views

Understanding Some Basic Fiction Mistakes

Don’t start too slow. While some writers do start very slowly and let their stories build up dramatic tension over time, this requires a level of practice and skill that most beginning writers just haven’t developed yet. Fiction depends on conflict, and that needs to be set up as early as possible. Famous short story writer Kurt Vonnegut once gave this tip: “To heck with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.” Hopefully, cockroaches won’t eat your story, but if you have several initial chapters of ordinary people doing ordinary things without any challenges or problems present, readers may not see why they’re supposed to care. For example, in the first chapter of Stephenie Meyer’s massively popular novel Twilight, all of the basic conflicts are established: Bella Swan, the heroine, has moved to a new place where she doesn’t feel comfortable or know anyone, and she meets the mysterious hero, Edward Cullen, who makes her uncomfortable but whom she also feels drawn to. This conflict, that she’s interested in a person she’s also confused by, sets the rest of the action in motion. One of the inspirations for Twilight, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, also sets up a central problem within the first chapter: a new, eligible bachelor has moved into town and the heroine’s mother is desperate to set up one of her daughters with him because the family is poor and needs to marry off the daughters for them to have a hope of comfort in their later lives. The problem of finding husbands for these women forms a major part of the novel, as does the challenge of the mother’s troublesome meddling.

Establish the stakes early. To be engaging, your fiction needs clear stakes for its characters. These don’t have to be world-shattering, but they do need to feel important to the characters. Vonnegut once said that “Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.” The main character needs to want something and be afraid (for good reasons) that they won’t get it. Stories that don’t have clear stakes are very hard for readers to engage with. For example, whether or not a heroine gets to be in a relationship with the person she loves probably isn’t going to be the end of the world for everyone else, but it is something that should be very important for the character. Sometimes, the stakes literally are the end of the world, such as in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings series, in which the characters’ failure to destroy the One Ring will result in the destruction of Middle Earth by evil. These types of stakes are usually best reserved for fantasy and epics.

Avoid exposition-heavy dialogue. Dialogue needs to sound natural for the characters speaking it. Think about it: When was the last time that you gave your entire backstory in a speech to someone you’d just met? Or recapped everything that happened in a previous encounter, in detail, in a direct address to a friend? Don’t have your characters do that, either. This type of expository dialogue is sometimes called “info-logue.” While it may be an easy way to give the reader background information, it tends to sound unnatural unless it is handled very carefully. Using info-logue is a common mistake among beginning writers. For example, Charlaine Harris’s popular Sookie Stackhouse novels have a bad tendency to spend the first few chapters of every book “catching up” on everything that happened in previous books. The narrator will also frequently drop in to explicitly remind the reader of who a character is and what their function is. This can get in the way of smooth storytelling and distract the reader from engaging with the characters. There are exceptions to this rule. For example, if you have a mentor-mentee relationship between characters, you may be able to include more exposition in their interactions. A good example of this is the relationship between Haymitch Abernathy and his mentees Katniss Everdeen and Peeta Mellark in Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games series. Haymitch can explain some of the rules of the Hunger Games and how to do well in the competition in his dialogue because that’s explicitly his job. Even in situations such as this, though, don’t overload dialogue with factual world-building.

Don’t be too predictable. While a lot of fiction proceeds along very familiar lines -- consider how many stories are about heroic quests or 2 people who initially hate each other but learn to love each other -- you don’t want to lapse into formulaic storytelling. If your reader can predict everything that’s going to happen, they won’t care about finishing your story. For example, you could have a romance novel in which it’s hard to see how the characters will end up happily ever after because of the situations they’re in or their personality flaws. The surprise for readers will be how things do end up working out in the end, despite all appearances to the contrary. Don’t, however, fall for the “it was all a dream” trick. Ending twists that negate everything about the story that preceded them very rarely work out well, as readers generally feel as though they’ve been deceived or tricked.

Show, don’t tell. This is one of the cardinal rules in fiction, and it’s also one that frequently gets ignored. Showing rather than telling means demonstrating emotions or plot points through actions and reactions, not through telling your readers what happened or what a character felt. For example, instead of writing something like Yao was upset, which tells, give the character something to do to show the reader what’s going on: Yao clenched his fists and color rushed to his face shows the reader that Yao’s upset without having to tell them. Be wary of this in dialogue tags, too. Consider this sentence: ”Let’s go,” said Jenna impatiently.” It’s telling the reader that Jenna is impatient, but it’s not showing. Now consider this sentence: “Let’s go!” Jenna snapped, tapping her foot on the floor. Readers still understand that Jenna is feeling impatient, but you haven’t had to tell them; you’ve shown them.

Don’t believe any rule is set in stone. This can sound counterintuitive, especially after you’ve just been told several things to avoid doing in your fiction. However, part of writing is discovering your own voice and way of writing, and this means you should feel free to experiment. Just keep in mind that not all experiments work out, so don’t feel bad if you try something new and it doesn’t quite produce what you wanted. Judy Blume Judy Blume, Writer Writing requires creativity and individuality. "There are no hard and fast rules for writing, and no secret tricks, because what works for one person doesn’t always work for another. Everybody is different. That’s the key to the whole business of writing—your individuality."

Preparing to Write Your Fiction

Decide what format you want to write your fiction in. This may depend on what type of story you want to tell. For example, if you want to write an epic fantasy that spans multiple generations, a novel (or even a series of novels) may work better than a short story. If you're interested in exploring the psyche of a single character, a short story may be ideal.

Get an idea of some sort. All books start from a small idea, dream or inspiration that is slowly transformed into a larger and more detailed version of that same idea. The idea should be something you're interested in, something that’s really important to you; if you're not passionate about it, that will come through in your writing. If you're having issues coming up with good ideas, try these: Start with what you know. If you’re from a small town in rural Alabama, you may want to start off by thinking about stories you could tell about similar settings. If you want to write about something you don’t know, do your research. Trying to write a mythological story about Norse gods in modern settings could be fun, but if you don’t know anything about mythology, it’s not likely to be successful. Similarly, if you want to write a historical romance set in Regency England, you’ll probably have to do some research about social conventions and the like if you want your novel to appeal to readers. Make lists of random things: “the curtain,” “the cat,” “the investigator,” etc. Take each word and add a few things. Where is it? What is it? When is it? Make up a paragraph about it. Why is it where it is? When did it get there? How? What does it look like? Make up some characters. What is their age? When were they born, and where? Do they live in this world? What is the name of the city they are in now? What is their name, age, gender, height, weight, hair color, eye color, ethnic background? Try making a map. Draw a blob and make it an island, or draw lines indicating rivers. Who lives in this place? What would they need to do to survive in it?

Start keeping a writing journal. As a writer, it’s a good idea to write down ideas as they come to you. Jotting down your ideas can help you remember and build on them. Journals are amazing helpers when it comes to getting good ideas. Keep your journal with you all the time, since you never know when inspiration will strike! Your “journal” doesn’t have to be a diary or notebook. You can write notes in a memo app on your phone or even on sticky notes.

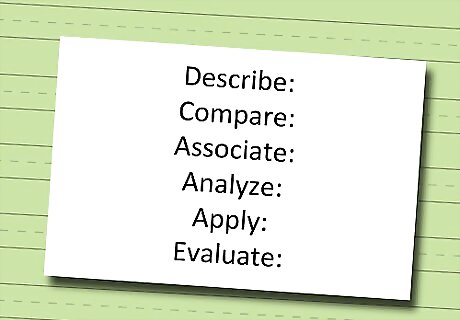

Brainstorm your topic using "Cubing." Cubing asks you to examine a topic from 6 separate angles (hence the name). For example, if you want to write a story about a wedding, consider the following angles: Describe: What is it? (A ceremony that results in the marriage of two people; a party or celebration; a ritual) Compare: What is it like or not like? (Like: other religious rituals, other types of parties; Not like: an average day) Associate: What else does it make you think of? (Expenses, dresses, church, flowers, relationships, arguments) Analyze: What parts or elements is it made up of? (Usually, a bride, a groom, a wedding dress, a cake, some guests, a venue, some vows, decorations; figuratively, stress, excitement, exhaustion, happiness) Apply: How is it used? How could it be used? (Used to unite two people in a legal contract of marriage) Evaluate: How can it be supported or opposed? (Supported: people who love each other get married to be happy together; Opposed: some people get married for bad reasons)

