if your dog has parvo. In the majority of cases, parvovirus is fatal without effective treatment. If you can, it's usually best to let your dog stay at a veterinary hospital if they're infected with parvo. Your dog might need IV fluids, medications to stop their nausea and vomiting, and sometimes a feeding tube or even blood transfusions. However, if your dog is only mildly to moderately sick, you may be able to treat them at home under your vet's supervision. Keep in mind that parvo is also extremely contagious, and your vet will be able to isolate your dog more effectively than you can do at home. Ask your vet what symptoms would indicate that you need to bring in your vet for treatment.

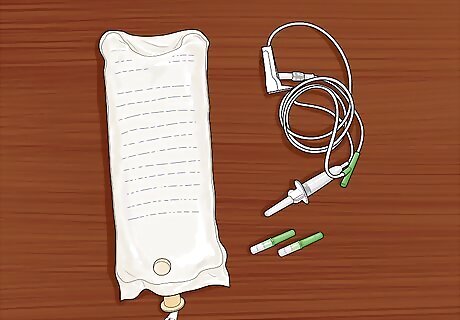

Use subcutaneous fluids to rehydrate your dog while they're vomiting. Since your dog won't be able to hold down fluids while they're vomiting profusely, they can quickly become dehydrated. You can help by giving them subcutaneous fluids, which are delivered under the skin. Ask your vet exactly which fluids to use—veterinarians typically recommend a saline (isotonic sodium chloride) or lactated Ringer (LR) solution. They can also advise you on what dose to use and how often to give the fluids. IV fluids are more effective for hydrating your dog, but these need to be administered by a vet. In seriously ill animals, their circulation is often so poor that the fluids are poorly absorbed from beneath the skin—you'll need to take the dog in for IV fluids for them to have the best chance of recovery. Your vet will typically provide you with a kit that contains a fluid bag, a tube and spike, and a subcutaneous needle. If you can't get to your vet, ask the vet clinic to recommend a veterinary supply store near you where you can purchase these items.

Attach the tube to the fluid bag. The subcutaneous fluids should be contained in a large bag, similar to an IV bag. Lay the bag on a flat surface and remove the plug from the end of the bag. Then, open the bag that holds the tube. One end will have a spike that you can insert into the fluid bag. Pull the cap off the spike, then push the spike into the nozzle on the end of the fluid bag. However, avoid touching the area where you're going to insert the spike—this is sterile, so you don't want to contaminate it. Before you connect the tube, make sure the clamps on the tube are closed so the fluids won't flow out when you insert the spike. Properly dispose of the needle you're using away when you're done. Don't reuse a needle, as it can contaminate the fluids Talk to your vet about whether or not it's appropriate to keep fluids for more than one use.

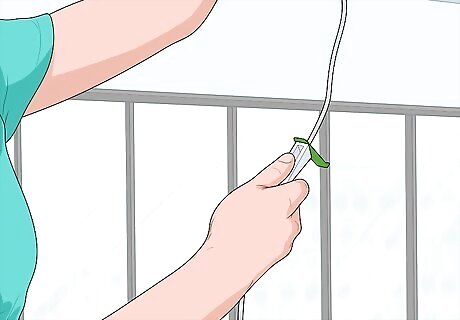

Hang the bag or hold it up. Once the tube is connected to the fluid bag, hang the bag from something like your shower rod or a doorknob. If you don't have anything to hang it from, ask someone to hold it for you—it just needs to be placed somewhere higher than the dog, because gravity will help the fluids flow more easily.

Bleed any air out of the tube. Undo any clamps that are on the tube. You'll see fluid start to collect in the small chamber under the bag. Then, it will start to flow into the tube. Let the whole tube fill up with water to make sure there isn't any air in the line. Then, reclamp the line. If there's any air in the line, it will go under your dog's skin, which could be painful.

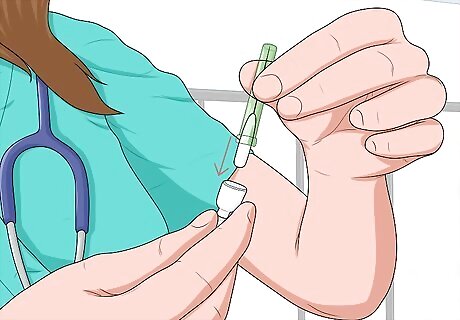

Attach the needle to the tube. Take the cap off the end of the tube, then remove the cap from the bottom of the needle. The two ends you just uncapped will fit together—give them a twist to attach them securely. Don't touch the end of the tube before you attach the needle—this should also remain sterile.

