views

X

Research source

Music notation is the representation of sound with symbols, from basic notations for pitch, duration, and timing, to more advanced descriptions of expression, timbre, and even special effects. This article will introduce you to the basics of reading music, show you some more advanced methods, and suggest some ways to gain more knowledge about the subject.

Learning the Basics

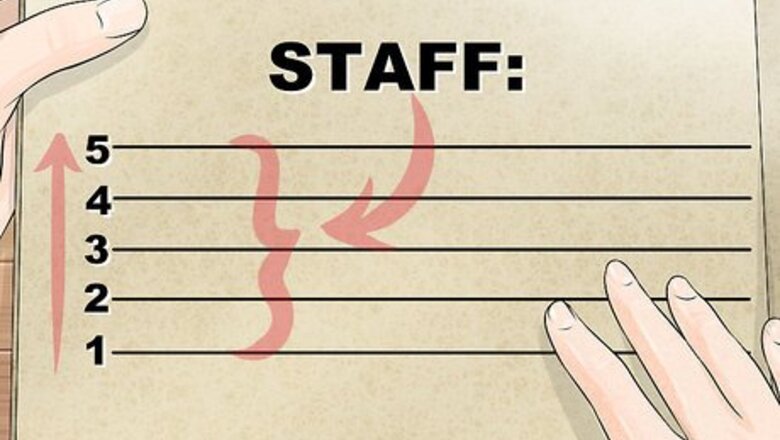

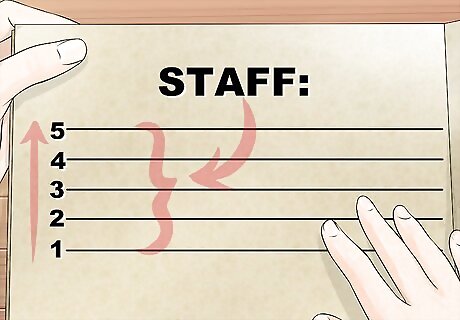

Get a handle on the staff. Before you are ready to start learning music, you must get a sense for the basic information that virtually everyone who reads music needs to know. The horizontal lines on a piece of music make up the staff. This is the most basic of all musical symbols and the foundation for everything that is to follow. The staff is an arrangement of five parallel lines, and the spaces between them. Both lines and spaces are numbered for reference purposes, and are always counted from lowest (bottom of the staff) to highest (top of the staff).

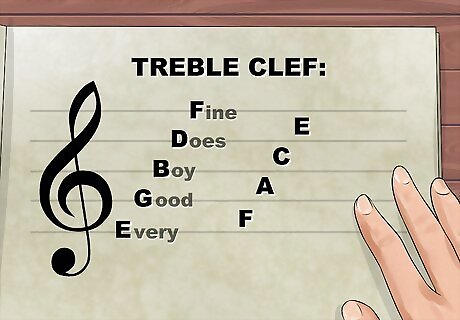

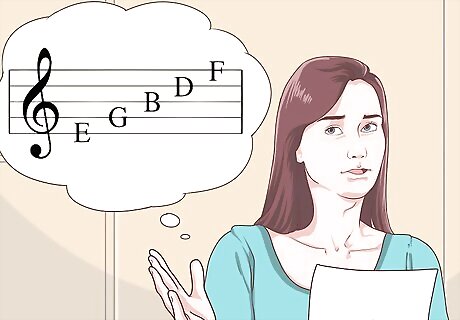

Start with the treble clef. One of the first things you'll encounter when reading music is the clef. This sign, which looks like a big, fancy cursive symbol at the left end of the staff, is the legend that tells you approximately what range your instrument will play in. All instruments and voices in the higher ranges use the treble clef, and for this intro to reading music, we'll focus primarily on this clef for our examples. The treble clef, or G clef, is derived from an ornamental Latin letter G. One good way to remember this is that the line at the center of the clef's "swirl" wraps around the line that represents the note G. When notes are added to the staff in the treble clef, they will have the following values: The five lines, from the bottom up, represent the following notes: E G B D F. The four spaces, from the bottom up, represent these notes: F A C E. This may seem like a lot to remember, but you can use mnemonics—or word cues—that may help you remember them. For the lines, "Every Good Boy Does Fine" is one popular mnemonic, and the spaces spell out the word "FACE." Practicing with an online note recognition tool is another great way to reinforce these associations.

