views

X

Research source

[2]

X

Research source

This may seem like an overwhelming amount of work, but by adhering to a few guidelines and putting in the necessary effort, you'll soon have a report your instructor will love.

Formulating a Plan for Your Report

Get a head start on your lab report as soon as possible. You may have difficulty fighting the urge to procrastinate, but keep in mind that feedback and revisions can sometimes take up to a week. If you wait, you may forget a lot of important details from the experiment. Having a rough version of your report at the ready a month in advance can save you from unnecessary stress and from having to turn in unpolished work. You may have performed supplemental experiments/simulations or repeated your initial experience after receiving your first round of feedback. Feedback should go through the following stages ideally: (a) Self-review and revision (b) Peer review and constructive feedback (c) Advisor/instructor review and feedback

Write your report with the primary goal of readability. The goal of your experiment or the goal of proving or disproving certain hypotheses is essentially unimportant when you are writing a lab report. The data contained in it could be anything, and you may very well have to write lab reports in the future that seem silly or unnecessary. The goal of your lab report is to be read and evaluated by another person, like your instructor. It can help remind yourself of this goal at the beginning of every section before starting writing. When you finish a section of your report, read it through carefully, and at the end of it, ask yourself: was that easy to read and understand? Did I succeed in my goal?

Determine your present audience and potential future ones. The narrowest purpose of your lab report is to enable your seniors, advisors, and/or an evaluation committee to confirm your ability to consistently and clearly produce a report. But once you start devising and performing labs of your own, your peers or juniors may utilize it as a resource. If you believe your paper might be of use to researchers in another discipline, like social science, you may want to include definitions or explanations for the more technical jargon used in your paper.

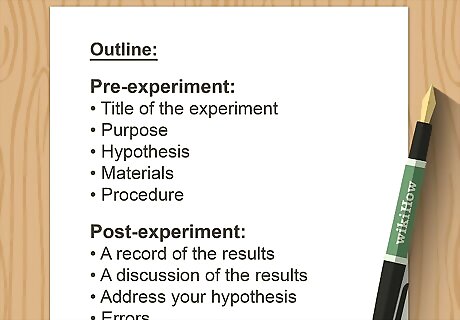

Outline the general structure of your lab report. Take a piece of scrap paper and pencil and list the necessary sections of your lab report in order. Under each section, jot a few sentences that summarize what must be covered in that section. Since different instructors have different preferences, you should check your lab report handout or course syllabus to verify expectations for the order and content of your report. Most lab reports are organized, first to last: background information, problem, hypothesis, materials, procedure, data, and your interpretation of what happened as a conclusion.

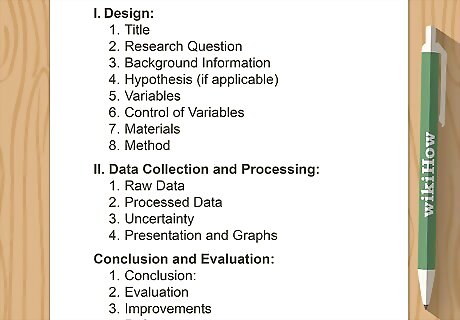

Break sections of your report into subsections, if necessary. Technical aspects of your paper might require significant explanation. This may necessitate the use of subsections so that you can appropriately delve into and explain those nuanced aspects of your lab problem. The organization of the body of your lab report will be specific to your problem/experiment. You may also have a separate section for the statement of your design methodology, experimental methodology, or proving subsidiary/intermediary theorems in your report.

Writing a Top-down Outline

Familiarize yourself with the top-down approach. The idea behind this style is that you should begin with the most important elements (the "head" points) and refine each of those all the way to the basic level. This can be divided into roughly three stages: The section-level outline The subsection-level outline The paragraph-level outline

Write your initial outline in a top-down style. This will give you a better idea of how to get from a blank page to a finished report. Begin with each of your section headings, leaving plenty of space between headings for subsection and paragraph-level information. Avoid being too wordy at this stage, the goal of your outline is to capture the flow and form of your report. Bullet points are invaluable when you reach the paragraph level of your report. These will allow you to note important terms, phrases, and data that will need to be integrated with the text of your report. Take special note, at the paragraph level, of important symbols, protocols, algorithms, and jargon.

Remember figures, tables, and graphs at the paragraph-level. You will need to weave these into the text of your report in a way that is logical and intuitive. Use a unique bullet to indicate where an image must be integrated into your report. You might also consider using simple figures as a way of cutting down unnecessary wordiness.

Use organizational tools, like highlighters and sticky notes. Highlighters can help you color code and coordinate sections of your outline with supplemental papers, like research, print-outs, and hand-outs. A colorful sticky note, on the other hand, can alert you to something you've forgotten or have yet to do, like making a graph from your data.

Writing Your Introduction and Abstract

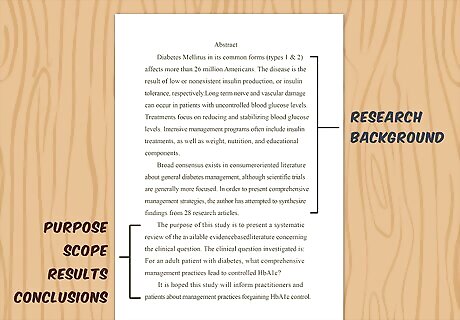

Craft your title and abstract carefully. These two items are the most visible parts of your lab report, and will therefore receive the most attention. A bland title or incomprehensible abstract can limit the impact your report has on your peers. The title of your report should reflect what you have done and bring out any eye-catching factor of your work. The abstract should be concise, generally about 2 paragraphs or about 200 words in length.

Refine your abstract down to crucial information. Your abstract should contain the essence of your report. This can generally be conveyed by the following points, in varying amounts of detail, as is appropriate for your case: (a) Main motivation (b) Main design point (c) Essential differences from previous work (d) Methodology (e) Noteworthy results, if any

Devise your introduction. Nearly all reports should start with an introduction section. After the title and abstract, it is generally accepted that the introduction and conclusion are the second most widely read part of any given report. This section should answer the following questions: What is the setting of the problem? This is, in other words, the background. In some cases, this may be implicit, and in some cases, this question may be merged with your paper's motivation. What is the problem you are trying to solve? This is also known as the problem statement of your report. Why is your problem important? This is the motivation behind your report. In some cases, it may be implicit in the background, or even the problem statement. Is the problem still unsolved? The constitutes the statement of past/related work, and should be conveyed succinctly.

Model your intro off your top-down outline. Since the introduction of your report is little more than a summary of your lab in words, your outline can be an excellent guide for your writing here. In many cases, the rest of your report will have the same, or a similar, flow. Each section of the body of your report can be thought of as an in-depth look at the points mentioned in the introduction.

Include substantiation and critical details in your intro. The intricacies of the lab experiment you are writing about in your report may not be clear to every reader. To prevent confusion and create a strong logical chain throughout your report, you should, if applicable to your situation, also consider answering the questions: Why is your problem difficult to solve? How have you solved the problem? What are the conditions under which your solution is applicable? What are the main results? What is the summary of your contributions? This, in some cases, maybe implicit in the body of your introduction. Sometimes it helps to state contributions explicitly. How is the rest of your report organized?

Provide a background section, if necessary. If vital background information needs to be expressed to your readers early in the paper, this information can be expanded into its own sub-section. It is common to state that "the reader who knows this background can skip this section" at the beginning of this section.

Writing the Body of Your Lab Report

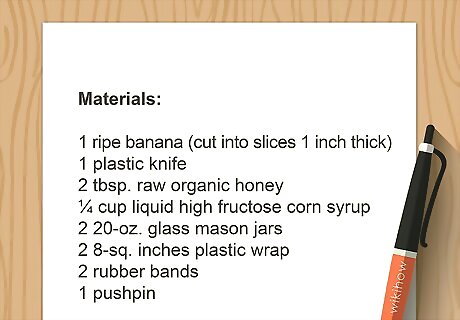

Write your section on materials and methods. The key to writing this section is not overwhelming your readers with too much information. If you need to describe or explain specialty equipment or theory that is used, you should: Describe the equipment or theory in a short paragraph. Consider including a diagram of the apparatus for equipment. Theoretical elements should be included in both natural and derived forms. Include what strategies and methodologies you are using for the experiment.

Consider a section interpreting related work. If there have been similar experiments performed, or if you are expanding upon or applying a new approach to past research, interpreting how that research-informed and directed your own will naturally highlight differences between your experiment and others. One possible placement is toward the beginning of the report, after your intro and background sections. Another idea is to place it at the end of the report, just before your conclusion. This is a matter of preference, and depends on the preferences of your instructor or, potentially, the following aspects: A large quantity of work closely related to your work would likely be best closer to the beginning of your report. This will allow you to point out differences best. Relevant work that is substantially different from your own is probably best toward the end of your report. However, this placement risks leaving your readers wondering about differences until the end of your report.

Differentiate your report from past and/or related work, if necessary. It is common to have this as a separate section where you explain what makes your experiment novel. Here, you must try to think of dimensions of comparison concerning other work. For instance, you may compare your lab in terms of: Functionality Performance Approach Note: each of these comparisons can be further distinguished by: 1. Functionality 2. Metric 3. Implementation 4. Anticipated results or successes

Use a table or graph to clearly indicate differences. Although this may not be necessary in your particular case, many lab reports use graphics to juxtapose differences between your work and that of others. This helps to illustrate the differences between the two at a glance for your readers. Make sure to cite the work of others so you can avoid plagiarism and give yourself more credibility. If you decide to use a chart, it is a general convention that you include your own work in either the first or last column.

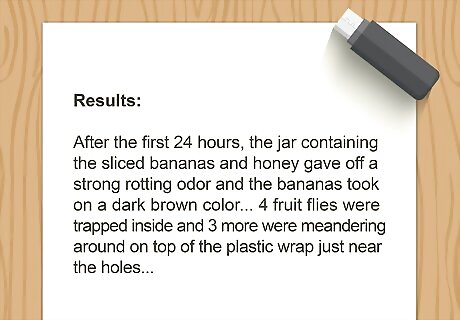

State your results in your data section. The results section of your report will change according to the kind of lab you have performed, its goals, implementation, and so on. This section will need to lay out all data from your experiment without making subjective comments or discussing opinions. Figures and tables should be used to organize your data as clearly and succinctly as possible. All figures and tables should be titled descriptively, numbered sequentially, and include a descriptive legend for symbols, abbreviations, etc. The columns and rows of all tables and the axes of graphs should be labeled.

Summarize your main points for data-heavy results sections. If your lab has yielded abundant results, the important points in that data can be missed. Your readers will stand a better chance of remembering these if you include a summary of the indispensable information in a separate sub-section at the end of your results section.

Define your data and its purpose impartially and clearly. Even if your data has confirmed your hypothesis beyond your wildest expectations, the results section of your report should be objective. To ensure that your data and its purpose are both clear to your readers, you might ask the following questions: What aspects of your system or algorithm are you trying to evaluate? Why? What are the cases of comparison? If you have proposed an algorithm or a design, what do you compare it with? What are the performance metrics? Why? What are the parameters understudy? What is the experimental setup?

Concluding Your Lab Report

Interpret your data and results in the discussion section. This will require you to logically connect your results to existing theory and knowledge. Any improvements to technique or equipment that you may have realized over the course of your lab should also be included here. Predictions are expected in this section, though these should be clearly identified as such. Future experiments that might clarify your results should be suggested.

Address any other weaknesses in your discussion section. Even if your natural inclination is to gloss over weak points in your lab report, this can be harmful to your credibility. If you state these explicitly, you can create trust and professional respect between you and your reader.

Add a separate conclusion section for longer reports. For labs that are data-heavy or incorporate highly complex principles, you might need to use your discussion section to speak on those results independently. Your conclusion should look at your results about the entire experiment.

Make your conclusion count. It is generally accepted in academic communities that readers focus most attention on the title, abstract, introduction, and conclusion of a lab or academic paper. In that sense, this section is quite important. Precisely and in as few words as possible state the main findings of your lab. Answer the question: How has the reader become smarter, or how does your research and work fit into the bigger picture?

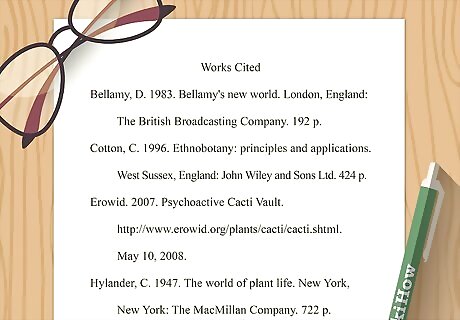

List all sources used in your lab report. This is the final section of your lab report and is separate from your bibliography. Your section on the literature cited should only include references that appear in your written report. You should alphabetize this list by author's last name, and then format the remaining information according to the source requirements.

Getting the Most Out of Peer Review

Respect the process. Though it might seem tiresome to you, having to slog through the report of another at the direction of your instructor, offering feedback and comments, is an important part of the process. It is so important, in fact, that academic papers are rarely accepted until thoroughly peer-reviewed. Many academic papers are reviewed 3 times by 3 sets of reviewers before they are published. Take constructive criticism for your lab report if you plan to pursue a career in academics.

Seek review from peers involved in different projects. This is especially important if you are working with a group in a lab. Each member of the group, being a part of the lab, will likely be unable to critique the report objectively. You might also make use of your campus writing center, if available. Here you can have a fresh set of eyes assess the quality of your report.

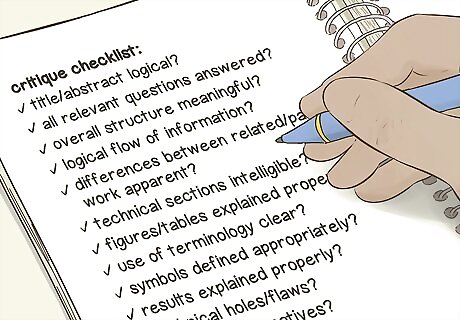

Write a critique checklist. Though not necessary, you can help your reviewer do the best job possible by providing him with a checklist of key points. For example, if you tend to use too much jargon, you might include, "clear jargon" in your critique checklist. Other items you might want to highlight for your reviewer: Title/abstract logical, understandable, and eye-catching? All relevant questions answered in the introduction? Overall structure of sections and subsections meaningful? Is there a logical flow of information? Differences between related/past work apparent? Technical sections intelligible? Figures/tables explained properly? Use of terminology clear? Symbols defined appropriately? Results explained properly? Technical holes/flaws? Potential problems or alternatives?

Accept feedback from your peers politely. In some cases, you might have a difference of opinion from your reviewer. In other cases, your reviewer might give weak, questionable, or incorrect feedback. In still other cases, a reviewer can save you from making a critical error! Remember that your reviewer is taking time out of his day to read your report, and express your gratitude for his feedback.

Critique structure, clarity, and logic, not the writer. It can be easy to get carried away when making a critique. Reviewers may even get frustrated with the state of a report, which can lead to personal comments. This can be offensive, and defeats the purpose of the peer review process, which is to improve the report, not make enemies. Try to keep your comments as impersonal as possible. Locate specific elements that can be isolated, targeted, and improved. While taking feedback from a peer, take the comments on their technical merit and avoid being defensive.

Comments

0 comment