views

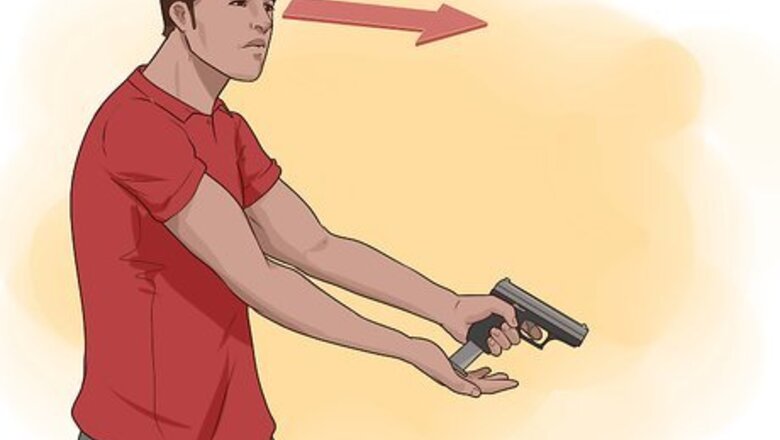

Practice reloading your pistol

You should be able to load your gun quickly 100% of the time — without looking at your pistol, your hands, or your magazines.

Emergency reload is the reload in which you have spent all the rounds from your magazine and your slide is locked back. This should all be done while keeping your gun pointed at your target. Psychologically, lowering your gun gives your intended target an advantage over you and keeps you focused on your gun rather than on your target. The technique is as follows: when the slide locks back, you want to grab another magazine (likely from a magazine pouch). As you move the fresh magazine toward the gun, eject the empty magazine letting it hit the ground (they should essentially pass each other during the drill). Place the rear of the magazine against the rear of the magazine well of the gun, align the two, and with some force (though there should be little resistance) seat the magazine using the heel of your palm; then depress the slide release.

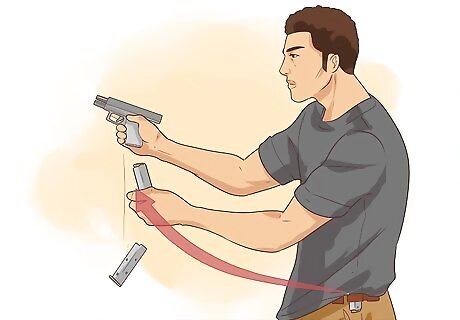

Tactical reload is the reload in which you encounter a lull in the gunfight and are able to place yourself behind cover. You know you have spent some rounds from the current magazine and want to prepare for whatever may come next. This drill can be done at the ready, since it should be done from behind cover and the other shooter (target) may be visible, but not an immediate threat. Reach to your magazine pouch (or other magazine holder — a pocket perhaps — and grab a magazine with your thumb, index finger, and middle finger. Move back to the gun and eject the partially depleted magazine into your hand, grabbing the ejected magazine with your ring finger, pinkie, and the palm of your hand. Insert the fresh magazine into the gun and tug on it slightly to make sure that it is seated in the magazine well correctly. (This is especially important when loading a magazine that is topped off.) This reload doesn't require manipulation of the slide release. This reload should be executed before you re-holster your pistol so if you need to draw again you are fully prepared.

You should be practiced enough that when you are shooting (no matter how many rounds are in the magazine), you should be able to feel when the handgun is empty. The slide has two separate actions every time a round is fired; after the last round is fired you will only feel the first action, ultimately there is less muzzle flip. The quicker you are able to reload the magazine, the better. After this, you execute an emergency reload.

Train yourself

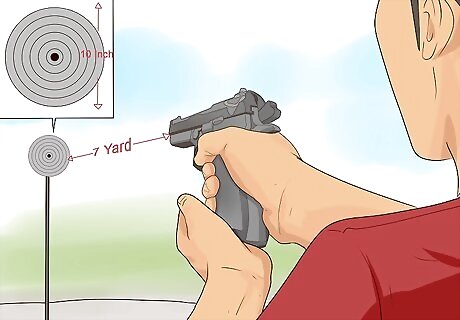

Position yourself about 7-yards (the distance the FBI determined a man could move in a second and a half — about the time it takes to draw a pistol and fire) away from a large (10+ inch) target. In a lowered gun stance (ready position), pull your gun up, as quickly as possible, to firing position and focus hard on the front sight of your gun, wait until you see a bit of the front sight between the rear sights and pull the trigger (this is called flash sighting). You should be able to land a hit in the 10-inch target every time. If you are missing try going a little slower. The key is to practice perfectly, and the speed will come naturally.

The next stage is to put bursts into the target. Take a few steps back (go for 10 yards). Do the same things as before, but this time, put two or three shots quickly into your target, between each shot, get the flash sight again. Once you are able to get to firing position and put three quick shots into your 10+ inch target consistently in under a second-and-a-half, you can move on.

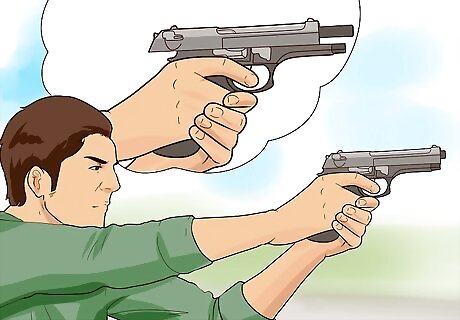

Practice with multiple targets. You want to start by setting up three or more targets a yard or two apart. Quick to firing position and go down the line. One shot at each target. Change it up: maybe try in a different order; have a friend tell you which one to shoot ("one!", "three!", etc.), but the key thing to be sure of is that you hit your target; once you are sure you can hit your target every time, try to accelerate your pace. At first when you fire move the gun with the recoil. As soon as the recoil is completed you should be on the next target already. As you get faster you can force the gun into position and be ready before the recoil is complete.

Practice while moving. While moving, you should still be able to hit targets at 10 yards (9.1 m). Set up three or more targets about a few yards apart from each other. Start about 15–18 yards (13.7–16.5 m) back. Run up to about 10 yards (9 m) (from your first target) while drawing your gun to firing position. Fire a two-shot burst, side-step to engage the next target, and so on. Each time you run the course, try to do it faster; try to pause as little as possible when shooting (even while moving you should be able to get a flash sight), the longer you pause the more accurate you will be, but in a gun fight, the clock is always ticking quicker than at the range.

Integrate the Mozambique Drill. If a friend is calling out target numbers, and they call the number of a target you have already shot, this time you go for a head shot. This is also known as "failure to stop" practice. The idea is, you have shot the target, but he isn't impressed (i.e. he is on drugs, is wearing body armor, or is just plain determined) and keeps coming, so you have to take a head shot. Read Human Targets below for more information.

Human Targets

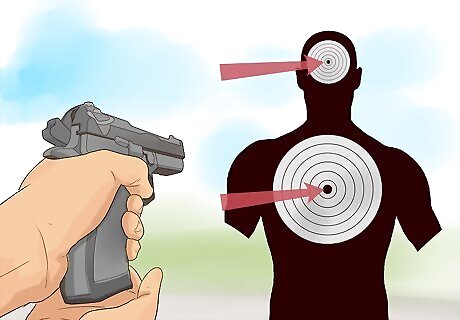

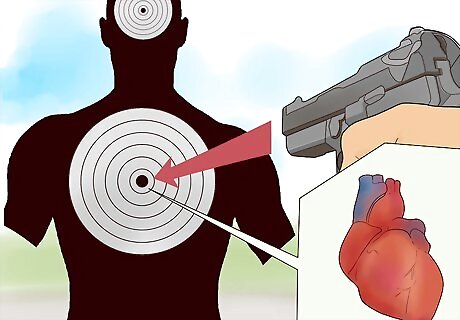

Bullet placement is much more important than the bullet itself. There are two critical areas of a human which contain major organs and vitals which, if shot, can stop a man in his tracks or kill him.

The thoracic cavity is the "center of mass" in a human. This area contains the heart, major veins and arteries, the trachea, bronchi and lungs, the esophagus, and structures of the nervous system including the paired vagus nerves. To imagine the area that this encompasses it starts above the diaphragm (just below the sternum) and makes (from a frontal view) a dome shape up to the first lateral rib. This is a pretty large target area. A shot in one area of the thoracic cavity is little different any another, unless you hit the heart. The problem with shots in the thoracic cavity is that a determined fighter or a man on drugs will be less than impressed with anything you throw at him in this area. Even if you destroy a person's heart they still have 20 to 30 seconds of full cognitive and physical ability with which they could severely hurt or even kill you. Additionally the heart is a very small target and completely destroying the heart with one bullet is nearly impossible, which means that they will likely have even more time before their eventual fate is achieved. For all these reasons, many have the self-defense rule: "shoot until the threat ends." But you must determine for yourself what your protocol will be. Body armor is also a factor. Just hitting a man in the chest (unless you hit him in the exact same place every time) is just going to deplete your magazine. Bullet penetration is a very key factory in bullet selection. This penetration does a few things for you. At less than optimal angles, the bullet will still reach vitals, and it will give your bullet a chance to possibly hit their spine, which (depending on where it lands) can incapacitate them completely or at least part of their body, enough so you may be able to get away.

