views

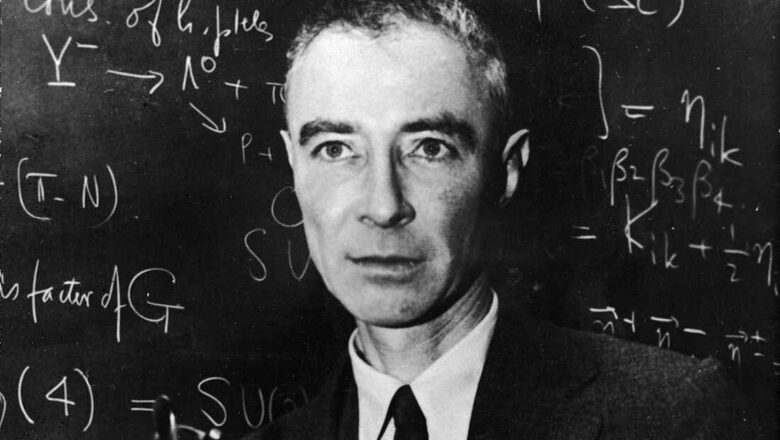

On a cloudless morning in late 1943, a blue-eyed six-feet tall man with close-cropped hair wearing a big-brimmed brown porkpie hat stood somewhere in the middle of Los Alamos in New Mexico, United States, chain-smoking cigarettes and reciting passages from the Bhagavad Gita. The world was at war. The Japanese forces had humbled the nation after bombing Pearl Harbour on 9 December 1941. The threat of the Third Reich dominating Europe was real. America needed to ensure victory and end WW2 faster, saving lives. If WW1 was the chemist’s war, WW2 became a physicist’s war. American theoretical physicist Dr Robert Oppenheimer was in charge of the top-secret $2-billion Manhattan Engineer District. His mission was to lead the scientific effort to devise the ultimate weapon of war — the atomic bomb. It was the highest priority project of WW2.

Born in New York on 22 April 1904, Oppenheimer was the first son born to a family of rich Jewish German immigrants. He had a privileged upbringing and his parent’s opulent apartment on the Upper West Side was filled with an art collection that included three Van Goghs. The musically and intellectually gifted boy studied at Ethical Culture School and entered Harvard in 1922 graduating in just three years. From Harvard, Oppenheimer went to the University of Cambridge, studying under Lord Rutherford, and also worked in atomics with the eminent physicist Dr Max Born.

Five years later these top scientists would encounter another brilliant physicist — Homi J Bhabha of India. Meanwhile, in 1929 Oppenheimer returned to teach theoretical physics at the University of California, Berkeley. He proved to be an exceptional teacher, inspirational and impelling for the youngsters, training an entire generation of world-class physicists. At Berkeley, he was also associated with the quintessential intellectual Arthur W Ryder, a professor of Sanskrit. Ryder had in 1912 recommended Indian revolutionary Har Dayal’s name for a faculty position at Stanford. Ryder gave Oppenheimer private tutorials in Sanskrit every Thursday evening.

With his facility for foreign languages, Oppenheimer was soon enraptured by his Sanskrit studies and the Bhagavad Gita. Motivated by the idea of discharging the duties of one’s station without the thought of fruit the young physicist remained for the rest of his life engaged as a scientist with the physical world, and yet detached from it. In his later years, he listed the Bhagavad Gita as one of the books that shaped his philosophical outlook and gifted copies of the ancient Indian text to his friends. He also named his Chrysler car — ‘Garuda’, after the giant bird god in ancient Indian mythology that ferries Vishnu — the preserver, across the sky.

Oppenheimer’s comprehensive grasp of his professional field saw his reputation grow in American scientific circles. By the early 1940s he came to be known as the man who always gave the right answers before one could even formulate the questions. The inhuman treatment of the Jewish community in Europe by the Nazis had the brilliant nuclear physicist smoldering with fury. At that time Oppenheimer was named as the head of the highly classified ‘Project Y’ — the mission to build the atom bomb. He recruited the best young physicists from American university campuses by only divulging, “I can’t tell you what work we’ll be doing. But I can tell you that it may end this war — and it may end all wars.”