Make a mind map of your topic. You can create visual representations of how elements in your story relate by making a mind map, also sometimes known as a “cluster” or “spiderweb.” Start in the middle with your main character or conflict, and draw lines outward to other concepts. See what would happen if you connect these other elements in different ways. Mind maps are a useful way of organizing any type of information in a concise, visual way. They can help you visualize how different characters and other elements of your story are connected to one another and make it easier for you to remember key concepts. If you need help getting your mind map started, consider using software or an app such as Mindmeister, iMindMap, or SpiderScribe.

Ask “what if” questions about your story and characters. Say you have come up with a character: a young woman in her early 20s who lives in small-town Georgia. Ask yourself what would happen if this character was put into different situations. What would happen if she decided to take a job in Sydney, Australia, even though she’s never left the country? What would happen if she had to suddenly take over her family’s business, even if she’s always wanted to move away? Putting your characters in a variety of situations will help you decide what conflicts they may face and how they could handle them. This exercise can also help you determine what’s most important to your character(s) and whom they might (and might not) connect with.

Brainstorm your topic by researching. If you want to write about a particular type of setting or event, such as the medieval Wars of the Roses, do a little research. Find out who the major historical figures were, what actions they took, why they did what they did. George R.R. Martin’s famous Game of Thrones books were inspired by his fascination with the English medieval era, but he took his research and made his own world and characters out of it. EXPERT TIP Megaera Lorenz, PhD Megaera Lorenz, PhD wikiHow Staff Writer Megaera Lorenz is an Egyptologist and Writer with over 20 years of experience in public education. In 2017, she graduated with her PhD in Egyptology from The University of Chicago, where she served for several years as a content advisor and program facilitator for the Oriental Institute Museum’s Public Education office. She has also developed and taught Egyptology courses at The University of Chicago and Loyola University Chicago. Megaera Lorenz, PhD Megaera Lorenz, PhD wikiHow Staff Writer "When you're writing fiction, especially in research-heavy genres like historical, it can be easy to get hung up on minor details. If you can't find a piece of information quickly (like how much it cost to take a train from Chicago to Los Angeles in 1936), just leave a note for yourself and come back later to fill it in once you've done the research."

Use other sources for inspiration. Engaging with other types of creative work can provide you with a springboard for your own. Watch several movies or read several books in the same genre as your story to get an idea of how stories like those tend to progress. Make a soundtrack of music that sounds like something characters in your story would listen to, or how you imagine the soundtrack to the movie adaptation of your story would sound.

Feed your ideas with observations. A good writer is also a good reader and a good observer. Make observations about the world around you that you may want to incorporate into your fiction. Take notes on conversations you hear. Go to the library and read up on interesting topics. Go outside and look at nature. Let the idea mix with other ideas.

Writing Your Fiction

Figure out the basic setting and plot. You need to have a solid sense of what your story’s world is like, who lives in the world, and what will happen in your story before you start writing full scenes and chapters. If you have a good understanding of your characters, which you should have after brainstorming, let their personalities and flaws guide your plot. For setting, ask yourself questions like these: When is it? Is it in the present? The future? The past? More than one? What's the season? Is it cold, hot or mild? Is it stormy? Where is it? Is it in this world? A different world? An alternate universe? What country? City? Province/State? For plot, ask yourself questions like these: Who is in it? What is their role? Are they good or bad? What flaws do they have? What goals do they have? What is the precipitating incident that made this story happen in the first place? Is there something that happened in the past that could affect what happens in the future? Even if you start in the middle of the action, it’s important that you already have an idea of what happened beforehand. Even if you only imply or hint at the events that took place before the start of your story, it will be easier for you to be internally consistent and for your readers to fill in the blanks if there’s an established backstory.

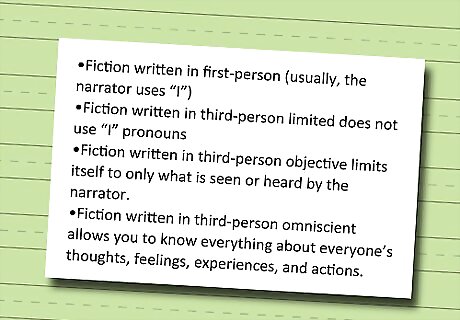

Decide what point of view (POV) you want your story to use. Point of view is very important in fiction, because it determines what information readers are given and how readers connect to the characters. Although point of view and narration are very complicated subjects, your basic choices are first person, third person limited, third person objective, and third person omniscient. Although it’s less common than the other choices, some writers also use second person. Whichever you choose, be consistent. Fiction written in first person (usually, the narrator uses “I”) can emotionally engage your reader because they will identify with the narrator. You can’t get into the heads of other characters as much, however, because you have to restrict the narration to what your central character could know or experience. Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre is an example of a novel written in first person. Fiction written in third person limited does not use “I” pronouns. The story is told from the POV of one character, relating only what they can see, know, and experience. It is a very common POV for fiction, because readers can usually still easily connect with the characters. Stories told this way can focus exclusively on the POV of one character (for example, the main character in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story “The Yellow Wallpaper”) or can shift between multiple characters (for example, the POV chapters devoted to different characters in the Game of Thrones books, or the alternating POV chapters between heroine and hero in most category romance novels). If you do shift between POV, be very clear when this has occurred by using a chapter or section break, or clear chapter labels. Fiction written in third-person objective limits itself to only what is seen or heard by the narrator. This type of POV is difficult to pull off, because you can’t go inside a character’s head and explain motivations or thoughts, so it can be difficult for readers to feel connected to the characters. However, it can be used effectively; for example, many of Ernest Hemingway’s short stories are written in third-person objective. Fiction written in third person omniscient allows you to know everything about everyone’s thoughts, feelings, experiences, and actions. The narrator can go into any character’s head and can even tell the reader things that no characters know, such as secrets or mysterious events. The narrators of Dan Brown’s books are usually third-person omniscient narrators. Second person narratives draw the reader into the story by putting them in the role of the narrator/POV character. They use “you” instead of “I” or “he/she/they.” For example: “It is November, but the early chill of winter is already creeping into your bones. You pull your scarf up over your nose to shield it from the frosty air.”

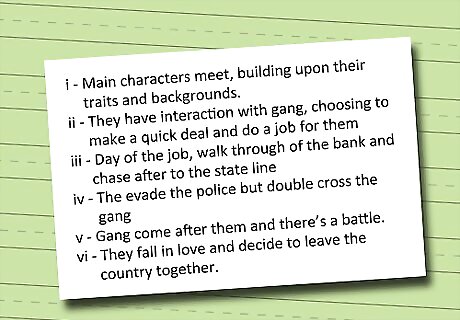

Outline your story. Use Roman numerals, and write a few sentences or paragraphs on what is going to happen in that chapter. You don’t have to have a hugely detailed outline if you don’t want to. In fact, you may find that as you write, your story deviates from the outline you had originally, and that’s natural. Sometimes writers just note what the emotional beat of a chapter should be (e.g., “Olivia is distraught and questions her decisions”), rather than trying to figure out what specific events happen.

Start writing. You may want to try pen and paper instead of the computer for the first draft. If you're sitting at a computer and there's one part that you just can't seem to get right, you could find yourself sitting there for ages trying to figure it out, typing and re-typing. With pen and paper, you just write it and it's on paper. If you get stuck, you can skip it and keep going. Just start wherever seems like a good place and write. Use your outline when you forget where you're going. Keep on going until you get to the end. If you're more of a computer person, a software program like Scrivener may help you get started. These programs let you write multiple little documents, such as character profiles and plot summaries, and keep them all in the same place.

Approach your writing in chunks. If you try to begin by thinking to yourself, “I’M GOING TO WRITE THE NEXT GREAT AMERICAN NOVEL,” you may be setting yourself up for failure before you even get started. Instead, take your writing 1 small goal at a time: a chapter, a few scenes, a character sketch.

Read dialogue aloud as you write it. One of the biggest problems that beginning writers often have is writing dialogue that sounds like no words that a living, breathing human has ever said. This is particularly a problem for writers of historical fiction and fantasy, where the temptation is to make the language sound elevated and elegant, sometimes at the expense of allowing readers to connect. Dialogue should flow naturally, even though it will probably be more compressed and meaningful than real-life speech. While in real everyday speech, people often repeat themselves and use filler words such as “um” and “uh,” use these sparingly on paper. They can end up distracting the reader if overused. Use your dialogue to forward the story or show something about a character. While people do have meaningless or shallow conversations all the time in real life, they’re not interesting to read on paper. Use the dialogue to convey the emotional state of a character, set a conflict or plot point in motion, or hint at what’s going on in a scene without stating it directly. Try not to use dialogue that is too on the nose. For example, if you’re writing about a couple’s unhappy marriage, your characters probably shouldn’t explicitly tell each other “I’m unhappy with our marriage.” Instead, show their anger and frustration through dialogue. For example, you could have one character ask the other what they want for breakfast and have that character respond with an answer that’s not related to the question in any way. This shows that the characters are having trouble listening to each other and communicating effectively without having to have one of them say “We’re not communicating effectively.”

Keep the action plausible. Your characters should drive the action of your story, and this means that you can’t have a character do something completely out of character simply because the plot requires it. Characters may do things that they wouldn’t normally do if the circumstances are extraordinary, or if it is part of their arc (for example, ending up in a different place than they began the story), but they should for the most part be consistent. For example, if your main character is terrified of flying because she survived a plane crash as a child, she wouldn’t casually take a flight to another state because the plot needs her to go there. Similarly, if your hero has had his heart broken by former loves and has become emotionally withdrawn, he can’t suddenly decide he’s in love with the heroine and pursue her without reservation. People don’t act that way in real life, and readers expect realism even in fantasy situations.

Take a break. After you have the first draft all on paper, take some time off from the story. This advice comes straight from famous author Ernest Hemingway, who said he always took nights off because “if you think consciously or worry about [your story] you will kill it and your brain will be tired before you start.” Go to the movies, read a book, ride a horse, go for a swim, dine out with some friends, go for a hike and get some exercise! When you take breaks, you're more inspired when you return to your fiction.

Re-read your work. This advice is also backed up by Hemingway, who insisted that you have to “read it all every day from the start, correcting as you go along, then go on from where you stopped the day before.” While you're reading it, use a red pen to make any notes or corrections you want. In fact, make lots of notes. Think of a better word? Want to switch some sentences? Does that dialogue sound too immature? Think that cat should really be a dog? Note those changes! Read your story aloud, because this helps you find mistakes.

Understand that first drafts are never perfect. If an author tells you that she wrote her entire beautifully plotted, gorgeously executed novel in one go without any trouble, she’s lying to you. Even masters of fiction writing, such as Charles Dickens and J.K. Rowling, write terrible first drafts. You may end up discarding huge chunks of prose or plot because they no longer work. That’s not only acceptable, it’s almost always essential to produce the refined product that your readers will crave.

Revising Your Fiction

Revise, revise, revise. Revision literally means to re-view something, to look at it again. Look at your fiction from the point of view of your readers, not you as a writer. If you had paid money to read this book, would you be satisfied? Do you feel a connection to your characters? Revision can be incredibly hard; there’s a reason why in the writing business it’s often talked about as “killing your darlings.” Don't be afraid to cut out words, paragraphs, and even entire sections. Most people pad their stories with extraneous words or passages. Cut, cut, cut. That is the key to success.

Experiment with different techniques. If something in your story isn’t working, change it up! If it's written in first person, put it in third person. See which you like better. Try new things, add new plot points, add different characters or put a different personality on a current character, etc.

Eliminate fluff. Particularly when you’re just starting out, you may try to use shortcuts to express something, such as overusing adverbs and adjectives to describe how an event or experience feels. Mark Twain offers some good advice on dealing with fluff words: “Substitute ‘damn’ every time you’re inclined to write ‘very.’ Your editor will delete it and the writing will be just as it should be.” For example, consider this sentence from Stephenie Meyer’s New Moon: “‘Hurry, Bella,’ Alice interrupted urgently.” Interrupting is itself an urgent action: it puts a stop to another action. The adverb doesn’t actually add anything to the action. In fact, this sentence doesn’t even need a dialogue tag; you can show one character interrupting another by using an em-dash, like this:“Sure,” I said, “I was just ab--”“Come on already!”

Slice out clichés. Writers often lean heavily on clichés, especially in early drafts, because they’re very familiar ways of expressing an idea or image. However, that’s also their weakness: everyone has read that a character “lives life to the fullest,” so it lacks genuine impact. Consider this advice from playwright Anton Chekhov: “Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass.” This advice also points out the usefulness of showing rather than telling.

Check for continuity errors. These are the little things that can get lost while you’re drafting but that readers notice immediately. Your character might have been wearing a blue dress at the beginning of the chapter but is now wearing a red dress in the same scene. Or one character leaves the room during a conversation but is back in the room a few lines later without having been shown re-entering it. These little errors can quickly irritate readers, so read carefully and correct them.

Read your fiction out loud. Sometimes, dialogue can look perfectly fine on the page but sound cringe-worthy when actually spoken by people. Or you may discover you’ve written a sentence that extends for an entire paragraph and even you get lost by the end. Reading your work aloud helps you catch awkward passages and places that have information gaps.

Submitting Your Fiction

Copy-edit your manuscript thoroughly. Go through every line, looking for typos, misspellings, grammatical errors, awkward words and expressions, and clichés. You can go through looking for a specific thing, like spelling errors, and then again for punctuation errors, or try to fix everything at once. When copy-editing your own work, you will often read what you thought you wrote rather than what you really wrote. If you can, ask someone else to help you copy-edit your manuscript. A friend who also reads or writes fiction could help you see errors that you didn’t catch on your own.

Find a journal, agent, or publisher to submit your work to. Most publishers don’t accept short stories, but many journals will accept short-story submissions. Many large publishers will not accept unsolicited manuscripts from writers without an agent, but some smaller publishers are happy to look at even first-time writers’ works. Look around and find a venue that matches your style, your genre, and your publishing goals. There are many manuals, websites, and organizations dedicated to helping writers find a venue for publication. Writers Market, Writer’s Digest, Book Market, and Writing World are good places to start. You can also choose to self-publish, an increasingly popular option for writers. Places such as Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, and Lulu all have guides on how to publish your book with them.

Format your work and put it into manuscript form. Follow any guidelines set by your publisher’s submission requirements first. Follow submission guidelines precisely, even if they conflict with information found here. If they ask for 1.37” margins, make your margins 1.37”. (Standard margins are either 1” or 1.25”, though.) Submissions that don’t follow guidelines are rarely read or accepted. In general, there are some rules to follow when formatting a manuscript for submission. Create a cover page with the manuscript title, your name, contact information, and word count. This should be centered horizontally and vertically, with a space between each line. Alternatively, place your personal information -- name, phone number, email address -- in the upper left-hand corner of the first page. In the right-hand corner, put the word count rounded to the nearest 10. Press enter a few times and then put your title. The title should be centered, and may be put in all caps. Start the manuscript on a new page. Use a clear, legible serif font such as Times New Roman or Courier New set to 12pt. Double space all text. Left-justify your text. For section breaks, center 3 asterisks (***) on a new line, then hit the “enter” key and begin the new section. Start all new chapters on a new page, with the title centered. On every page except the first, include a header that has the page number, a shortened version of the title, and your last name. For print submissions, print the manuscript on high quality 8½" x 11" (or A4) 20lb bond paper.

Submit your manuscript. Follow all the submission guidelines to the letter. Then, sit back and wait for a response! When you’re submitting your story for publication, it’s very likely that you’ll get a few (or more than a few) rejections before someone accepts your work. This is totally normal—don’t let it discourage you! Just because one publisher rejects your work doesn’t mean that another will. Sometimes a publisher will reject a story not because it’s bad, but because it’s just not what they’re looking for in terms of style and content.

Comments

0 comment