views

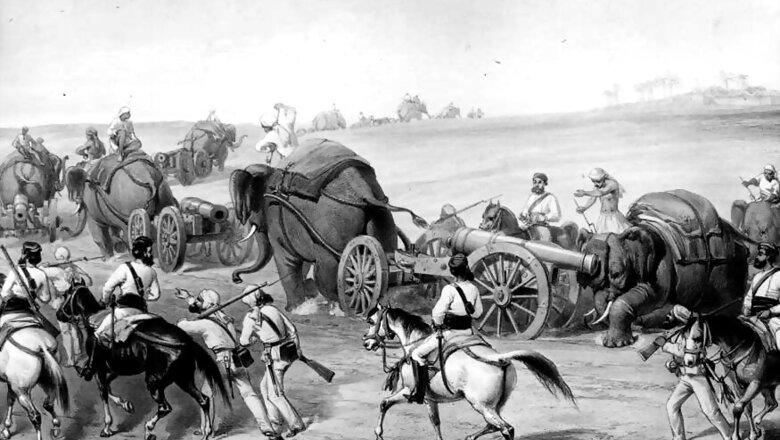

Meerut: The year was 1857 and it was past 5 pm at Meerut’s Sadar Bazaar. Just like any other day, British men were in the market to buy beer to beat the harsh Meerut heat. Very soon, a large group of Sepoys marched towards the Bazaar, and started beating the British with their bare hands. India’s first War of Independence had begun.

“Many people don’t know that Baker’s Street was where the first War of Independence started,” said 76-year-old Atul Kumar, one of the oldest residents of the street in Sadar Bazaar whose family, he claims, has lived on this street for nine generations.

News18 spoke to Dr Amit Pathak, a Meerut-based historian and author of ‘1857: A living history’, who has spent years collecting documents, trying to piece together the sequence of events on May 10 that year.

“Immediately after the violence began, some Sepoys moved to Parade Ground, now known as Meerut Race Club. Their aim was to take control of weapons and prepare for war,” said Pathak.

May 10 rendered many British men dead. “Not far from Sadar Bazaar is St. John’s Cemetery in Meerut Cantt area. There are hundreds of graves here, most of them from the 19th Century. But there are nine graves here that tell very interesting stories. The date on all these graves is May 10, 1857 – the day of the uprising,” he said.

The first death of the uprising

“This is perhaps the most important of all the graves,” said Pathak.

Col. John Finnis was the first British Officer to die in the uprising. In the mayhem, Col. Finnis, commandant of the 11th Native Infantry, managed to control men of his unit. He then rode towards the 20th Native Infantry to control them as well.

“The sepoys of this other regiment were not ready to listen to his requests and did not pay heed to his commands. When he was returning towards his own regiment, the first shot of the rebellion was fired. It hit Col. Finnis’s horse and he fell down. When two men tried to pick him up, he gave his last order before he, too, was shot. Inform the General – he shouted in his last order,” said Pathak

The man who caused the ‘mutiny’

There are many causes ascribed to the uprising. From 100 years of misrule under the East India Company rule to the deteriorating relationship between officers and troops. But the proverbial match that lit the haystack were the cartridges laced with cow and pig fat, which brought Pathak to the grave of Col. Carmaical Smith.

“After the carnage began, the sepoys made their way to Col. Smith’s house and killed him. He was commandant of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry. He was the man responsible for the mutiny. On April 24, it was Col. Smith who had organized firing practice and ordered Indian troops to bite the controversial cartridges. When 85 Sepoys refused, they were rounded up at a ground and publically humiliated. For Indian soldiers, humiliation was worse than death. During the uprising, most of the Sepoys’ anger was directed against Col. Smith.”

The killing of Mrs. Chambers

The British response to the uprising was brutal.

So brutal were reports of her death that for Britons, she became a symbol of British sacrifice. “Mrs. Chambers was alone at home when her servants informed her that an enraged mob was making their way to her bungalow,” said Pathak, “They (servants) managed to hide her from the mob. After the mob left, Mrs. Chambers was trying to escape. She ran into a local butcher who hacked her to death with a meat cleaver. This outraged the British so much that Mrs. Chamber’s death became a rallying cry for them. Whenever British officers needed to motivate their troops, they would shout – These are the killers of Mrs. Chambers!”

Luisa Sophia – the British woman in a burkha

“If you see this gravestone,” says Pathak, “a husband and wife have been buried together. Donald Macdonald, a British officer, was killed in the parade ground shortly after Col. Finnis was shot dead. Luisa Sophia, his wife, was at home when her servants whisked her away. The servants clad her in a veil – a burkha, along with other women of their house. When they were escaping, they were intercepted by some locals. They started lifting the veils of all the women with the tip of their swords. When they finally saw Luisa Sophia, they asked her to identify herself. She simply responded by saying – Hum hain (It is I). There was an unmistakable English accent in the way she spoke those two Urdu words. They then killed her on the spot. Her children, however, survived and grew up in England.”

Comments

0 comment