views

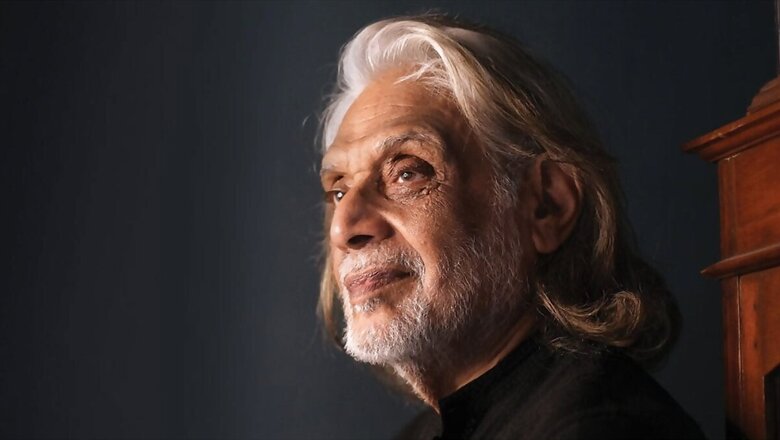

In a world where artists are often confined to one craft, Muzaffar Ali breaks the mold, straddling cinema, fashion, art, and music with the grace of a Nawab and the soul of a Sufi. Hailing from the royal family of Kotwara, Ali’s life reads like an epic novel, one where every chapter is dedicated to preserving and promoting the rich cultural heritage of India, particularly the enchanting traditions of Awadh, his ancestral home.

You probably know him as the mastermind behind the iconic film ‘Umrao Jaan’ (1981), a cinematic gem that captured the elegance, tragedy, and poetic beauty of Lucknow’s Nawabi culture. But Muzaffar Ali is much more than a filmmaker—he’s a cultural alchemist who turns everything he touches into art. His films are known for their lyrical storytelling, visually stunning frames, and an emotional depth that resonates long after the credits roll. If Indian cinema had a soul, Muzaffar Ali would be its poet.

But wait, there’s more! When he’s not behind the camera, Ali dons the hat of a fashion designer, breathing new life into traditional Indian crafts through his label, House of Kotwara. Think of it as a sartorial time machine, where centuries-old embroidery techniques meet contemporary couture. His designs are more than just clothing; they’re a statement of his deep-rooted commitment to India’s cultural legacy—one timeless outfit at a time.

And if you think he stops there, think again. Ali’s connection to Sufi music and spirituality is as deep as the ghazals that waft through the air in his films. He’s not just an admirer of Sufi traditions—he’s their modern-day ambassador. Whether it’s organizing soul-stirring music festivals or producing albums that echo with the mysticism of ancient Sufi poets, Muzaffar Ali has been instrumental in bringing this transcendent art form to a global audience.

In an exclusive interview with News18 Showsha, Ali shared his reflections on the Chitrashaala Film Festival and the role of cinema in preserving rural culture. With the calm wisdom of a storyteller who’s seen it all, he discussed his journey, the characters who’ve danced across his films, and his hopes for the future of Indian cinema.

Chitrashaala Film Festival and its Mission

Q1: What are your views on Chitrashaala Film Festival and its mission? Do you believe such platforms can influence the perception of rural India in mainstream media?

Muzaffar Ali: I think it’s extremely relevant because this way more young people get engaged with those who are working in different pockets of the country. Festivals like this communicate important themes in a creative, dramatic, and attractive format. They are also showcasing the rich wealth of our crafts.

The Role of Cinema in Preserving Rural Culture

In your opinion, how can cinema contribute to preserving and promoting rural culture and heritage, especially in the light of critical social and environmental issues?

Muzaffar Ali: See, the point is that filmmakers today are thinking individuals. They are concerned human beings and are looking at craft in a multidimensional way. As more Indian minds get trained in communication and design, cinema can be a very big tool for the emancipation of the crafts.

Gaman: A Reflection of Personal Experience

Gaman vividly contrasts the bustling city life with the tranquil village life. How much of your personal experience and observation influence the narrative of the film?

Muzaffar Ali: I think, entirely. Because I basically come from a rural environment and I lived and worked in Bombay (now Mumbai). Compared to me, Farooq’s character Ghulam Hasan is underprivileged and dispossessed. So your heart reaches out to him and others like him. You wonder why they have to leave their homes and work in a city. In terms of, I mean, you ask the question, who is sitting under this yellow team in this hot, cold, rainy season? Does he have a heart of stone or not? When these questions come to you, they will ultimately lead you to ideas about what you can do to change something for the better.

Crafting the Character of Ghulam Hassan

Q4: How did you develop the character of Ghulam Hassan? And what aspects of Farooq Shaikh’s performance do you believe brought Ghulam to life?

Muzaffar Ali: I think basically, he was a very understated person. The kind who reaches out to your heart. In retrospect, I didn’t need someone like Amitabh Bachchan for this character. Farooq added to the vulnerability of the character and drew people into the ethos I was trying to shed light on. A protagonist in a film like this has to really touch your heartstrings, you know. If they can’t do that, the story cannot be communicated (kahaani beta hai).

