views

X

Research source

That being said, open-ended questions require as much effort to write as they do to answer. Whether you’re getting ready for an academic discussion, preparing to interview someone, or developing a survey for sales or market research, keep in mind that your questions should ideally spark reflection, discussion, and new ideas from your respondents.

Determining a Specific Purpose

Prepare open-ended questions based on reading for class discussions. If you’re a high school, college, or graduate student, you may be asked to come up with questions based on assigned reading material to prepare for in-class discussions. The best kinds of questions to prepare in these cases are open-ended, because the possibility of multiple potential correct answers leads to sustained, productive conversations. Take notes on potential questions as you read. While you read the source material for your class discussion, write down broad, big-picture questions about what you’re reading. If you have identified or been given a purpose for reading, use it to guide the questions that you might ask. Later, you can use these notes to help write more polished, final open-ended questions. If you have trouble coming up with specific questions while reading, underline or circle portions of the text that seem important, confusing, or connected to your purpose for reading. You can return to these later as starting points for your written open-ended questions.

Add open-ended questions to market research surveys to gain new insights. If you own or are employed by a business, you might periodically send surveys to current and potential customers to evaluate how satisfied they are with your product or service, or whether they would be interested in trying new or similar versions. In these situations, open-ended questions can yield feedback and ideas that you might not have otherwise expected, and can be helpful tools for improving your enterprise. For example, instead of asking: “Were you satisfied with your experience?” You could try something like: “What about your experience did you find most satisfying, and what about it did you find frustrating or difficult?” Instead of simply giving a “yes” or “no” answer, your respondents will give you specific information, and possibly new ideas for improving your product or service. However, if you’re looking for simpler, more quantitative data, it might be easier to rely on multiple-choice, yes-no, or true-false questions, all of which are closed-ended. For example, if you’re trying to find out which gelato flavor was the most popular at your shop this month, it would be easier to ask a closed-ended question about which the respondent purchased most frequently, and then list all available flavors as potential answers.

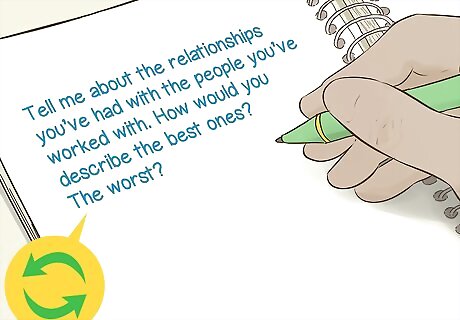

Use open-ended interview questions to thoroughly screen a potential job candidate. If you’re hiring someone for their services and expertise, you’ll need to interview them beforehand to ensure that they are suited for the job. Asking potential employees open-ended questions will help you learn more about your candidate than their skills and accomplishments, giving you crucial insight into their personality, behavior, and character. Then, you can assess whether your work relationship with the candidate would be productive and pleasant, and not just whether they can get the job done. Examples of effective open-ended questions to ask in an employment interview include: “In a previous job, have you ever made a mistake that you had to discuss with your employer? How did you handle the situation?” or “When you’re very busy, how do you deal with stress?”

Prepare open-ended questions for journalistic interviews to ensure thorough responses. If you’re interviewing somebody for a magazine, a newspaper, or a blog, asking open-ended questions is a great way to encourage your subject to explain their answers fully, instead of just rattling off their own personal talking points. This way, when you sit down to write you’re article, you’ll have substantive information about the interviewee’s opinions and policies, and not just canned statements or buzzwords. This strategy can be especially useful when interviewing a candidates for public office, who are often more concerned with pushing their own platform than with giving thorough, honest answers. Closed-ended questions allow interviewees like these to halt the conversation with a “Yes, but…” or “No, but…” response, and then redirect it towards their own agenda.

Structuring Effective Questions

Begin your question with “how,” “why,” or “what.” As you begin writing your questions, start them with words that could prompt multiple possible answers. Questions that open with more specific words, such as “which” or “when,” often have a single correct answer. Instead, your question should encourage debate and discussion of multiple ideas. This isn’t a hard-and-fast rule – you can write a closed-ended question with any leading word. For example, “What color shirt was she wearing?” is decidedly a closed-ended question.

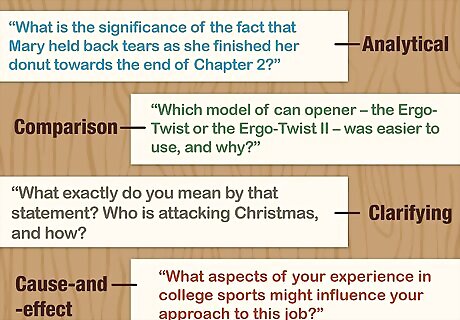

Create questions that analyze, compare, clarify, or explore cause and effect. Using any notes you’ve taken as a resource, come up with questions that look for reasons behind events or statements made, seek to clarify confusing points, or investigate key differences. Questions of these types tend to prompt multiple answers and lead to fruitful discussion. Analytical or meaning-driven questions might ask why a character in a literary text is behaving a certain way, what the importance of a particular concept is, or what the meaning of a scene or image might be. In a class discussion about a novel, you might ask: “What is the significance of the fact that Mary held back tears as she finished her donut towards the end of Chapter 2?” Comparison questions might ask about similarities or differences between character perspectives, or ask the respondent to compare and contrast two different methods or ideas. For example, in a marketing survey, you could ask, “Which model of can opener – the Ergo-Twist or the Ergo-Twist II – was easier to use, and why?" Clarifying questions might ask what the meaning of a complicated idea or an unclear term might be. For instance, if you’re interviewing someone who keeps bringing up “the war on Christmas,” you might ask them, “What exactly do you mean by that statement? Who is attacking Christmas, and how?” Cause-and-effect questions might ask why a character is displaying an emotion in a particular situation, or what connections might exist between two different ideas. An example of a cause-and-effect question that you might ask in an interview could be: “What aspects of your experience in college sports might influence your approach to this job?”

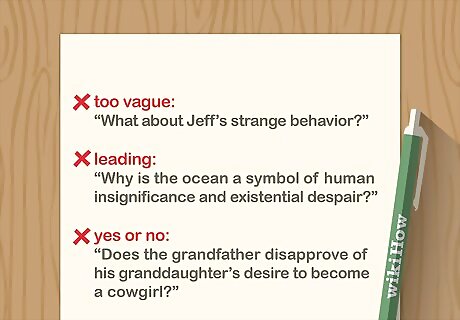

Avoid questions that are vague, leading, or answerable in one word. If a question is generally unclear, seems to be fishing for a particular answer, or can be answered with a word like “yes” or “no,” it won’t lead to a sustained or productive discussion. An example of an excessively vague question might be “What about Jeff’s strange behavior?” (Well, what about it?) A leading question hints at the expected answer, thus making it difficult for students who have different ideas to speak up. An example might be: “Why is the ocean a symbol of human insignificance and existential despair?” An example of a yes or no question would be: “Does the grandfather disapprove of his granddaughter’s desire to become a cowgirl?”

Avoid questions with limited possible answers. If, for example, you give respondents a multiple-choice survey question with a limited set of responses, they might not be able to give you the answer that feels truest to them. When creating open-ended questions, construct them so that respondents can express themselves freely. They should not be limited to a single correct response, or even a limited set of possible responses – that would be a closed-ended question. This could mean offering survey respondents a text box to type or write their answers in, rather than bubbles to fill in. In a conversational setting, like a journalistic interview, this means avoiding giving your subject potential answers when you pose the question. For example, instead of asking, “Would you prioritize an aggressive overhaul of public transportation or the increased use of alternative fuels?” ask a question like: “What strategies would you prioritize to make our city more energy-efficient?”

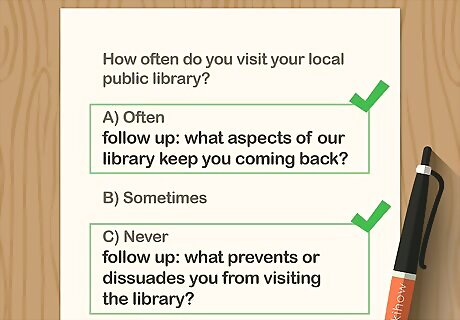

Follow up closed-ended questions with open-ended questions. To encourage more elaborate, complete responses, you can ask an open-ended follow-up question directly after closed-ended survey, interview, or discussion questions. This way, you can gain basic, essential information from a question with limited responses, but also find out the “why” behind the answer. For example, if you ask a multiple-choice question like “How often do you visit your local public library? A) Often, B) Sometimes, or C) Never,” you could follow it up with questions like: “If you chose A, what aspects of our library keep you coming back?” or “If you chose C, what prevents or dissuades you from visiting the library?”

Check over your questions to make sure that they’re open-ended. When you’re done writing your questions, go over each one and think about how it might be answered. If you can imagine a few possible long, in-depth responses, your question is good to go. If it heavily favors a particular response or can be answered in one word, revise it so it’s more likely to lead to a longer discussion or a more thorough answer.

Comments

0 comment