views

Nothing works like clarity in getting things done. And the world needs to get down its carbon emissions to keep it habitable for most of us in the not-too-distant future. Naturally, then, most climate conversations revolve around carbon, with political and business leaders jumping onto the Net Zero bandwagon. So why muddy the waters, by talking about, um, water?

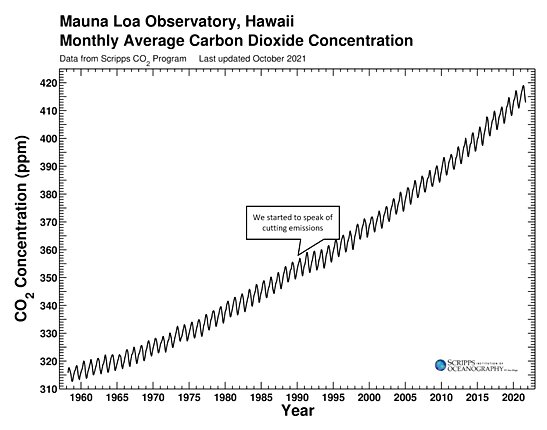

Because while the world has been talking about reducing carbon emissions, those emissions themselves have been rising.

Figure 1: Rising Carbon Levels, Scripps CO2 programme

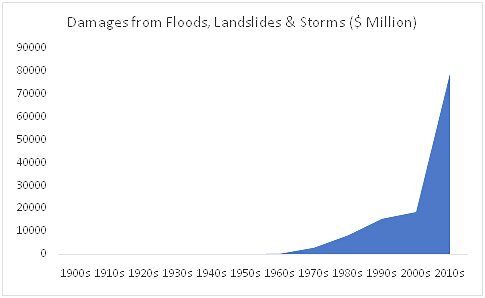

And now, carbon concentrations are so high that the world has warmed quite a bit. And the warmer climate is making itself felt through water. The climate speaks through water, you see. Rising incidence of storms – check. Rising incidence of drought (paradoxical, but understandable once you get water) – check. Rising forest fires (less rain and less soil moisture) – check. Rising sea levels – check. Melting glaciers – check. In India – arguably one of the most vulnerable countries to this warming – the water voice of the warming climate is hollering loudly. Take the damages from just floods and drought – almost all of us have encountered unusually intense rainfall (a finger print of climate change) this past year.

Figure 2: Damages in India from Floods and Storms (EMDAT database)

And despite the talk, it does not appear as though carbon concentrations will fall any time soon. And with that, warming will continue. In fact, even if emissions were to slow down, warming will continue. Climate Action Tracker, an independent website tracking emission pledges by various countries, places likely warming at well above 2 degrees Celsius by 2100. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the gold standard body for climate information, thinks it very likely the world will warm by about 1.6 degrees Celsius from pre-industrial times by mid-century under the most optimistic scenario – i.e., everyone attains climate nirvana and cuts emissions rapidly.

In a more realistic scenario, warming could very likely exceed 2 degrees Celsius by mid-century. If the water is so volatile at 1 degree Celsius warming, imagine how much more menacing it will be when the warming increases. Take a photo on your phone. Now, go to the editing section and start dialling up the contrast. What the warming climate does is increase contrast in the hydrological cycle: its’s akin to what happens to your photograph when you dial up the contrast. Wet regions will get wetter. Intense downpours like what we’ve seen this past year will become more common. And just as the white regions get whiter in a high contrast image, drier regions will become more parched. Think India’s northwest or parts of Tamil Nadu.

Now you see why water must be a larger part of the conversation.

And then there is us. India’s water is already a high contrast photo. We have one of the most geographically varied, seasonal waters in the world. And yet, we do silly things when we ignore water as we have. For example, we destroy what little water storage we have. Mumbai in the early 19th century had reputedly over 3000 tanks and wells – they are all gone. Chennai, Bengaluru, Madurai, so many other cities had tanks which have morphed into neighbourhoods susceptible to flooding as the climate heats up. In another silly move, we have moved to growing climate-inappropriate crops in one of the driest parts of the country. We have done this by dipping into our water savings – our groundwater. Of course, as expenses continually exceed income, our savings run out, which is what is happening around the country.

ALSO READ | When a Handful of Nutmegs Could Buy You a House or a Ship in Europe

Our local climate warriors espouse the need for India to cut emissions. She should. But that story might unfold easier, if water was part of the narrative, instead of monomania on carbon. There are plenty of examples, but let me take three. First, coal. So many of India’s coal plants are shut down during summers or in the drought because they don’t have enough water to cool themselves. Their utilisation is so low, that they cease to be profitable. These plants in these locations (polluting, unreliable and unprofitable) make a great case of where India can begin weaning herself off coal, thereby lowering emissions.

Second, take solid waste. One helpmate of flooding is the waste that clogs the drains and the rubble and rubbish choking our waterways and water bodies. Now, managing this waste will reduce flooding and help India adapt to a warmer climate. But in doing so, India stands to create hundreds of thousands of jobs, and cut emissions too! How? India’s solid waste is roughly two-third organic – think food waste. Food waste when dumped in landfills rots and releases methane – a powerful greenhouse gas. Managing the food waste will prevent the food waste (one start-up that I have invested in converts this waste into pressurised biogas to replace LPG. At home, we have a tiny biogas plant that powers one stove).

Third, consider forests. Forests play a critical role in smoothening India’s volatile water. You can see their role by their absence in the Kerala floods. Within forests, consider mangroves. Mangroves play a vital role in protecting our coastline. They ameliorate the effect of storm surges, and are thus powerful climate adaptation warriors. Studies have validated their protective role in the 2004 Tsunami and the 1999 Orissa cyclone. They do this while providing a home to an astonishing variety of species and sequestering many times more carbon than other types of tropical forest. Saving mangrove forests (many are disappearing) can help us adapt to a warmer climate by smoothening the ravages of water even while addressing carbon emissions.

Yes, clarity is important in tackling the climate problem. But when the climate has visibly changed, i.e., as new data emerges, the mandate has to take it into account. And the message from the volatile water is, that managing water must form an important part of the narrative.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment