views

Kolkata: “With me, you will have exposure problems,” a smiling Nirupam Sen said, even as my cameraman struggled to get that perfect frame before the start of an exclusive television interview, which the Bengal industries minister was supposed to give at his chamber in the state Assembly House.

It was the summer of 2007, a landmark year for Bengal’s political history as many would later look back and say, and the Marxist government of the day had well and truly started implementing its industrial reforms policy by inviting the Tatas to set up their small car factory in Singur.

Sen was perceived to have masterminded that reforms drive as the number two man in Buddhadeb Bhattacherjee cabinet and as the chief minister’s most trusted lieutenant in the CPI(M)-led Left Front government. For a party that had industry way down in its priority list when it assumed power in the state back in 1977, so much so that the department was only earmarked for Front ally Forward Bloc with Kanailal Bhattacharya as minister, these were exciting times for the CPI(M).

For the first time in almost three decades, Sen, a CPI(M) heavyweight from Burdwan district, had taken up the mantle for industry and industrial reconstruction in 2001 and was on the verge of taking the next big leap of faith in lines with Jyoti Basu’s new industrial policy of the mid-90s: government acquisition of farmland for private sector industry. It was, doubtless, a bold move for a government which was voted back to power with an overwhelming majority in 2006 for its record seventh consecutive term.

The fact that move later turned out to be the nemesis for the longest-standing government of Independent India and catapulted Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress to power is, needless to say, history.

It was in this context that Sen had agreed to sit for a crucial interview. A dark-complexioned Sen was seated opposite me in his quintessential milky white, half-sleeve shirt when my cameraman was trying to get the lights right. Acknowledging the difficulty of getting the proper exposure of the two contrasting shades, Sen then went on to divulge his interest in photography, albeit in his typical low-key demeanour. It surely was an interesting note to start an interview where focus would lay on politics, policies and number crunching.

Sen’s mild-mannered yet firm attitude at work is recalled by his comrades and political opponents alike. Son of a school teacher, he started off following his father’s footsteps before becoming a party whole-timer in 1968. Twenty-one years later, in 1989, Sen became the CPI(M)’s district president of Burdwan in central Bengal, a region where the Congress continued to wield considerable influence. And by the time he was offered the charge of Bengal’s Industry, Public Undertakings and Industrial Reconstruction, Planning and Development departments in 2001, Sen was already a member of his party’s highest decision-making body — the Central Committee.

At that time, many believed that the Bhattacharjee-Sen duo, who reflected the majority opinion of the CPI(M)’s so-called Bengal Brigade on how to tackle the crisis generated on account of the state’s stunted growth figures and unemployment-related angst, exercised their growing influence within the party to fast track industrialisation in the state. Arguably the most successful economic reform in Bengal achieved by the Left, the Land Reforms programme, was already showing signs of backfire because fragmented landholding was failing to provide for the enhanced aspirations of the peasantry.

Sen’s initial efforts gave dividends. The IT sector received boost. Investments started trickling in the manufacturing sector. The small and medium industries started looking up. Restructuring the state’s power sector was successfully concluded. And divestment of loss-making public sector units, including the iconic Great Eastern Hotel in Kolkata, could be carried out without major hurdles from trade unions. But then, Singur and Nandigram happened.

Much to the chagrin of some senior comrades in the CPI(M), the perception was that the Bhattacharjee-Sen duo steamrolled the industrial reforms process without considering the pulse of the grassroots. Some, during later introspection, even called it “arrogance” of power. But Sen was always sure about what he was doing. He never regretted a single move he made, some of which had allegedly changed the political fortunes of his party.

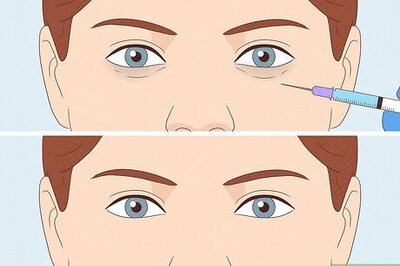

Singur and Nandigram weren’t the only places which singed Sen’s political career. He was forever blamed by his political opponents for having led the massacre on the Sain family residence in Burdwan in March 1970 where two brothers of the family and an unrelated person were brutally murdered and the eyes of a third brother gouged out allegedly by CPI(M) workers for supporting the Congress. Sen was never found guilty by court and his party cried hoarse at “Congress conspiracy” for involving him in the case to exact political vendetta.

But these controversies notwithstanding, Sen would be remembered for his grit to try and exorcise the political past of Bengal, which rendered it from being the most industrially advanced state of the country at the time of Independence to one which began witnessing record brain drain a few decades later. He struggled to achieve that goal as much within his party as outside of it. Whether his “right ideas” could have been implemented better is another debate. But few question his vision of Bengal where fulfilment of youth aspiration acquired centre stage.

Sen used his oratory skills to keep voicing his views within and outside his party, even after he was voted out of power in 2011, lock stock and barrel until a cerebral stroke in 2013 left him partially paralysed and confined him to a wheelchair. His quiet exit from the party Politburo two years later signified he had given up.

But not before he gave it his best shot… in his firm, yet mild-mannered demeanour.

Comments

0 comment