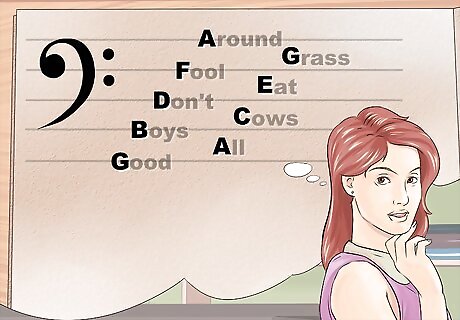

Understand the bass clef. The bass clef, also known as the F clef, is used for instruments in the lower registers, including the left hand of the piano, bass guitar, trombone, and so on. The name "F clef" derives from its origins as the Gothic letter F. The two dots on the clef lie above and below the "F" line on the staff. The staff of the bass clef represents different notes than that of the treble clef. The five lines, bottom to top, represent these notes: G B D F A ("Good Boys Don't Fool Around"). The four spaces, bottom to top, represent these notes: A C E G ("All Cows Eat Grass").

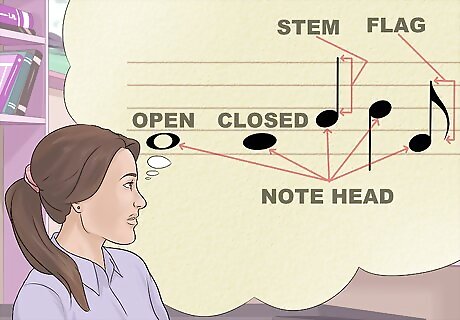

Learn the parts of a note. Individual note symbols are a combination of up to three basic elements: the note head, the stem, and flags. The note head. This is an oval shape that is either open (white) or closed (black). At its most basic, it tells a performer the pitch and duration of a given note. The stem. This is the thin vertical line that is attached to the note head. When the stem is pointing up, it joins on the right side of the note head. When the stem is pointing down, it joins the note head on the left. The direction of the stem has no effect on the note, but it makes notation easier to read and less cluttered. The general rule on stem direction is that at or above the center line (B for treble clef or D for bass clef) of the staff, the stem points down, and when the note is below the middle of the staff, the stem points up. The flag. This is the curved stroke that is attached to the end of the stem. No matter if the stem is joined to the right or left of the note head, the flag is always drawn to the right of the stem, and never to the left! Taken together, the note, stem, and flag or flags show the musician the time value for any given note, as measured in beats or fractions of beats. When you listen to music, and you're tapping your foot in time to the music, you're recognizing that beat.

Reading Meter and Time

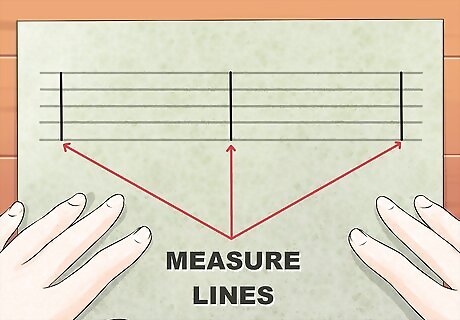

Learn about measure lines. On a piece of sheet music, you will see thin vertical lines crossing the staff at fairly regular intervals. These lines represent measures (called "bars" in some places); the space before the first line is the first measure, the space between the first and second lines is the second measure, and so on. Measure lines don't affect how the music sounds, but they help the performer keep their place in the music. As we'll see below, another handy thing about measures is that each one gets the same number of beats. For example, if you find yourself tapping "1-2-3-4" along to a piece of music on the radio, you've probably subconsciously found the measure lines already.

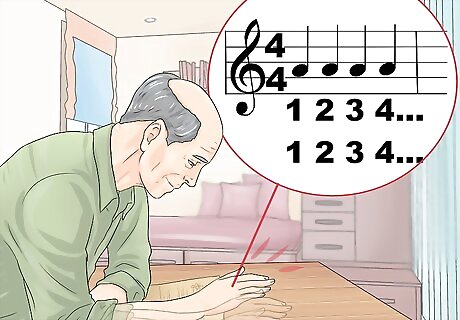

Learn about timing, or meter. Meter can be generally thought of as the "pulse" or the beat of music. You feel it instinctively when you listen to dance or pop music; the "boom, tiss, boom, tiss" of a stereotypical dance track is a simple example of meter. On a piece of sheet music, the beat is expressed by something that looks like a fraction written next to the first clef symbol. Like any fraction, there is a numerator, and a denominator. The numerator, written in the top two spaces of the staff, tells you how many beats there are in one measure. The denominator tells you the note value that receives one beat (the "pulse" that you tap your toe to). Perhaps the easiest meter to understand is 4/4 time, or "common" time. In 4/4 time, there are four beats in each measure and each quarter note is equal to one beat. This is the time signature you'll hear in most popular music. You can count along to common time music by counting "ONE two three four ONE two three four..." to the beat. By changing the numerator, we change the number of beats in a measure. Another very common time signature is 3/4. For example, most waltzes will have a steady "ONE two three ONE two three" beat, making them in 3/4 time. Some meters will be shown with a letter C instead of two numbers. 4/4 time is often shown as a big C, which stands for common time. Likewise, 2/2 meter is often shown as a big C with a vertical line through it. The C with the line through it stands for cut time (sometimes referred to as half common time).

Learning Rhythm

Get in the groove. Since it incorporates meter and time, "rhythm" is a crucial part of how the music feels. However, whereas meter simply tells you how many beats, rhythm is how those beats are used. Try this: tap your finger on your desk, and count 1-2-3-4 1-2-3-4, steadily. Not very interesting, is it? Now try this: on beats 1 and 3, tap louder, and on beats 2 and 4, tap softer. That's got a different feel to it! Now try the reverse: tapping loud on 2 and 4, and soft on beats 1 and 3. Check out Regina Spektor's Don't Leave Me. You can clearly hear the rhythm: the quieter bass note happens on beat 1 and beat 3, and a loud clap and snare drum happen on beats 2 and 4. You'll start to get a sense of how music is organized. That's what we call rhythm!

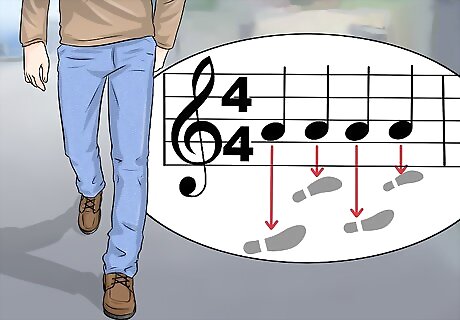

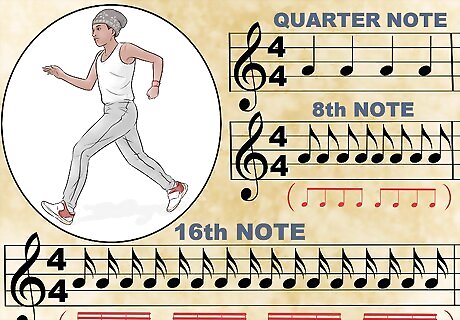

Imagine yourself walking. Each footstep will equal one beat. Those are represented musically by quarter notes because in much of Western music (meaning music of the western world, not just the music of Hank Williams!), there are four of these beats for every measure. Musically, the rhythm of your walking will look like this: Each step is one-quarter note. On a sheet of music, quarter notes are the solid black dots attached to stems without any flags. You can count that off as you walk: "1, 2, 3, 4-1, 2, 3, tw Quarter notes are referred to as "crotchets" in some places, such as the UK. If you were to slow your pace down to half that speed, so that you only took a step every two beats on the 1 and on the 3, that would be notated with half notes (for half a measure). On a sheet of music, half notes look like quarter notes, only they aren't solid black; they are outlined in black with white centers. In some places, half notes are called "minims". If you slowed your pace down even further, so that you only took a step every four beats, on the one, you would write that as a whole note—or one note per measure. On a sheet of music, whole notes look like "O"s or donuts; similar to half notes without stems.

Pick up the pace! Enough of this slowing down. As you noticed, as we slowed the notes down, we started taking away bits of the note. First, we took away the solid note, then we took away the stem. Now let's look at speeding things up. To do that, we're going to add things to the note. Go back to our walking tempo, and picture that in your mind (tapping your foot to the beat can help). Now imagine that your bus has just pulled up to the stop, and you're about a block away. What do you do? You run! And as you run, you try to flag the bus driver. To make notes faster in music, we add a flag. Each flag cuts the time value of the note in half. For example, an eighth note (which gets one flag) is 1/2 the value of a quarter note; and a 16th note (which gets two flags) is 1/2 the value of an eighth note. In terms of walking, we go from a walk (quarter note or quaver) to a run (eighth note or semiquaver)—twice as fast as a walk, to a sprint (sixteenth note or demisemiquaver)—twice as fast as a run. Thinking in terms of each quarter note being a step as you walk, tap along with the example above.

Beam up! As you can see with that above example, things can start to get a little confusing when there are a bunch of notes on the page like that. Your eyes start to cross, and you lose track of where you were. To group notes into smaller packages that make sense visually, we use beaming. Beaming merely replaces individual note flags with thick lines drawn between note stems. These are grouped logically, and while more complex music requires more complex beaming rules, for our purposes, we'll generally beam in groups of quarter notes. Compare the example below with the example above. Try tapping out the rhythm again, and see how much clearer beaming makes the notation.

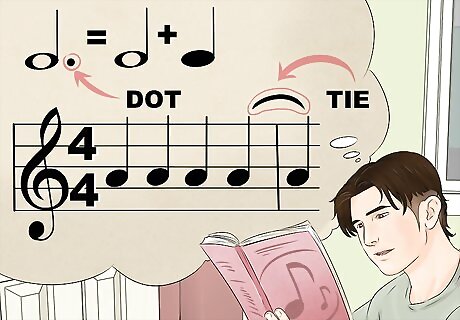

Learn the value of ties and dots. Where a flag will cut the value of a note in half, the dot has a similar—but the opposite—function. With limited exceptions that do not come into play here, the dot is always placed to the right of the note head. When you see a dotted note, that note is increased by one half the length of its original value. For example, a dot placed after a half note (minim) will be equal to the half note plus a quarter note. A dot placed after a quarter note (crotchet) will be equal to a quarter note plus an eighth note. Ties are similar to dots—they extend the value of the original note. A tie is simply two notes linked together with a curved line between the note heads. Unlike dots, which are abstract and based wholly on the value of the original note, ties are explicit: the note is increased in length by exactly as long as the second note value. One reason you would use a tie versus a dot is, for example, when a note's duration would not fit musically into the space of a measure (bar). In that case, you simply add the leftover duration into the next measure as a note, and tie the two together. Note that the tie is drawn from note head to notehead in the opposite direction as the stem.

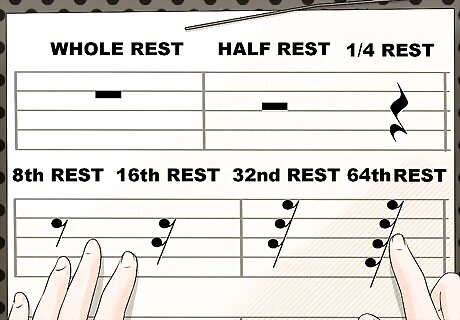

Take a rest. Some say music is just a series of notes, and they're half correct. Music is a series of notes and the spaces between them. Those spaces are called rests, and even in silence, they can really add motion and life to music. Let's take a look at how they're notated. Like notes, they have specific symbols for specific durations. A whole note rest is a rectangle descending from the 4th line, and a half note rest is a rectangle resting on the 3rd line and pointing upwards. The quarter note rest is a squiggly line, and the rest of the rests are an angled bar that looks like a number "7" with the same number of flags as their equivalent note value. These flags always sweep to the left.

Learning Melody

Make sure you understand the above, and then let's dive into the fun stuff: reading music! We now have the basics down: the staff, the parts of a note, and the basics of notating durations of notes and rests.

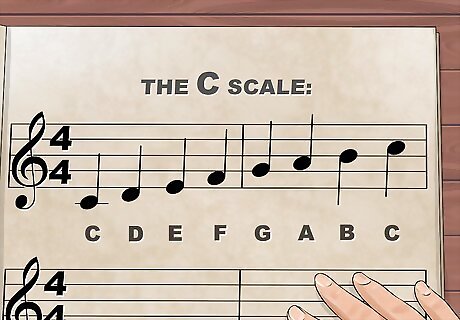

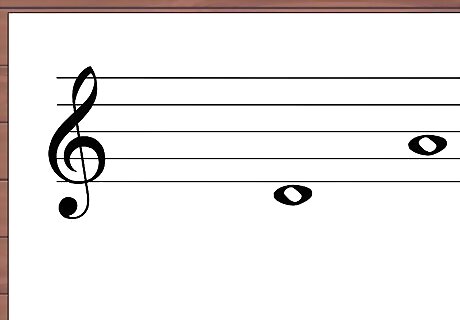

Learn the C scale. The C major scale is the first scale we use when teaching how to read music because it's the one that uses just natural notes (the white keys on a piano). Once you have that locked into your brain cells, the rest will follow naturally. First, we'll show you what it looks like, then we'll show you how to make sense of it, and begin to read music! Here's what it looks like on the staff. See the "C scale" above. If you'll take a look at the first note, the low C, you'll see that it actually goes below the staff lines. When that happens, we simply add a staff line for that note only—thus, the little line through the note head. The lower the note, the more staff lines we add. But we don't need to worry about that now. The C scale is made up of eight notes. These are the equivalent of the white keys on the piano. You may or may not have a piano handy, but at this point, it's important for you to begin to get an idea of not just what music looks like, but of what it sounds like, too.

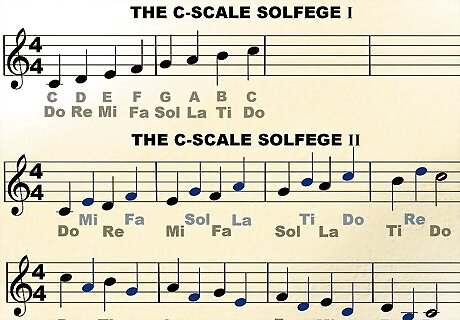

Learn a little sight singing—or "solfège." That may sound intimidating, but chances are, you already know it: it's the fancy way of saying "do, re, mi." By learning to sing the notes that you see, you'll begin to develop the skill of sight-reading—a skill that can take a lifetime to perfect, but will be useful right from the beginning. Let's take a look at that C scale again, with the solfege scale added. See the "C Scale Solfege 11" above. Chances are, you know the Rogers and Hammerstein song "Do-Re-Mi" from The Sound of Music. If you can sing the "do re mi" scale, do that now while you look at the notes. If you need a refresher course, you can hear the song on YouTube. Here's a slightly more advanced version, walking up and down the C scale using the solfège notes. See the "C Scale Solfege 1" above. Practice singing Solfege—part II a few times, until it becomes familiar. The first couple times, read very slowly so that you can look at each note as you sing it. The next couple times, substitute the "do re mi" for C, D, E. The goal is to sing the actual notes. Remember our note values from before: the high C at the end of the first line, and the low C at the end of the second line are half notes, while the rest of the notes are quarter notes. If you imagine yourself walking, again, there is a note for each step. The half notes take two steps.

Congratulations, you're now reading music!

Reading Sharps, Flats, Naturals, and Keys

Take the next step. So far we've covered the very basics of rhythm and melody, and you should possess the basic skills necessary that you now understand what all those dots and squiggles represent. While this might get you through basic Flutophone class, there are still a few more things you'll want to know. Chief among these are key signatures. You may have seen sharps and flats in music: sharp looks like a hashtag (♯) and a flat looks like a lowercase B (♭). They are placed to the left of a note head and indicate that the note to follow is played a half-step (semitone) higher for a sharp, or a half-step lower for a flat. The C scale, as we learned, comprises the white keys on the piano. When you're beginning to read music, it's easiest to think of the sharps and flats as the black keys. However, one should also note that sharps and flats are on white keys in some situations (for example, when the key signature calls for it). For instance, B sharp is played on the same note as C.

Know the whole tones and semitones. In Western music, notes are either a whole tone or a semitone apart. If you look at the C note on the piano keyboard, you'll see there's a black key between it and the next note up, the D. The musical distance between the C and the D is called a whole tone. The distance between the C and the black key is called a semitone. Now, you may be wondering what that black key is called. The answer is, “it depends.” A good rule of thumb is if you are going up the scale, that note is the sharp version of the beginning note. When moving down the scale, that note would be the flat version of the beginning note. Thus, if you are moving from C to D with the black key, it would be written using a sharp (♯). In this case, the black note is written as C♯. When moving down the scale, from D to C, and using the black note as a passing tone between them, the black key would be written using a flat (♭). Conventions like that make music a little easier to read. If you were to write those three notes going up and used a D♭ instead of a C♯, the notation would be written using a natural sign (♮). Notice that there's a new sign—the natural. Whenever you see a natural sign (♮) that means that the note cancels any sharps or flats previously written. In this example, the second and third notes are both "D"s: the first a D♭, and so the second D, since it goes up a semitone from the first D, has to have the note "corrected" to show the right note. The more sharps and flats scattered around a sheet of music, the more a musician must take in before the score can be played. Often, composers that previously used accidentals in previous measures may put "unnecessary" natural signs to provide clarity for the player. For example, if a previous measure in a D major piece used an A♯, the next measure that uses an A may be notated with an A-natural instead.

Understand key signatures. So far, we've been looking at the C major scale: eight notes, all the white keys, starting on C. However, you can start a scale on any note. If you just play all the white keys, though, you will not be playing a major scale, but something called a "modal scale," which is beyond the scope of this article. The starting note, or tonic, is also the name of the key. You may have heard somebody say "It's in the key of C" or something similar. This example means that the basic scale starts on C, and includes the notes C D E F G A B C. The notes in a major scale have a very specific relationship to each other. Take a look at the keyboard above. Note that between most notes, there is a whole step. But there is only a half step (semitone) between E and F, and between B and C. Every major scale has this same relationship: whole-whole-half-whole-whole-whole-half. If you start your scale on G, for example, it would be written as G-A-B-C-D-E-F#-G. Notice that in order to maintain the proper relationship between the notes of the scales, the F has to be raised a semitone so that it's a half step from the G, not a whole step. That's easy enough to read by itself, but what if you started a major scale in C♯? Now it starts to get complicated! In order to cut down the confusion and make music easier to read, key signatures were created. Each major scale has a particular set of sharps or flats, and those are shown at the very beginning of the music. Look again at the key of G. Instead of putting that sharp next to the F on the staff, we move it all the way to the left, and it is just assumed from that point on that every F you see is played as a F#.

Reading Dynamics and Expression

Get loud—or get soft! When you listen to music, you have probably noticed that it's not all at the same volume, all the time. Some parts get really loud, and some parts get really soft. These variations are known as "dynamics." If the rhythm and meter are the heart of the music, and notes and keys are the brains, then dynamics are surely the voice of the music. Consider the first version above. On your table, tap out: 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and 5 and 6 and 7 and 8, etc. (the and is how musicians "say" eighth notes). Make sure every beat is tapped at the same loudness, so that it sounds a bit like a helicopter. Now take a look at the second version. Notice the accent mark (>) above every F note. Tap that out, only this time, accent every beat that you see the accent mark. Now, instead of a helicopter, it should sound more like a train. With just a subtle shift in accent, we completely change the character of the music!

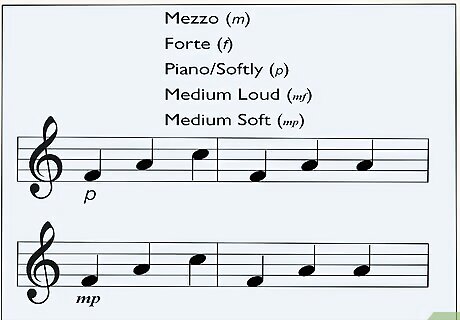

Play it piano, or fortissimo, or somewhere in between. Just like you don't always talk at the same level—you modulate your voice louder or softer, depending on the situation—music modulates in level too. The way the composer tells the musician what is intended is by using dynamic markings. There are dozens of dynamic markings you may see on a piece of music, but some of the most common ones you'll find will be the letters f, m, and p. p means "piano," or "softly." f means "forte," or "loud." m means "mezzo," or "medium." This modifies the dynamic after it, as in mf which means "medium loud", or mp, which means "medium soft." The more ps or fs you have, the softer or louder the music is to be played. Try singing the example above (using solfège—the first note in this example is the tonic, or "do"), and use the dynamic markings to notice the difference.

Get louder and louder and louder, or quieter and quieter and quieter. Another very common dynamic notation is the crescendo, and it's corollary, the decrescendo or "diminuendo". They are visual representations of a gradual change in volume which look like stretched-out "<" and ">" symbols. A crescendo gradually gets louder, and a decrescendo gradually decreases the volume. You'll notice that, with these two symbols, the "open" end of the symbol represents the louder dynamic and the closed end represents the quieter dynamic. For example, if the music directs you to gradually go from forte to piano, you'll see an f', then a stretched out ">", then a 'p'. Sometimes a crescendo or diminuendo will be represented as the shortened words cresc." (crescendo) or dim. (diminuendo).

Advancing

Keep learning! Learning to read music is like learning the alphabet. The basics take a little bit to learn, but are fairly easy, overall. However, there are so many nuances, concepts, and skills that you can learn that it can keep you learning for a lifetime. Some composers even go so far as to write music on staff lines that form spirals or patterns, or the even use no staff lines at all! This article should give you a good foundation to keep growing!

Learn these key signatures. There is at least one for every note in the scale—and the savvy student will see that in some cases, there are two keys for the same note. For example, the key of G♯ sounds exactly the same as the key of A♭! When playing the piano—and for the purposes of this article, the difference is academic. However, there are some composers—especially those that write for strings—who will suggest that the A♭ is played a little "flatter" than the G♯. Here are the key signatures for the major scales: Keys not using sharps or flats: C Keys using sharps: G, D, A, E, B, F♯, C♯ Keys using flats: F, B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭ As you can see above, as you move through the sharp key signatures, you add sharps one at a time until every note is played sharp in the key of C♯. As you move through the flat key signatures, you add flats until every note is played flat in the key of C♭. It may be of some comfort to know that composers usually write in key signatures that are comfortable for the player to read. For example, D major is a very common key for string instruments to play because the open strings are closely related to the tonic, D. There are few works out there that have strings play in E♭ minor, or brass playing in E major.

Comments

0 comment