Make sure your dog is settled. It's a good idea to calm your dog before you do the actual injection. Have them lay down, and if possible, have someone else hold on to them while you're working so the dog doesn't try to run away. If your dog is really anxious, it can help to wrap your dog in a towel to calm them. EXPERT TIP Colleen Demling-Riley, CPDT-KA, CBCC-KA, CDBC Colleen Demling-Riley, CPDT-KA, CBCC-KA, CDBC Canine Behavior Consultant Colleen Demling-Riley (CPDT-KA, CBCC-KA, CDBC) is a Canine Behavior Consultant and the Founder of Pawtopia Dog Training. With more than 20 years of experience, she specializes in creating and customizing dog management programs for dog owners. She is a Certified Pet Dog Trainer-Knowledge Assessed, Certified Behavior Consultant Canine-Knowledge Assessed, Certified Dog Behavior Consultant, and American Kennel Club Canine Good Citizen Evaluator. Colleen is a member of the International Association of Canine Professionals and has been a featured expert in national media including the New York Times, Woman’s Day, Readers Digest, Cosmopolitan, and Yahoo.com. Colleen Demling-Riley, CPDT-KA, CBCC-KA, CDBC Colleen Demling-Riley, CPDT-KA, CBCC-KA, CDBC Canine Behavior Consultant If your dog is in pain, stay calm. Dogs are sensitive to their owner's emotions. If your dog is in pain and you start getting nervous or panicky, your dog will sense your distress and feel more pain and stress. Whatever the situation, approach it calmly to help your dog feel reassured.

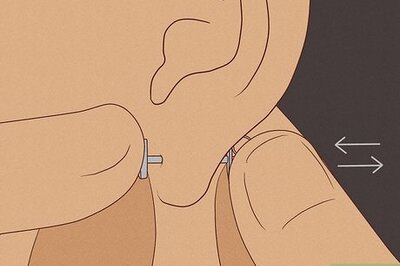

Give the injection between your dog's shoulder blades. Pinch the loose skin on your dog's back to create a tent shape. Hold the needle so the bevel—or angled end—is pointed up toward the ceiling, then insert it straight into the loose skin in one quick motion. Hold it in place securely, then open the clamp so the fluids can flow under the dog's skin. You'll see the fluids dripping into the chamber and running through the tube. You can gently squeeze the bag to help the fluids move faster, but keep in mind that this may make some dogs feel anxious. The fluids will make a bump under the skin, but they will be taken into the bloodstream soon as long as the dog is not in shock and has a good circulatory system.

Remove the needle when the fluids are injected. Place a piece of gauze over the needle, then slide the needle out from the skin. Hold the gauze in place for a few moments to keep the fluids from leaking out. If any fluid does leak out, it may have a little blood in it—that's normal. Over time, the bump where you administered the fluids should disappear as the fluids are absorbed. If it doesn't, contact your vet. Talk to your vet about exactly how much fluid to use and how often to repeat it. However, a good rule of thumb is to give them 40ml of fluid for every 1 kg (2.2 lb) that your animal weighs. Do that every 8 hours.

Oral Fluids

Provide oral fluids once your dog stops vomiting. You only give subcutaneous fluids while you are trying to slow down your dog's vomiting. Once your dog is able to keep fluids down, you can use an electrolyte infusion meant for dogs to help them get hydrated. Wait until your dog has stopped vomiting for 6-12 hours before you give them anything to drink. Your dog might prefer one of these rehydration drinks to plain water, so they may be more likely to accept it.

Use a catheter syringe to control how much fluid your dog gets. Even after your dog starts to recover, they might get sick again if they drink too much, too fast. To avoid that, use a catheter syringe to administer the rehydration fluid. These syringes have a strong, wide tip, and you don't have to put a needle on the end to provide oral fluids.

Fill the syringe with fluids. Use the syringe to draw up fluids. Stick the syringe in the bottle, and pull back the plunger to the appropriate line. Give 2 to 4 cc (cubic centimeters) for each pound your dog weighs per hour.

Keep your dog secure while you administer the fluids. Your dog will likely be weak from parvo, anyway. However, if your dog resists, ask someone to help you hold them while you administer the oral fluids. Try bracing the dog against your body so that he can't move around as much. Hold him with one arm while you give him the liquid with the other.

Put the syringe in the dog's mouth. Start by inserting a finger into the mouth between the cheek and the teeth. Push the syringe gently in. The jaw does not have to be open. Push the plunger down, releasing the liquid into the mouth. The liquid should drain through the teeth. Squirt in a small amount of the liquid at a time, pausing to let your dog swallow each time.

Don't tilt the dog's head back. It may be tempting to lift your dog's chin to help the liquid drain to the back of the throat. However, doing so can make your dog breathe in the liquid, causing aspiration.

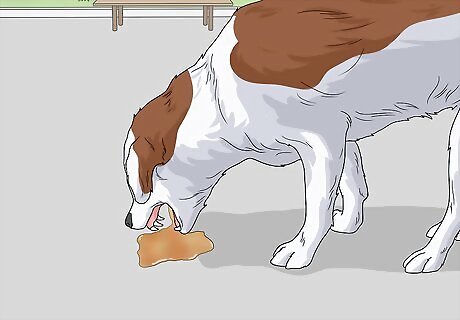

Watch for vomiting. Keep an eye on your dog after giving them liquids. If your dog throws it up, wait until later to try giving oral fluids again.

Medications

Slow down the vomiting with anti-emetics. Your veterinarian can provide you with drugs to ease the vomiting. Since you can only treat the symptoms of parvo, not the actual disease, this step is one of the most important to provide comfort for your dog. Your dog may also need a medication to control diarrhea. Talk to your vet about the way to administer these medications, as well as the size of the dose and how often to give it.

Give antibiotics if your dog has another infection. Though antibiotics will not do anything for the parvo, they will stop another infection from taking over. If the vet suspects your dog has a secondary infection, they'll provide you with antibiotics. Follow the administration and dosage directions on the bottle.

Try pain medications to ease your dog's discomfort. Your vet may recommend that you give your dog pain medication to help them with abdominal pain due to parvo. This might make your dog feel comfortable enough to start eating again—which could help them start on the path to healing. Don't give your dog pain medications for humans—these can be toxic.

Try the new parvo protocol recommended by Colorado State. One study found that using a certain medication regimen at home greatly increased a dog's chances of surviving. The first part of the regimen is giving a strong anti-nausea drug, Maropitant, once a day. The other part of the regimen is having the vet give one dose of long-lasting antibiotic under the skin when the dog is diagnosed (Convenia), and then having the pet parent give subcutaneous fluids 3 times every day. Ask your vet if these drugs are right for your dog.

Prevention and Aftercare

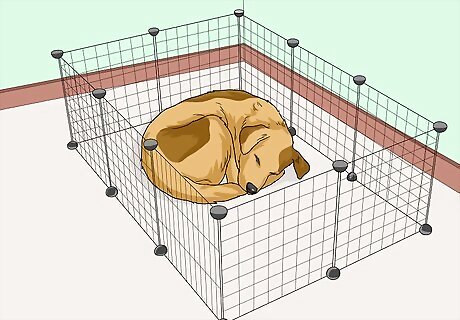

Isolate your dog. Parvo is extremely contagious, which is one reason it is such a difficult disease. Your dog can remain contagious for as long as 2 months. Make sure to isolate your infected dog from other dogs in the family if possible, and keep them away from public spaces while they are still contagious. Parvo is mainly passed through feces and fluids passing from one dog to another. It can even be passed by your dog sniffing another dog. If you have other dogs in the house, make sure that your sick dog is using the bathroom in a different area from your other dogs, as your dogs can catch it from the sick dog's feces as long as 2 months after the symptoms have passed.

Feed your dog bland food. Once your dog has stopped vomiting and shows an interest in food, start with bland food, like boiled chicken, white rice, or pasta. Ask your vet for other options. Don't let your dog eat a lot at one time, even if they seem hungry—this can cause vomiting and diarrhea to return. Instead, give them smaller meals while they recover.

Disinfect your home after a parvo outbreak. Mix 1 part water with 30 parts bleach. Use that mixture to sanitize hard surfaces in your home, especially ones where your dog has been. That will kill the virus—but it only works on hard surfaces. For other areas, such as carpet and couches, wipe as clean as possible, and then get them steam cleaned. You might also consider quaternary ammonia for cleaning soft surfaces. For outdoor areas, the best you can do is pick up any of your dog's feces and water the yard a bit more often. The dilution can help lower the amount of virus in your yard over time, and the sun will also kill some of it. Try to keep other dogs out of the area for at least a few weeks.

Bathe your dog. Once your dog has stopped showing symptoms, give them a bath to help get rid of any virus that might remain on their fur. Just be sure to use warm water and dry them off thoroughly afterward so they don't get chilled.

Comments

0 comment