views

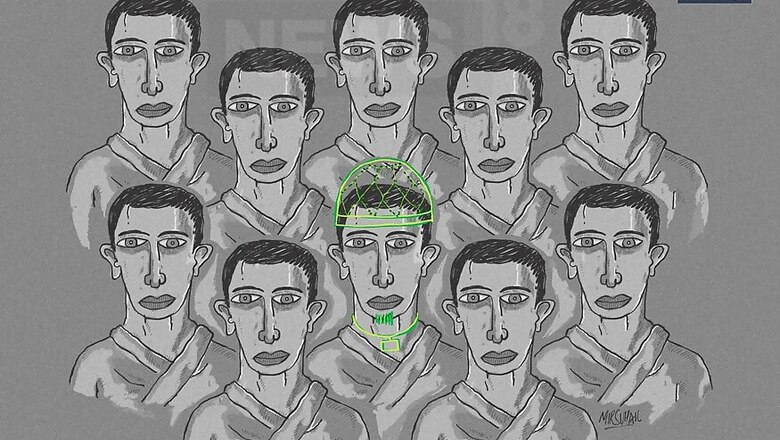

New Delhi: The year is 2008. A series of five low-intensity blasts bring the national capital to its knees, killing nearly 30 people. Six days later, on September 19, two young men are killed in a swift encounter with the police in Delhi’s Jamia Nagar – a Muslim majority neighbourhood.

Suddenly, the suburb famous for its street food becomes the ‘hub of terrorists’ for the media. What follows is a witch-hunt against Muslim boys in the area. The Delhi Police arrests many.

Jamia Millia Islamia University, students and teachers alike, erupt in protests. People question the encounter that took place. “It was fake,” the word spreads.

Amid all this, a young boy, like many others, starts questioning all that is happening around him. The next few months and questions he asked himself become the central theme of the book he authors 10 years later.

As the evening started to set in on a warm Saturday, Neyaz Farooque, author of An Ordinary Man’s Guide to Radicalism, sat cross-legged outside a small café in Delhi’s New Friends Colony – a mile away from the place where it all started for him: Jamia Nagar.

Neyaz, in his early thirties, hardly comes across as an author of a book that flips the tired narrative of victimisation on its head. As he tucks his brown leather bag to his bosom, the journalist in him becomes rather evident as he asks, “How bad is the situation in Kashmir?”

That, perhaps, is the reason his book – heavy with spare and profound prose – is more of a journalistic work going into layers of recasting a question: Is Muslim identity in India driven by hatred, blatant stereotyping or just complete ignorance?

A vivid account of experiences and coming of age while growing up in a Muslim ‘ghetto’, An Ordinary Man’s Guide to Radicalism is a raw, honest and intricate look into the lives of ordinary Muslims from an insider’s lens and the ever-so permanent outsider’s perspective.

Characters rendered with depth and specificity, the stories center on simple chores and big, small decisions of life.

Indeed, suspicion, unease and tragedy pervade these accounts but Neyaz reaches deep into his past, identifying the moments and encounters that helped transform a young boy into a passionate storyteller whose life, more often than not, revolves around his core identity: a Muslim.

Neyaz is an alumnus of Jamia Millia Islamia, a minority institute that is facing opposition from the ruling government for being awarded the ‘religious minority status’. When the Batla house encounter happened, he and his friends – all students at that time – were caught amid the storm. Night raids and constant suspicion by the authorities resulted in a sudden realisation that being a Muslim had its drawbacks. Yet, the idea of writing this book stemmed from what Neyaz said was “unfortunate media reportage”.

“Those were difficult times. The reportage around Batla house encounter was so skewed that words like alleged or accused weren’t even mentioned. Contrary to the facts, sweeping generalisations were made that Jamia Nagar is the hotbed of SIMI terrorists; that people here are terrorist sympathisers. We didn’t feel safe at all,” Neyaz said.

But there was more to it that worried Neyaz at the time.

In his early twenties those days, Neyaz closely observed what the police, authorities and the media was doing. He felt that there was a larger scheme of things at play here.