Working in extraordinary secrecy at the hastily built remote desert facility in Los Alamos, New Mexico by 1942 he led a group of super brilliant scientists, some of whom were recipients of the Nobel Prize. Gulping his signature martinis and waving cigarettes he drove himself and skilled scientists at breakneck speed at the field laboratory to get military superiority over the Axis Powers. Oppenheimer knew if his team could not crack the atomic secrets then neither could the Axis powers. Mathematician Charles Crutchfield noted that “Even at Los Alamos, Oppenheimer didn’t talk about weapons or physics. He talked about the mystery of life… He kept quoting the Bhagavad Gita”. Oppenheimer even named the atom bomb test site “Trinity”. It has been inferred by historian Marjorie Bell Chambers that he based it on the Indian divine trinity of Brahma the creator, Vishnu the preserver, and Shiva the destroyer.

At 0530 hours on 16 July 1945, an event at the remote section of the Alamogordo bombing range about 35 miles from the nearest city in New Mexico changed the course of human history. On orders from Oppenheimer and Kenneth Bainbridge, a series of signals were put in motion. There was a tremendous burst of multi-coloured light outshining the sun and expanding over 20 miles before rising to 10,000 feet in a fraction of a second. This was followed shortly thereafter by a 40,000 feet high mushroom cloud, a deep growling roar, and a shockwave that was felt 100 miles away.

The flashlight caused by this man-made gadget was visible from as far as Mars. It announced the birth of the Atomic Age. That morning after the first successful atomic test in history, codenamed the Trinity explosion, humankind discovered atomic fire. A section of the ancient Indian scripture ran through Oppenheimer’s mind. It was Chapter 11, Verse 32 of the Bhagavad Gita, “Shrī-bhagavān uvācha, kālo ’smi loka-kṣhaya-kṛit pravṛiddho, lokān samāhartum iha pravṛittaḥ”

In 1965 in an NBC television documentary, Oppenheimer the emotional and intellectual heart of the atom bomb project recollected: “We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed; a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty, and to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, ‘Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.’ I suppose we all thought that one way or another.”

At the Potsdam conference, American President Harry S Truman received word of the success of the Trinity test and the arrival of a new weapon of unusual destructive force. Next, Japan was given an ultimatum to surrender unconditionally or meet ‘prompt and utter destruction’. Japan ignored the demand for unconditional surrender and Radio Tokyo announced that its forces would continue to fight. Truman decided to end the war swiftly to preserve an estimated million American lives that would be lost in the invasion of Japan.

On 6 August 1945 Colonel Paul Tibbets, flying ace and the commanding officer of ‘Enola Gay’ the B-29 bomber arrived over Japan. His nine-man crew’s adrenaline was up. They were carrying the 8,900-pound uranium atomic bomb named ‘Little Boy’. Tibbets had a clear view of the city of Hiroshima. Flying without escort fighters he carefully guided his four-engined plane to the site of headquarters of Japan’s Secord Army. Morris Jeppson, the electronics expert checked the circuits for the last time. The bomb bays were opened.

Then the countdown began. “10, 9, 8, 7, 6…” Major Freebee pushed a lever in the B-29 and shouted, “Bomb away”. The heavy bomber’s nose lurched up as ‘Little Boy’ departed with its nose down towards the target. The bomb fell for 43 seconds and at 1,890 feet above ground zero it exploded in a nuclear inferno. The fire released by the bomb swallowed the whole city. The citizens of Hiroshima saw something much brighter than the brightness of the sun with temperatures around ten million degrees. 80,000 lives were lost instantly, and an estimated 200,000 human beings died subsequently due to a new scientific invention that used nuclear radiation to massacre on a scale unknown previously. An area of nine square miles in Hiroshima was transformed into an expanse of debris and ruins. From infants to the elderly 140,000 people died by the end of the year.

On that day WW2’s most closely held secret was no longer a secret. For the first time, our planet witnessed the destructive power of an atomic bomb. But Japan still refused to surrender. Washington swiftly ordered a second nuclear strike. Three days after obliterating Hiroshima, at 3:47 a.m. on 9 August, another B-29 lifted off from the Tinian airbase. After eight hours of flying, it dropped the ‘Fat Man’ over the port city of Nagasaki. The shockwave and the atomic heat generated were estimated at 21 kilotons, forty percent greater than that of the Hiroshima bomb. It killed 74,000 people in Nagasaki by the end of 1945. On 11 August 1945, The New York Times ran a banner headline, “JAPAN OFFERS TO SURRENDER” as thousands of ecstatic Americans crowded the Times Square in Manhattan.

Oppenheimer’s leadership at Los Alamos ended with the war and he went on to head the Atomic Energy Commission’s General Advisory Committee. His desk in the President’s Executive Office was across the street from the White House. Acclaimed as “the father of the atomic bomb”, Oppenheimer comprehended he had set a course for a future apocalypse by bestowing upon humanity the possible means for its own annihilation. Unable to deny his moral responsibility the famed scientist told President Truman he had blood on his hands.

In his neo-pacificist avatar, he favoured nuclear energy for electricity generation and opposed nuclear weaponry and nuclear terrorism. In a closed Senate hearing in 1946 Oppenheimer was asked, “whether three or four men couldn’t smuggle units of an atomic bomb into New York and blow up the whole city,” to which he reacted sharply, “Of course it could be done, and people could destroy New York.” The alarmed senator then asked, “What instrument would you use to detect an atomic bomb hidden somewhere in a city?” Oppenheimer joked, “A screwdriver — to open each and every crate or suitcase.”

In the subsequent years, the hero of American science who had been hailed as a genius was shockingly alleged to be a communist based on rumours. In April and May of 1954, after 19 days of secret hearings, Oppenheimer’s security clearance was revoked. The entire scientific community was deeply shocked by the decision. Once the technocrat of a new age for mankind Oppenheimer was branded a traitor. Appointed the Director of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University he lived his life as a broken man.

In this period, he wrote to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru urging him not to sell thorium to the United States in case it would be used for destructive ends. He also received an offer to settle in India from Nehru through his friend Homi Bhabha which he declined. Then his younger brother physicist Frank Oppenheimer, was offered a job by Bhabha at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, but the United States denied him even a passport. Later in January 1966 on receiving the news that Bhabha tragically died in a plane crash in the Alps, Oppenheimer noted, “He will be sorely missed as a scientist”.

Oppenheimer lived in quiet obscurity and was once invited by President John F Kennedy to a White House dinner of Nobel Prize winners in April 1962. He could have been an Einstein as he was nominated three times for a Nobel Prize, (1946, 1951, and 1967) however he never won. In 1963, President Lyndon Johnson gave Oppenheimer the $50,000 tax-free Fermi Award but by then the glory was gone and his days as a scientist were almost over. In his acceptance speech, Oppenheimer said, “I think it is just possible, Mr President, that it has taken some charity and some courage for you to make this award today.”

Oppenheimer was diagnosed with cancer of the throat in mid-1966. After unsuccessful treatments, the globally celebrated physicist lost his battle with the terminal disease at 10:40 pm on 18 February 1967. He was 62. He was survived by his wife, Kitty, and their two children Peter and Toni. Two days later his remains were cremated and a memorial service was held on 25 February at Alexander Hall in Princeton. With visible emotion, the gathering of an estimated 600 people was informed that Oppenheimer had spurned the opportunity to work abroad when he was considered a security risk and had replied with tears in his eyes, “I happen to love this country”.

The New York Times while recognising his genius called him “a classic figure of tragedy”. Japan’s first Nobel prize-winning scientist Dr Hideki Yukawa agreed stating, “Dr Oppenheimer was also the symbol of the tragedy of the modern nuclear scientists” and felt that the government’s actions of stripping him of his security clearance might have shortened his life. Fifty-five years later on 16 December 2022 the US Department of Energy appropriately nullified a 1954 decision to revoke the security clearance, correct the historical record, and honour Dr Oppenheimer’s “profound contributions to our national defence and the scientific enterprise at large.”

Now in 2023, over three-quarters of a century after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, no nuclear weapon has been employed in the last seventy-eight years. Still, there is no assurance in the future. Consequently, the vision of a nuclear-free world must be a global effort. It is time humankind gave peace a chance since a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.

Oppenheimer once said, “Mankind must unite, or we will perish.”

Dr Bhuvan Lall is the biographer of Subhas Chandra Bose and Har Dayal and is the author of India on the World Stage. He can be reached at [email protected]. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment