views

Using Quick Rules

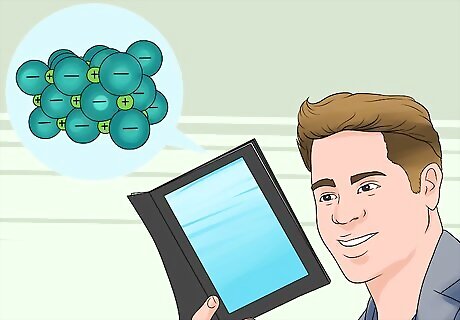

Learn about ionic compounds. Each atom normally has a certain number of electrons, but sometimes they pick up an extra electron or lose one through a process known as electron transfer. The result is an ion, which has an electric charge. When an ion with a negative charge (an extra electron) meets an ion with a positive charge (missing an electron), they bond together just like the negative and positive ends of 2 magnets. The result is an ionic compound. Ions with negative charges are called anions, while ions with positive charges are cations. Normally, the number of electrons in an atom is equal to the number of protons, canceling out the electrical charges.

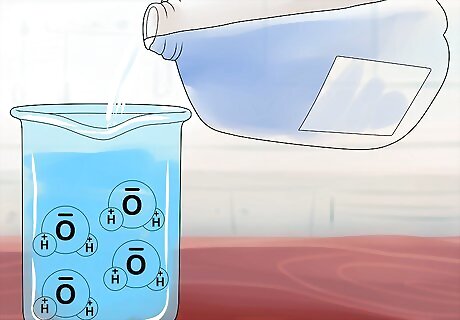

Understand solubility. Water molecules (H2O) have an unusual structure, which makes them similar to a magnet: one end has a positive charge, while the other has a negative. When you drop an ionic compound in water, these water "magnets" will gather around it, trying to pull the positive and negative ions apart. Some ionic compounds aren't stuck together very well; these are soluble since the water will pull them apart and dissolve them. Other compounds are bonded more strongly, and are insoluble since they can stick together despite the water molecules. Some compounds have internal bonds that are similar in strength to the pull of the water. These are called slightly soluble, since a significant amount of compounds will be pulled apart, but the rest will stay together.

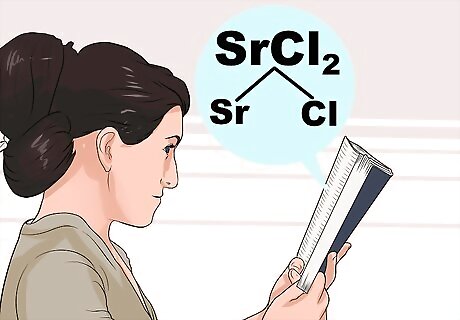

Study the rules of solubility. Because the interactions between atoms are quite complex, it's not always intuitive which compounds are soluble and which are insoluble. Look up the first ion in the compound on the list below to find out how it usually behaves, then check the exceptions to make sure the second ion doesn't have an unusual interaction. For example, to check Strontium Chloride (SrCl2), look for Sr or Cl in the bold steps below. Cl is "usually soluble," so check underneath it for exceptions. Sr is not listed as an exception, so SrCl2 must be soluble. The most common exceptions to each rule are written beneath it. There are other exceptions, but you are unlikely to encounter them in a typical chemistry class or laboratory.

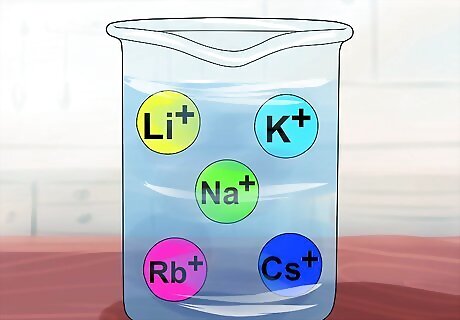

Recognize that compounds are soluble if they contain alkali metals. Alkali metals include Li, Na, K, Rb, and Cs. These are also called the Group IA elements: lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium, and cesium. Almost every single compound that includes one of these ions is soluble. Exception: Li3PO4 is insoluble.

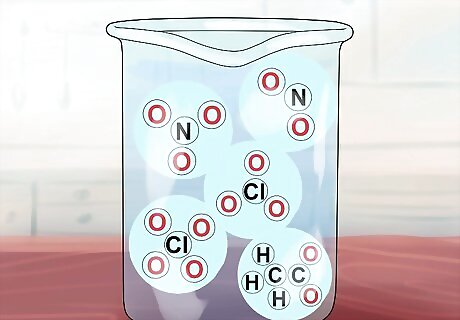

Understand that some other compounds are soluble. These include compounds of NO3, C2H3O2, NO2, ClO3, and ClO4. Respectively, these are the nitrate, acetate, nitrite, chlorate, and perchlorate ions. Note that acetate is often abbreviated OAC. Exceptions: Ag(OAc) (silver acetate) and Hg(OAc)2 (mercury acetate) are insoluble. AgNO2 and KClO4 are only "slightly soluble."

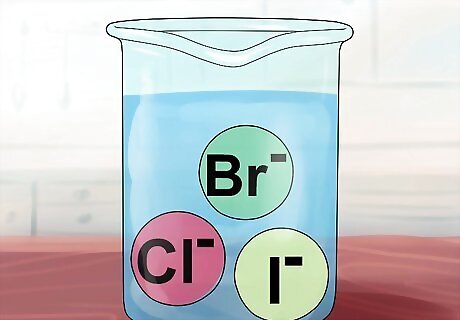

Note that compounds of Cl, Br, and I are usually soluble. The chloride, bromide, and iodide ions almost always make soluble compounds, called halogen salts. Exception: If any of these pair with the ions silver Ag, mercury Hg2, or lead Pb, the result is insoluble. The same is true of less common compounds made from pairing with copper Cu and thallium Tl.

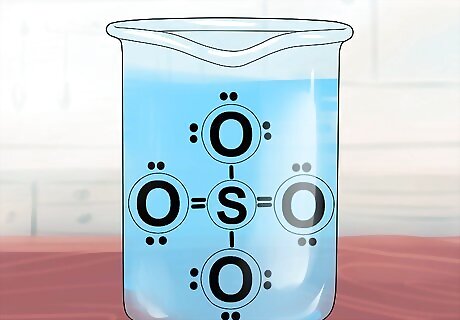

Realize that compounds containing SO4 are usually soluble. The sulfate ion generally forms soluble compounds, but there are several exceptions. Exceptions: The sulfate ion forms insoluble compounds with the following ions: strontium Sr, barium Ba, lead Pb, silver Ag, calcium Ca, radium Ra, and diatomic silver Ag2. Note that silver sulfate and calcium sulfate dissolve just enough that some people call them slightly soluble.

Know that compounds containing OH or S are insoluble. These are the hydroxide and sulfide ions, respectively. Exceptions: Remember the alkali metals (Group I-A) and how they love forming soluble compounds? Li, Na, K, Rb, and Cs all form soluble compounds with the hydroxide or sulfide ions. In addition, hydroxide forms soluble salts with the alkali earth (Group II-A) ions: calcium Ca, strontium Sr, and barium Ba. Note that the compounds resulting from hydroxide and an alkali earth do have just enough molecules that stay bonded to sometimes be considered "slightly soluble."

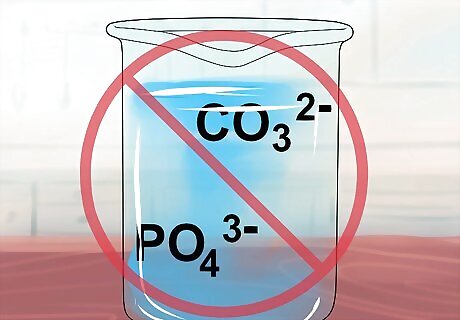

Understand that compounds containing CO3 or PO4 are insoluble. One last check for carbonate and phosphate ions, and you should know what to expect from your compound. Exceptions: These ions form soluble compounds with the usual suspects, the alkali metals Li, Na, K, Rb, and Cs, as well as with ammonium NH4.

Calculating Solubility from the Ksp

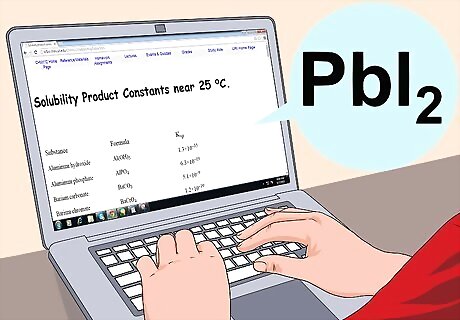

Look up the product solubility constant (Ksp). This constant is different for each compound, so you'll need to look it up on a chart in your textbook. Because these values are determined experimentally, they can vary widely between charts, so it's best to go with your textbook's chart if it has one. Unless otherwise specified, most charts assume you are working at 25ºC (77ºF). For example, if you're dissolving lead iodide, or PbI2, write down its product solubility constant.

