views

Should a former Vice President of India enjoy Freedom of Speech, including the right to lambast the direction of the country on international forums? Yes, absolutely. Should someone who has held such high constitutional office at least try to represent all sections of Indian people instead of a single narrow identity? Also yes.

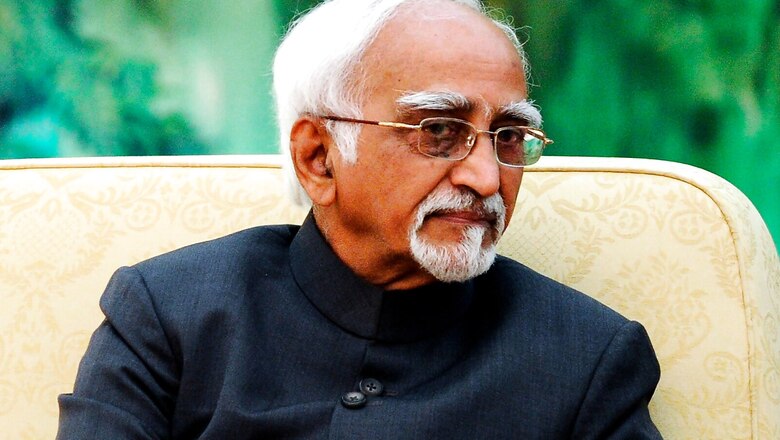

In late 2017, Prime Minister Narendra Modi stood up in Rajya Sabha to say words of farewell to then outgoing Vice President Hamid Ansari. In the space of a few sentences, he summed up Ansari’s career. A diplomat in West Asia, vice-chancellor of Aligarh Muslim University and chairman of the National Commission for Minorities. In other words, always within the same ideology, and working with the same kind of people. His ten years as Vice President, and having to uphold the Constitution every moment, might have been hard on him. It might even have led to some chatpatahat (uneasiness) within. In a few days, however, this responsibility would be lifted off his shoulders, leaving him free to go back to his original ideology. Mr Ansari might be looking forward to that.

I am no expert in nervous laughter, but judging by the reaction to those comments, it seemed that the Prime Minister had struck a raw nerve. Both before and after that day, including his latest comments on a US-based forum on India’s Republic Day, Mr Ansari appears to have proved that this assessment of him was quite correct.

Let us consider what he said at the virtual event:

“In recent years, we have experienced emergence of trends and practices that dispute the well-established principle of civic nationalism and interposes a new and imaginary practice of cultural nationalism… It seeks to present an electoral majority in the guise of a religious majority and monopolise political power. It wants to distinguish citizens on the basis of their faith, give vent to intolerance, insinuate otherness, and promote disquiet and insecurity.”

Beyond the long sentences, three questions come to mind immediately. First, why would the former vice president choose to make these remarks at a forum organised by the Indian American Muslim Council? The other two questions are linked. Is there any merit to Ansari’s claims that India is being torn apart in some way by a new cultural nationalism? And finally, does Mr Ansari’s record in public life represent something better? How did this civic nationalism, as he calls it, promote tolerance, togetherness, peace and sense of security?

It is not hard to imagine what an organisation such as the Indian American Muslim Council (IAMC) stands for. In case somebody missed it, they put it right in the name. It is a sectarian lobbying group with a long history of anti-India activities. The most recent of these, as alleged by the watchdog group DisinfoLab, is buying influence to get India blacklisted by the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF).

Similarly, as noted by Benjamin Baird of Islamist Watch, the executive director of IAMC is one Rasheed Ahmed, who is known to consistently use Hinduphobic “cow urine” jibes against people. Then there are individuals such as Asim Ghafoor, regulars at IAMC events, who have represented people associated with US- and UN-designated terrorist groups. Besides, the social media footprints of other office bearers of the IAMC also suggest high levels of sympathy for both the Indian and Pakistani chapters of the Jamaat-e-Islami.

Above all, one would guess that Ansari, a former diplomat, should suspect that groups such as IAMC feed into a complex ecosystem cultivated by our enemies to damage India’s reputation abroad. Such lobbies pose a threat to people everywhere, but more so to people in democratic countries. This is because our rights such as Freedom of Expression, Freedom of the Press make it hard for governments to act against subversive elements. In the age of the internet, it is even more difficult. So much so that Sweden, often considered to be one of the freest countries in the world, recently set up a Psychological Defense Agency to protect their citizens against subversion from abroad. Why would the former vice president not see the dangers of speaking on a forum organised by a group such as the IAMC?

We do not know his motivations. We can only speculate. Perhaps he failed to perform a basic background check. That would be like the time he spoke at an event in Kerala in 2017, and later admitted that he did not know that it was sponsored by the Popular Front of India (PFI). Perhaps critics of the Modi government go by the cynical logic that ‘enemy of enemy’ is a friend. Maybe there was some other reason. We cannot say.

Now let us come to the substance of Mr Ansari’s charges. What are these emerging trends and practices he refers to? Mr Ansari offers no specifics, no data, not even anecdotes. In an ideal world, therefore, his remarks would be ignored. But we do not live in an ideal world. We live in a world where someone like Hamid Ansari gets to be the vice president of India. And gets to be taken seriously by a wide range of media, academic and civil society voices, all of them making equally vague charges.

Is he referring to the politics of the government at the centre? In that case, I would like to see at least one example of a policy decision by the Modi government that distinguishes between citizens on the basis of their faith. And how do you monopolise political power when there are free and fair elections happening every five years at the central, state and local level? The BJP didn’t even win most of these elections anyway. And one party coming to power while another sits in the opposition, is not called a monopoly. It’s called democracy.

But if you look more carefully, you will notice that the charge is not of monopolising power, but seeking to monopolise it. Similarly, the other charge is not of distinguishing between citizens on the basis of religion, but wanting to do so. In other words, the charges are unfalsifiable by their very nature. Like an anti-vaxxer or anti-EVM conspiracy theory, it seems the details are left to paranoid imagination.

That is the problem with the entire intolerance narrative. It rides on lack of detail, selective outrage and exaggeration. Would 27-year-old Kishan Bharwad, murdered last week in Dhanduka in Gujarat, be considered a victim of intolerance? You wouldn’t know, because the incident was barely reported. Even if it was, the reporting likely referred to the accused being from “another community”. How do we remember 17-year-old Lavanya, forced to commit suicide in Tamil Nadu, also last week?

Would the post-poll violence in Bengal last year be considered an example of monopolising power? We dare not ask, because we would either get “fact-checked” or slapped with charges of “whataboutery”. The principles of fact-checking are simple. In BJP-ruled states, allegations by citizens are used to fact-check the state authorities. In opposition-ruled states, statements by authorities are used to fact-check the citizens. As for whataboutery, two wrongs do not make a right, but apparently some wrongs deserve to be kept out of public view forever.

This makes the intolerance narrative not only unfalsifiable, but also a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you expose a group of citizens to wild conspiracy theories for long enough, you will eventually get them to feel insecure in their own country. That is how Shaheen Bagh happened.

Let us talk about cultural nationalism, because it appears that the former vice president wants to. In the last few years, there has been a bold assertion of Hindu religious identity in the public sphere. Why is this seen as a problem? Did anyone watch the inauguration of Joseph R Biden Jr., the 46th President of the United States? It began with Biden visiting church for a special mass. Then, he took his oath of office on the Bible and proceeded to deliver an inaugural address that read like a sermon from a Catholic religious preacher. Does any of this affect the secular nature of the American government?

And that’s just America, founded on an idea in 1776. In countries of the old world that are now democracies, the embrace of religious identity is even more explicit. In Germany, a major political party (to which Angela Merkel belonged) is called the Christian Democratic Union. The European Court of Human Rights has ruled that the Italian government has the right to place crucifixes in every public school classroom, because the latter is a symbol of Italian culture.

Why is the burden only on India to practice a sterile version of secularism? In order to be considered a modern democracy, why must India give up its ancient soul?

Secularism is a big word, and there are many versions of it. In America, it means that the state does not interfere with religion. In France, it means that no religious symbols are allowed in the public sphere. No visible crucifixes in public schools, and no hijab. Would Mr Ansari get behind a ban on the hijab?

And Indian liberals won’t even get behind the sterile version of secularism. No government in India was ever called “communal” for building a Haj House with public money. The secularism that Indian liberals want is about targeting and keeping out only Hindu religiosity from the public sphere.

And finally, what does the record in public life of the former vice president indicate about his commitment to civic nationalism?

Let’s see. Mr Ansari has been vice-chancellor of Aligarh Muslim University, an entity that somehow manages to qualify both as a minority institution and a public university at the same time. The Supreme Court already ruled that this makes no sense. Not yesterday, but all the way back in 1968. Since then, the minority status of the university has been sustained by a number of constitutionally suspect laws passed by Parliament. Does this violate the spirit of civic nationalism? If Mr Ansari has spoken out against this, I would certainly like to know.

Then, there is Mr Ansari’s tenure as chairperson of the National Commission for Minorities (NCM). The NCM exists purely to treat citizens not as individuals, but as members of a group. As recently as 2018, Mr Ansari backed setting up Sharia courts in every district of the country. Here are his exact words:

“Our law recognises that each community can have own rules. Personal law in India covers marriage, divorce, adoption and inheritance. Each community has a right to practice its own personal law.”

From this, it seems clear that the former vice president sees communities and not citizens as the fundamental units of Indian society. How is this civic nationalism? Does this not insinuate “otherness” between communities? How do you run a modern country without laws being the same for everyone? In the days of the Raj, there would be separate “Hindu paani” and “Muslim paani” at railway stations. The British would have been thrilled with the idea of separate courts for Hindus and Muslims, just like separate electorates.

Ultimately, Mr Ansari’s career is a symptom of the ramshackle nature of Indian secularism and how little it has ever done for the people of India. This includes and, in fact, applies most of all to religious minorities, especially Muslims. The Sachar Committee report found just how few Muslims benefitted from six decades of so-called civic nationalism. The sole beneficiaries appear to be a handful of individuals from privileged upper caste Muslim families with deep roots in the old Congress establishment, appointed to a series of mostly ceremonial positions, for signalling purposes only.

Abhishek Banerjee is a mathematician, columnist and author. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment