views

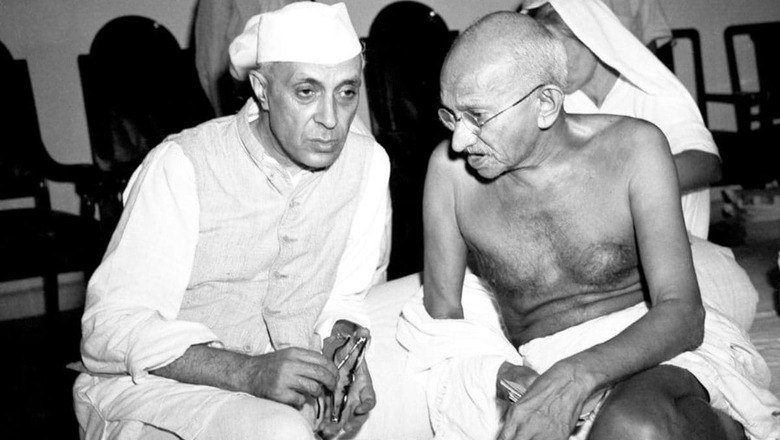

Union Home Minister Amit Shah on Wednesday, while introducing the two Bills — Jammu and Kashmir Reservation (Amendment) Bill, 2023, and Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation (Amendment) Bill, 2023 — in the Lok Sabha, said that Jammu and Kashmir had suffered due to the “blunders” of Jawaharlal Nehru. “Had Jawaharlal Nehru taken the right steps, Pakistan-occupied Kashmir would have been part of India now; it was a historic blunder,” he added.

Explaining the phenomenon further, Shah said that Kashmir suffered due to two blunders. “The first is to declare a ceasefire — when our army was winning, the ceasefire was imposed. If there had been a ceasefire after three days, POK would have been a part of India today… The second is to take our internal issue to the United Nations,” he emphasised.

There is no doubt that India under Nehru committed several blunders that ended up creating the Kashmir imbroglio. But it did not happen in the manner we see it today. Just like the common Pakistani misinformation accusing India of violating the UN Security Council resolution (which is unenforceable till Islamabad first gives up its illegal occupation of POK), there is a hazy understanding of the manner in which India lost a large part of Kashmir to Pakistan in 1947-48.

Amit Shah is right in questioning the Nehru government’s decision of taking the Kashmir issue to the Security Council, and also for holding the Indian Army back when it was poised to take back the occupied area. Looking back, it can be said that Nehru had no option but to knock on the Security Council’s doors. Had Delhi not done that, the Western capitals, prodded by London, would have forced India to come to the UN body. India, given the precarious situation it was in at that time, couldn’t have done anything to thwart the Western move.

Had the West moved the UN wheel first, it would have in all probability invoked a ceasefire under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. Chapter VII of the Charter authorises the Security Council to enforce its decisions by taking “action by air, sea, or land forces as may be necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security”.

The Nehru government moved fast to checkmate this sinister design, and lodged its complaint under Chapter VI of the charter. Under this chapter, the Council can only make recommendations to the parties “with a view to a pacific settlement of the dispute”.

As for the second charge — of holding the Indian Army back when it was poised to win what’s today POK — it’s a fascinating tale of how the Indian leadership had on its own volition pushed itself into a corner. By the time Pakistan launched a war against India in 1947-48, there was very little that the Indian political leadership could have done.

After all, the armies of India and Pakistan at that time were fighting in Kashmir under the overall command of British generals on both sides. General Sir Francis Robert Roy Bucher was commander-in-chief of the Indian Army, while General Douglas Gracey was chief of staff of the Pakistan Army. The two commands were in touch with each other and were being directed by the British authorities in London. It would not be an exaggeration to say that while India and Pakistan were fighting the war in 1947-48, its strategic decisions were being made in London by the British government.

Former foreign secretary Maharaja Krishna Rasgotra recalls in his memoir, A Life in Diplomacy, “When the Pakistan army had fallen back to a line which both Gracey and Roy Bucher thought would be ‘adequate for Pakistan’s overall defence’, the latter, on one pretext or another, just would not use force to change that line. Nehru was keen to eliminate the Poonch bulge but Roy Bucher told him that the Army was fully stretched and there were simply no troops available for the task. For similar reasons we failed to clear the Pakistani forces, commanded by a junior British army officer, from Gilgit and Baltistan, a region of high strategic value which is now being exploited by China for developing a road link to the Persian Gulf.”

India lost a part of Kashmir in 1947-48 because it chose to retain British officers in command of the Indian Army. And it was primarily Nehru’s decision to retain these British officers. Even the dubious role of Lord Mountbatten is not analysed properly, with lazy scholarship ensuring the glowing projection of Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins in Freedom at Midnight remain intact in the Indian psyche.

The Indian leadership led by Nehru failed to comprehend the “big game” being played at the time of Independence. Had it not been the case, the Congress would not have dismissed the Cripps mission proposal, despite repeated requests from Sri Aurobindo to accept it. Nehru & Co. had blinded themselves to see the British machination to “Keep a bit of India” even after leaving the subcontinent — which they did by creating Pakistan.

If Indian leaders had very little comprehension of the ‘big game’ being played at the time of Independence, they complemented the problems for India by carrying on with the old colonial administration even after August 1947. Maybe by refusing the Cripps offer, and thus not being the part of the wartime national government, the Congress leaders missed the opportunity to experience first-hand the governance process, to pinpoint administrative loopholes, and, more importantly, to acclimatise themselves with the process of running the country. Before being given the levers of governance, the last thing these leaders had done was to fight the same system. So, in order to cover up their administrative inexperience, they decided to continue with the old colonial system. Even the English Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, was given an extension.

In a way, Nehru and Gandhi remind us of the two nawabs (of Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khiladi) who were engrossed in a chess game while the British East India Company took over their kingdom, Awadh. They had little inkling of Britain’s sinister plan. Nehru’s blunders didn’t just cost Kashmir dearly. India too was hit badly by his egoistic personality, and obnoxiously ideological and flippantly moralistic worldview.

Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment