views

“Miyaan, kaptaan banoge?”

One of Indian cricket’s most iconic sentences, Raj Singh Dungarpur’s left-field question threw Mohammad Azharuddin completely off guard. It was early 1990, the Indian team was to embark on a tour of New Zealand. Krishnamachari Srikkanth had led the side to a merited 0-0 stalemate in Pakistan a few weeks previously, but his form had been ordinary and the chairman of selectors felt the team needed a dynamic new leader. Thus was born the legend of Azhar the Indian captain, a position he held over two stints until the 1999 World Cup.

“Ek aur karega?”

It doesn’t quite have the same touch of the dramatic as Dungarpur’s query, but these three words were impact Indian cricket equally significantly. On a sweltering January Saturday at the WACA ground in Perth in 2008, a wiry 19-year-old had sent down seven excellent overs without any reward, repeatedly beating Ricky Ponting’s outside edge without gaining the approval of the cricketing Gods. Anil Kumble was on the verge of taking off the somewhat crestfallen teenager when, like in the movies, Virender Sehwag sprinted to his skipper and urged him to give his Delhi mate another over.

Ishant Sharma: From First Fifer Against Pakistan To Great Performance at Lords – 10 Moments of Glorious Test Career

Concerned because of the length of the spell in searing heat, the captain directed these three words at his young charge.

“Haan, karunga,” Ishant Sharma replied, high-pitched, itching to have another go at the Australian captain.

As we moved to the edge of our seats at the WACA in anticipation, Ishant ran in like the wind. The first ball of an eighth consecutive over exited his right hand beautifully, the seam tilted towards the slips as it cut a lovely arc through the air. Ponting, mentally drained and physically battered, seemed hypnotised. As a moth to flame, his bat was fatally attracted to the little red sphere, which caught the outside edge and lobbed to first slip, to be lovingly embraced by Rahul Dravid’s grateful hands. The tyro had delivered, ‘ek aur’ had worked.

It was that spell, that wicket, which remained Ishant’s identity for long. Perhaps sub-consciously, that spell also solidified the belief that here was a workhorse who could tirelessly send down over after over in extenuating circumstances without sacrificing pace or control. Subsequent captains used him as a stock rather than a strike bowler until the real Ishant stood up, nearly a decade after his Test debut in 2007 against Bangladesh.

Kohli On Verge of Surpassing Dhoni To Become Most Successful Test Captain At Home

For the first half-dozen years of his Test career, Ishant played second fiddle to the peerless Zaheer Khan, rejuvenated after a county stint with Worcestershire in 2006. Zaheer’s retirement in early 2014 had just been preceded by the arrival with a bang of Mohammed Shami, which meant despite his status as the senior quick, Ishant ceded strike-bowling status to the younger man too. Occasionally, he produced bursts of brilliance, like when he bounced England out at Lord’s in 2014 on his way to a seven-wicket haul, but for the most part, he was the ‘holding’ man with specific instructions, it appeared, to keep one end tight. A wicket was looked at as a bonus. Ishant must have hurt, but he didn’t complain.

After all, he hadn’t complained when the pundits moaned his shortness in length which precluded outside edges on the numerous occasions he beat the bat. He hadn’t moaned when experts urged him to pitch the ball further up but had no suggestions to offer on how to do so without sacrificing pace. He hadn’t whined when his resources weren’t used to the hilt, when he wasn’t given the freedom to do what he did best, shackled as he was by the diktats of the situation, of the team management. He hadn’t lashed out when he was repeatedly criticised for an unremarkable strike-rate and an unflattering average despite the mounting number of Test appearances. That wasn’t Ishant.

Then, like his mentor, Ishant too went away to the county circuit for two months in the summer of 2018, and returned a more confident, less silent version. His bowling had already shown signs of transformation towards the end of 2017; from the middle of the next year, Ishant has been an epitome of penetrativeness, his numerous dalliances with injuries doing little to wean away his enthusiasm or his effectiveness.

WTC is Like World Cup for me, Want to Help Team Qualify for Final – Ishant Sharma

Ishant didn’t set the county season alight. He bowled a little under 150 overs for Sussex, picked up 15 wickets with a best of four for 52 and boasted an impressive average of 23.06, but like with Zaheer, the responsibility of being the overseas pro on the park and of managing his life on his own off it reinvigorated him. Crucially, in coach Jason Gillespie, the former Australian fast bowler, he finally found a voice of reason, a voice that not only identified a problem but offered a solution, too.

“A lot of people would tell me that I need to increase the pace of my fuller deliveries. No one told me how to do that. It was Jason Gillespie who gave me the solution,” Ishant has admitted publicly. “He told me that in order to increase pace for fuller deliveries, you don’t just release it, but hit the deck so that it should target the knee roll.”

His journey of self-realisation had been given further shape by Gillespie’s wisdom. The emergence of Jasprit Bumrah meant India now had a pace attack for the ages – the unique Bumrah, the skiddy Shami, the seasoned Ishant, with several excellent quicks waiting in the wings. It’s hardly a coincidence that India have travelled better in the last three years than ever before.

Bumrah has been quite the cynosure since his Test debut in January 2018. In 18 appearances, the exceptional exponent of swing, the yorker and wicked slower balls has snaffled 83 wickets – average 21.87, strike-rate 48.6, five five-wicket hauls. Wonderful numbers, even if only one of those matches has come on Indian soil.

But what of Ishant in the same period? 20 Tests, 76 wickets, average 19.34, strike-rate 42.5, four five-fors. When you throw in the fact that he has played nearly a third of those games at home (seven Tests), it makes for even more stunning reading. Bumrah has got most of the accolades, but Ishant has actually outperformed the younger man. Silently, without fuss or fanfare, but with the respect and admiration of the men who matter – those with whom he shares a dressing-room.

Earlier this month, he became just the third Indian quick to reach 300 Test wickets. In the pink-ball Test at the grand new Sardar Patel Stadium in Motera, Ahmedabad, Ishant will join the legendary Kapil Dev as the only pacer from his country to feature in 100 Test matches. That’s a fantastic accomplishment for someone still only 32.

Ishant dislikes the moniker that’s been associated with him for the last few years. “People keep saying Ishant 2.0, which make it sound like I am a robot!” He sure is not, but how can you not call him Ishant 2.0 when you sample his returns till end of 2016, and those subsequently?

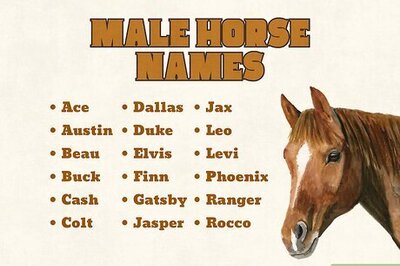

ISHANT IN NUMBERS (matches, wickets, average, strike-rate, five-wicket innings hauls)

May 2007 to Dec 31, 2016 – 73; 212; 36.47; 66.5; 7

Jan 1, 2017 to date – 26; 90; 22.20; 47.9; 4

Overall – 99; 302; 32.22; 60.9; 11

Ishant’s unusual journey from unflagging workhorse to unquestioned leader of a fiery pace pack has few parallels. It’s a journey of hope and heartbreak, of immense potential largely unfulfilled, but he has now got off roller-coaster and is showcasing what might have been. Ishant has 18,420 deliveries behind him in Test cricket alone, but is as driven as he was when he debuted at 18. Really, they don’t make ‘em like him anymore.

Get all the IPL news and Cricket Score here

Comments

0 comment