“What struck me the most was, why the two boys, who were killed, didn’t go into hiding after the blasts. Everyone knew that police had intensified the raids. After the boys were killed, police said ‘they were living like normal humans beings’. That scared me the most. It was not about terror anymore. It was turning anti-Muslim,” Neyaz said.

That’s when the college student thought of becoming a journalist and telling stories which he felt needed to be told.

Ten years later, Neyaz, who took almost four years to complete the book, believes that this account of him and the people he has been with, both personal and political, is in a context of a tipping point — a threshold of patience.

“Whatever you see right now; the Muslim bashing, the hate, the suspicion, it all is the culmination of events that happened after the 80’s. The demolition of Babri, the riots in North India, and the discrimination — there was a need for some sort of manifestation. Somebody had to write about what it means for a common Muslim,” Neyaz argues.

When Neyaz began to write the book, he wanted to get away from Jamia Nagar and move to a different place to look at the issue from an outsider’s perspective. He found a flat in Delhi’s Sukhdev Vihar but was immediately shown the door after the owners came to know that he was a Muslim.

“It’s natural. If you look at the geography of the city you’ll see a majority of the Muslims living in the periphery of the city. That translates into people’s thinking as well. Muslims are at the periphery of their minds as well,” he said.

With regard to specific issues that are fore-fronted in the book – trauma, dissociation in victims and perpetrators, the issue of voice, effects of emigration and the diaspora, centrality of context, and the dynamics of being treated as the ‘other’ – Neyaz chronicles what it means to live in a ‘ghetto’.

“Living in a ghetto is not always a choice,” he said. “We (Muslims) are forced to live like that.”

Neyaz has also been successful in highlighting some of the disconcerting repercussions of pervasive Islamophobic rhetoric that one finds in popular culture. “That,” he believes, “was only possible because he – unlike most memoirs – isn’t the star of the story but just a vehicle.”

As the book deals with the identity issue of Muslims at large, Neyaz’s writing questions the de facto criminalisation of certain types of signifiers of Islamic identity, aided and abetted by certain narrative manoeuvres such as references to beards, skull caps, etc.

“There are a lot of assumptions when it comes to Muslims in India. So much so, that it is in your face most of the time. Our parents have lived with this guilt that they were the reason behind the partition. Now, this generation is being told to show more patriotism. Shouldn’t these issues be talked about?” Neyaz questions.

While Neyaz’s book questions conventional perceptions and proposes another mode of enquiry, many who read it believe that the writing is a “grand proclamations of sort, not a commitment to emancipation.”

A journalist, who is a Muslim and has read the book, said, “While the writing is insightful and evocative but a lament for times past, the neo-liberalism and nostalgia for a form of life that may never exist for us (Muslims) seems too far-fetched.”

One could agree that this form of writing a memoir, a call for neo-liberalism (or liberalism) can restrain and limit the view but Neyaz offers a different perspective.

“We (Muslims) need to be liberal in our approach. I am not saying we haven’t been. We are as liberal as anybody could be. Yet, we are also as conservative as anybody could be. There is a need to look inwards, too,” Neyaz said.

This, perhaps, could be the reason that Neyaz’s book has garnered positive response from the youth, mostly in small towns, while the ‘elite Muslims’, as Neyaz likes to refer to them, have had their reservations.

“Many Muslims who form the elite league had problems with my book, partly due to their own incompetence to tell the stories that matter. It’s time we tell our own stories,” he said.

Neyaz’s concerns seem plausible. Not much literature has been out like ‘An Ordinary Man’s Guide to Radicalism’, which wrestles with psychological and political space, between a recent past and an intensified present. Maybe that’s why the book becomes all the more important to understand resolutely complex lives of Muslims in India.

In the prologue of the book, Neyaz writes: “My own story is one of a kid who came to Delhi with many hopes; of a young man who lost his way; and then, if I might say so, of someone like you.

Will you read my story?”

Perhaps, it’s time we should.

Comments

0 comment