views

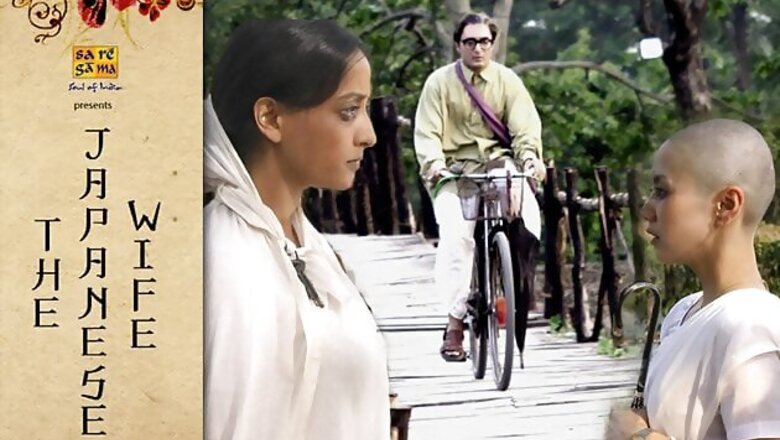

The boundaries of love are amorphous and ambivalent. Love, in its varied manifestations, has a multi-channeled focus - though our narrow vision looks at it within strict socially defined frameworks. Aparna Sen’s new film The Japanese Wife draws attention to this amorphous quality of love, of relationships and of marriage.

The film, based on a short story by Kunal Basu is about love that transcends these socially defined boundaries to show how ‘marriage’ can exist beyond rituals, and reach out beyond caste, class, creed, culture, language and geography.

Snehamoy (Rahul Bose), who teaches arithmetic at school in a village in the Sundarbans, gets married to his Japanese pen friend Miyagi (Chigasu Takaku). The ‘marriage’ consists of a silver ring that Miyagi sends him, and a pair of white conch-shell bangles he sends her. Their principal way of communication is through letters – 637 of them spread over 17 years.

Snehamoy takes up tuitions to fund his postal expenses. The letters are filled with mistakes in English grammar, recited in their soft, child-like voiceovers. The innocence of their content spells out a delicate love story.

Four telephone calls are also incomplete between the two lovers. At Gosaba, the nearest town across the river Matla, signals are weak. Other ways of contact are through gifts – simple ones like a yellow sari and a blouse that Snehamoy’s modest means will allow, and lots of souvenirs from Miyagi.

The film opens with a 40-plus Snehamoy, his hair streaked in white, looking back on memories of his marriage and his wife who he has never met. The scene cuts to a huge carton covered with colourful labels and Snehamoy’s name and address printed in bold black in one corner, arriving first on a boat, then in a van and then to his house, chased by curious village kids. It is a present from Miyagi on their 15th wedding anniversary. Filled with colourful Japanese kites of all shapes and sizes, the carton is metaphor of this sweet, colourful and unique love story.

The Matla River is an important character, as much in its quietude as in its violence. It swallowed Snehamoy’s parents when he was little. Snehamoy often retires to the bottom of a boat tied to its shore, sometimes to masturbate, mostly to reflect on the love of his life – Miyagi. The river’s ferry service closes down when there is a ravaging storm and the sky is filled up with the jagged edges of dangerous lightning.

Miyagi’s letters stop coming. Medicine cannot be bought to cure Senhamoy’s pneumonia. A night of getting wet in the showering thunder and rain snuffs out Snehamoy’s life.

Miyagi, draped in the customary white sari and blouse, arrives on a boat. Snehamoy had told her that widows wear white. But she still has the white conch shell bangles on her wrists. Snehamoy had not told her that a widow must take them off when her husband dies. Miyagi's head is shorn of hair, probably because she had heard from her husband that depending on the degree of a wife’s love for her husband, a wife shaved off her hair when the husband died.

The characters, from Snehamoy through the Ayurvedic doctor who insists on feeling the pulse of his patient, to Sandhya’s (Raima Sen) little son are fleshed out more with love and care than crafted out of a dry film script.

Rahul as Snehamoy deconstructs himself to slip under the skin of an introvert, shy and reclusive arithmetic teacher who suddenly discovers life and vigour in a kite fight triggered on by a small boy. This is Rahul's career-best film till date.

Ditto for Moushumi Chatterjee as Mashi. She ages from a young, married woman to a mature, simple widow, speaking twenty to the dozen in her dokhno accent, her talkative nature relieving the silence of Snehamoy and Sandhya.

Raima Sen emotes more with her face, her attitude, and her eyes than through speech. Chigasu Takaku’s soft, lisping English in the voiceover is complemented by her delicate, fragile, sad and lonely looks, especially in her home setting.

The kite fight highlights also a colourful and fun-filled relief in an otherwise sad film.

Cinematographer Anoy Goswami and art director Gautam Basu invest the film with rich visuals, both indoors and on location. Sagar Desai’s background score is soft and subtle to fit into the delicate, romantic mood of the story.

If you are looking for logic, there is none. Aparna Sen weaves a beautiful tale of love through a little fantasy, a lot of innocence and some exuberance. The Japanese Wife is a tribute to love in its purest form and a tribute to the lost art of writing letters as well.Critic: Shoma A. Chatterji

Comments

0 comment