views

One of them looks at you directly: frank, clear-eyed and unblinking.

Another, his helmet a bit askew, wears a grim, dazed expression.

These and other faces of the American wars fought since September 11, 2001 are now on display in a Washington museum, lending a human dimension to faraway conflicts.

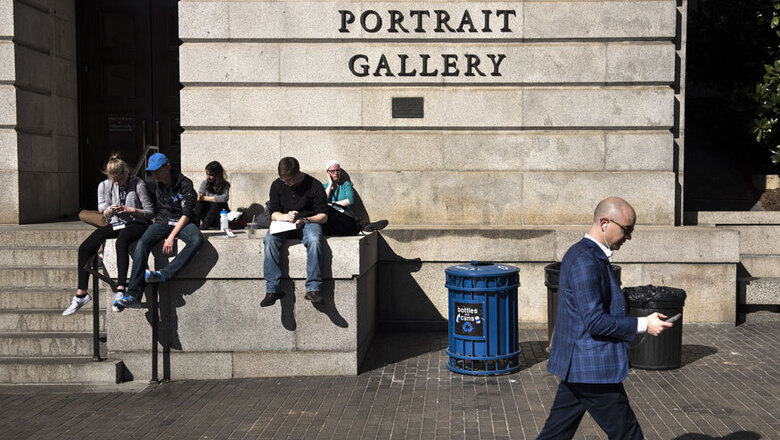

By an accident of the calendar, the exhibit "The Face of Battle: Americans at War, 9/11 to Now," at the National Portrait Gallery until January 28, 2018, opened Friday -- hours after the United States launched its first military strike against the Syrian government, potentially opening a new battle front for the United States.

If the period covered by the exhibit begins with the United States opening its "war on terror" following the terror attacks of 2001, it has more to do with the relentless pace of these conflicts than with their intrinsic nature.

The idea for the show originated with the observation by its planners that the American soldier had been transformed in recent years into a "marketing product," omnipresent in television ads and product placements, a symbol, in their eyes, of the "normalization" of the GI.

Six artists working in varied media -- photography, painting, sketches and videos -- were chosen to tell the story of "the emotional and psychological impact and consequences of modern warfare," said Kim Sajet, director of the portrait gallery, during a preview for reporters.

- 'Personalizing' war stories -

"This is not intended to express the total experience of wartime," she said. But individual stories -- "encounters" with individual soldiers -- can create a sense of empathy in visitors, she said.

War photographer Louie Palu wanted to create exactly that sort of encounter for museum visitors. What is striking about his photos is the power of the expressions on the faces of soldiers he met in the Afghan provinces of Kandahar and Helmand between 2006 and 2010.

"There are two kinds of photographs -- there are the ones that you look into, and then there are photographs that look out at you," said Palu, who is Canadian. "You have to go and look in someone's eyes. I purposely don't have them with any guns. It's just a person."

His aim was not to take action shots, but to personalize the soldiers' stories, portraying them in natural poses away from the front.

Some wear haggard expressions, with the unfocused gaze of bone-tired fighters -- the "thousand-yard stare."

This fragility persists when these weary warriors return home. "They are our neighbors, sisters, brothers," Palu said. "They're part of our society, and some of them are having a hard time."

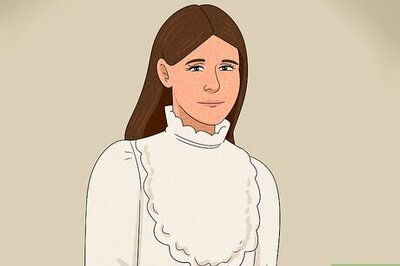

Another room features a huge three-panel fresco comprising 1,500 pencil sketches, each about three by four inches (7 centimeters by 10 centimeters). Each one represents a soldier who died in combat, including his or her name, date of birth, and date of death.

Artist Emily Prince had heard news reports about the mounting numbers of war dead, but she was left wanting to know more. "I wanted to know who the individuals were behind the numbers," said Prince, a librarian.

- The poignancy of absence -

So, after sifting through obituaries posted on a specialized web site, she began in 2004 to sketch the faces of the war dead. To date she has done more than 5,200.

"This is about humanizing these numbers," she said.

Another photographer, Stacy Pearsall, had a different approach. "I wanted to focus on moments of camaraderie" and on soldiers' daily lives, said Pearsall, who joined the US Air Force at the age of 17, rising to the rank of staff sergeant.

In one photo, a military dog reaches out a paw to a weary but gently smiling soldier; in another, two soldiers play around on a seesaw, while in yet a third photo, a serviceman firmly grips a baseball bat, preparing to swing at a stone serving as a ball.

"For me," said Pearsall, who was seriously wounded in action in Iraq, "the most important story was to remind the viewers that these soldiers were men and women."

Paradoxically, some of the most poignant images are those in which soldiers are absent. They include photos by Ashley Gilbertson, who photographed empty rooms -- beds neatly made, everything arranged with military precision -- in the homes of men and women who lost their lives in Afghanistan or Iraq.

The pictures testify to the youth of the fallen.

In the room, for example, of Konstantin Menz, who died aged 22, everything is in order: the Axe deodorant, the toy soldier... everything neatly in its place except for a foam ball and a white teddy bear.

Comments

0 comment