The Poignant Portrayal of Khairun by Smita Patil

Q5: Smita Patil’s portrayal of Khairun is so poignant. How did you approach the depiction of her character, especially her role in highlighting the plight of those left behind in the villages?

Muzaffar Ali: This is exactly what I was trying to portray. And in fact, Smita said, ‘Mera toh koi kaam hi nahi issme.’ And I told her, ‘Nahin, aapka hi kaam hai saara.’ She was to embody the whole angst and waiting that underlines the film. The song ‘Aapki yaad aati rahi raat bhar’ is integral to the film’s emotional landscape.

The Role of Music and Lyrics in Gaman

Q6: How did you choose the music and lyrics, and what role did the songs play in conveying the film’s theme?

Muzaffar Ali: Poetry and music have been a part of my evolutionary instinct. And Gaman was replete with poetry. ‘Seene mein jalan aankhon mein toofan sa kyon hai’ takes you to the heart of the predicament of a migrant. ‘Aapki yaad aati rahi raat bhar’ also takes you into the heart of a woman. Both songs convey the reality of the man and the woman in the city and in the village.”

Gaman’s Timeless Relevance Amidst the Migrant Crisis

Q7: Gaman resonates even today, particularly in the light of the recent migrant crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic. How do you view the ongoing struggles of migrant workers in India, and what changes do you believe are necessary to address such things?

Muzaffar Ali: I think changes are happening gradually. People are getting into portraying themes of social emancipation and rural concerns. Every film potentially has the power to become a part of history and if it cannot be, it has no place in society.

Evolving Perspectives on Gaman’s Themes

Q8: Looking back, how has your perspective on the themes explored in Gaman evolved over the years, especially with the changes in India’s socio-economic landscape?

Muzaffar Ali: I think things have not improved. A taxi driver, for instance, may be facing the same problems and experiencing the same helplessness and exploitation. When I made this film, the underserved citizens were mellow, but now there may be more anger, as they are being driven by the same predicaments.

The Intersection of Poetry and Cinema

Q9: Poetry and music have been an integral part of your life and work. How did your relationship with poetry evolve, especially after the experience with Zooni?

Muzaffar Ali: I don’t write poetry, but I choose it to present a certain kind of trajectory of the character. The character becomes the poem, you know what I mean? So it’s not easy to do that unless you drown yourself in the idiom of the poem. With *Zooni*, it was the same thing. It was like going into a poet’s mind and creating poetry out of her life.

Zooni and the Kashmir Connection

Q10: Speaking of Zooni, it holds a very special place in your heart given the current situation in Kashmir. Do you see any possibility of completing this film in the future?

Muzaffar Ali: Nothing is ever destroyed, you know? So, this also is going to become a part of history. My son has taken it upon himself to restore all the negatives that I have shot, which amounts to about 40,000 feet. And it’s in bachelorette condition, every footage, every frame is there. I want to recreate the ethos and that time in Kashmir, and it will become larger than life. In a way, my journey and my son’s creative path have converged. He was very young when I started *Zooni* and even then he was doing everything from being the clap boy to a lot more.

The Responsibility of Reinterpreting Traditional Themes

Q11: How do you feel about modern filmmakers like your son reinterpreting traditional themes? Do you believe this helps in preserving cultural heritage, or does it risk altering it?

Muzaffar Ali: It’s a very big responsibility to present a slice of reality, of a certain time in history. And there’s a very special kind of discipline called production design which is lacking in India. Production design actually has to have the prime focus. Makers try to do this themselves. When they go out of focus, they go beyond their brief. So, they don’t know what the hell they are doing. You need to create that kind of discipline in India.

Collaboration with Contemporary Filmmakers

Q12: If given an opportunity, would you be interested in collaborating with Sanjay Leela Bhansali on a project? If so, what kind of story or theme would you like?

Muzaffar Ali: He’s in his own world, I’m in my own world. Everybody knows what his world is and what my world is. I create a world where people are happy, and I too am very happy in my world.

The Evolution of Indian Cinema

Q13: How do you perceive the evolution of Indian cinema over the decades? What do you think are the most significant changes that have occurred, either good or bad?

Muzaffar Ali: The good part is that some new energy is coming in the young minds regarding how to tell a story. The challenge, however, lies in putting across ideas for the public. Right now, that expression is very controlled. So, more growth should happen. At the moment, it’s all stifled.

—

In short, Muzaffar Ali is a renaissance man who effortlessly blends tradition with modernity, leaving a lasting impression on everything he touches. Whether he’s crafting a film, designing a piece of couture, or curating a Sufi music experience, Ali’s work transcends artistic boundaries. His contributions have not only enriched the cultural tapestry of India but have also left an indelible mark on the global arts community. With every project, he continues to inspire and influence generations of artists and cultural aficionados worldwide.

Muzaffar Ali isn’t just creating art—he’s creating a legacy.

Comments

0 comment