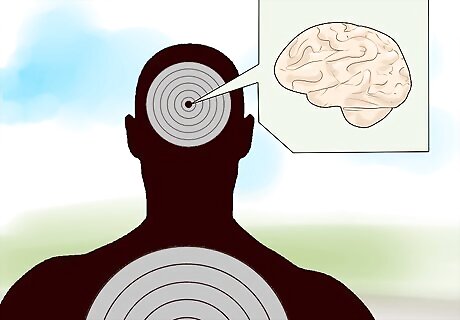

The second major area is the cranial cavity. This area is much simpler; it contains the brain and upper spine. While the brain is an obvious target, there are still some considerations in shot placement. The front of the cranium (above the eyebrows) is one of the hardest bones in the body, it is also not a flat target (it is angled back slightly, or on the sides: angled to the side). There have been instances where bullets have ricocheted off a person's forehead. Luckily, just below this bone (below the eyebrows), down to the top of the upper-jaw is a very soft area with cartilage and holes which lead directly to the lower brain, the medulla oblongata, and the upper spine. The brain is the largest target, and a bullet in there will mean lights out, but flinching and minor movements have been known to occur when a brain shot is incurred. The medulla oblongata and the upper spine is how those flinching signals are sent to the body. A bullet through either one of those, and there is no way the body might accidentally pull a trigger or move in some other potentially detrimental way. In a situation which requires the immediate and unquestioned incapacitation of a person, a shot through an approximately 3-inch (above the upper-jaw to eyebrows) by 5-inch (the outside edges of the eyes) window in the head is essential. This 3x5-inch area is about the same no matter what angle the person is facing you at (from the rear and the sides it is about the same size and about the same level on the head).

For practice, replacing the circular chest target with a dome-shaped 11x7-inch target and the head with a 3x5-inch target will get you a more realistic targeting area. When scoring (to compare your improvements) or competing, a shot breaking the line of either cavity is good. The size of the grouping should matter less than getting the hits in quickly; and when shooting at the cranial cavity, only a guaranteed shot should be taken (you should always take more time for a cranial shot than a thoracic shot). But keep in mind, "remember your worst day at the range, you will be twice as bad when you are in a gun fight." So a general rule of a hand-sized grouping in the thoracic is optimal.

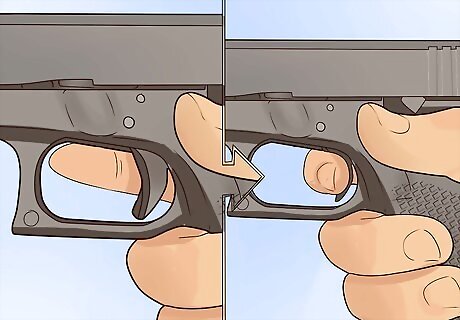

Rapid Fire

Glock and other Constant Double Action (DAO) pistols (such as QA Walthers, LEM, and DKA triggers) have a trigger which has a reset-point after the gun has been fired. Fire a round at your target; now, slowly release the trigger until you hear a click, and resistance on the trigger is lessened. At this point you can pull the trigger again. This not only allows you to be more accurate while doing single-shots (due to the shorter trigger pull), but when you get your finger used to the motion, it is the best way to shoot the gun quickly.

Most other pistols (single-action—SA, double-action—DA, double/single-action—DA/SA) are a bit more standard. You have to release the trigger completely before it can be pulled again. SA and DA/SA will be easiest for this drill, as they will have lighter trigger pulls than their DA (or DAO) counterparts.

After you have your trigger pull down. The first thing is to practice (at close range — 4-8 yards) shooting the gun as fast as possible. The faster you can pull the trigger the more options it leaves for you.

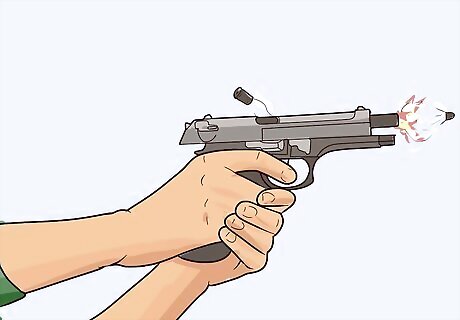

The process of the gun when you fire a bullet is such: bullet is fired, slide racks back, shell ejected, as the slide moves forward the rest of the gun (frame, barrel, etc.) raises (this is called muzzle flip), as soon as the slide is back in battery (full-forward) the gun can fire again. The final slide position happens before the gun has gone back to its original position in your hands.

If you pull the trigger before the gun is at rest in your hands you will shoot higher than the first bullet. If you wait too long, the gun will actually bounce below the original position, firing during that stage will cause the bullet to land low. You can either wait a bit longer (but that removes the word "rapid" from this drill), or you can time the firing to when the gun is falling past the rest position. You can also increase the cycle speed of gun in your hands by getting a tighter/firmer grip on the gun (too firm for accurate single-shot shooting). If you do this, timing is more important, but it allows you to shoot faster. Note that each gun, and each caliber will have totally different cycle times, so being practiced with few handguns is best. If you get the timing wrong, you will find hitting a target consistently even at 5 yards (4.6 m) can become difficult. If your bullets are hitting high after the first one, try shooting a bit slower. You can alternatively try tightening your grip on the gun. If you are shooting low, either shoot faster or loosen your grip on the gun.

With some practice you will find you can do 10–12 inch (25.4–30.5 cm) groupings at 7 yards (6.4 m). Once you are able to do that, or get close to that, you can add other drills: setup two or more targets. Fire four or five rounds at one target, then turn to the next target and so on. This combines one of the earlier-mentioned shooting drills and the rapid fire drill.

Other Drills

This drill can be added prior to any other drill. It is designed to get your heart rate up and maybe some adrenaline going which will give you a mild tunnel vision effect. Before you do a drill, with your firearm securely holstered, do 20 or more push ups. Go until you have a bit of a burn and you are getting out of breath. Jump up and do your drill as soon after as possible. You will find that acute aiming is much more difficult, though general flash sight aiming shouldn't be too much different; this is why it is so important.

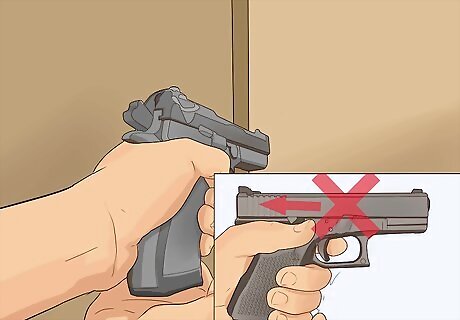

Most semi-automatic pistols will not fire if the slide on the gun is not in battery (full-forward) position. This becomes a problem if your pistol is resting against something or the front of the gun is pressed into something soft. A simple drill to keep the bad guy off of your gun in a close quarter situation is to put your support arm straight in front of your chest bent at a 90-degree angle. This keeps the bad guy off you, while your firing arm is lowered near your hip. For practice: a tall target you can lean up against your arm and fire into it is good (make sure the target is soft, so the bullets don't ricochet and it doesn't splinter — make sure you shoot straight forward so you don't hit your arm). A couple times is all you need with this drill, just to give you the feel.

Charging a bad guy seems like a stupid idea in most cases, but if the bad guy is reloading, or otherwise distracted, it can be of great benefit (you may be able to catch them by surprise or disarm them). Have a center-chest-sized target (10+ inches) setup 15–20 yards (13.7–18.3 m) away. Start your sprint at it, when you feel you are close enough to hit the target while moving, slow down to a crouched walk with your knees slightly bent (to keep your upper body smooth) and shoot the target. Add different things while running: have a friend tell you when to start shooting (at random times). Or start running at the same time a friend starts reloading. Have the friend yell when he is done to let you know to start shooting. It can become a reloading vs. sprinting contest (it will also give you an idea of how long a reload feels like if you need to rush someone). If your location allows, stand 15–20 yards (13.7–18.3 m) away from your target. Have another person stand well off to the side pointing at a different target. The person standing to the side will have one round in the chamber and an empty magazine, with a loaded magazine in easy access (i.e. magazine pouch). You should have your gun out at and the ready. The other person will fire; you start running at your target. When you are close enough to get good hits, you shoot; if the other person is able to reload and fire at his target before you shoot, he wins. It is best (for safety reasons) for the other person to be aimed and shooting at a target which is different direction than yours, so at no time will one person be in front of someone else's muzzle. Additionally, you can try reloading while running at the target, then shoot the target when you are done (this is the most advanced version of this drill).

Comments

0 comment