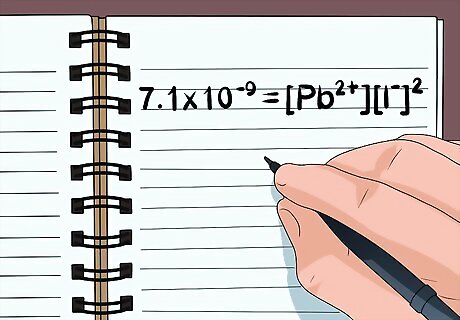

Write the chemical equation. First, determine how the compound splits apart into ions when it dissolves. Next, write an equation with the Ksp on one side and the constituent ions on the other. For example, a molecule of PbI2 splits into the ions Pb, I, and a second I. (You only need to know or look up the charge on 1 ion, since you know the total compound will always have a neutral charge.) Write the equation 7.1×10 = [Pb][I] The equation is the product solubility constant, which can be found for the 2 ions in a solubility chart. Since there are 2 I ions, I is to the second power.

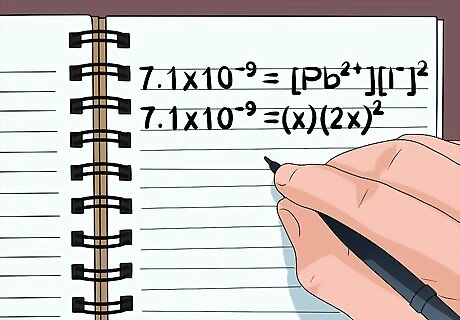

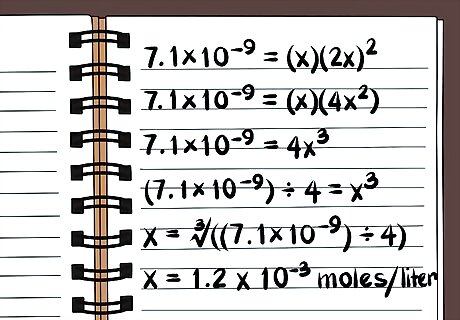

Modify the equation to use variables. Rewrite the equation as a simple algebra problem, using what you know about the number of molecules and ions. Set x equal to the amount of the compound that will dissolve, and rewrite the variables representing the numbers of each ion in terms of x. In our example, we need to rewrite 7.1×10 = [Pb][I] Since there is 1 lead ion (Pb) in the compound, the number of dissolved compound molecules will be equal to the number of free lead ions. So we can set [Pb] to x. Since there are 2 iodine ions (I) for each lead ion, we can set the number of iodine atoms equal to 2x squared. The equation is now 7.1×10 = (x)(2x)

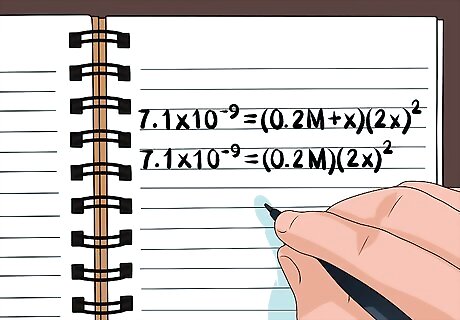

Account for common ions, if present. Skip this step if you are dissolving the compound in pure water. If the compound is being dissolved into a solution that already contains one or more of the constituent ions (a "common ion"), however, the solubility is significantly decreased. The common ion effect is most notable in compounds that are mostly insoluble, and in these cases you can assume that the vast majority of the ions at equilibrium come from the ion already present in the solution. Rewrite the equation to include the known molar concentration (moles per liter, or M) of the ions already in the solution, replacing the value of x you used for that ion. For example, if our lead iodide compound was being dissolved in a solution with 0.2 M lead chloride (PbCl2), we would rewrite our equation as 7.1×10 = (0.2M+x)(2x). Then, since 0.2M is such a higher concentration than x, we can safely rewrite it as 7.1×10 = (0.2M)(2x).

Solve the equation. Solve for x, and you'll know how soluble the compound is. Because of how the solubility constant is defined, your answer will be in terms of moles of the compound dissolved, per liter of water. You may need a calculator to find the final answer. The following is for solubility in pure water, not with any common ions. 7.1×10 = (x)(2x) 7.1×10 = (x)(4x) 7.1×10 = 4x (7.1×10) ÷ 4 = x x = ∛((7.1×10) ÷ 4) x = 1.2 x 10 moles per liter will dissolve. This is a very small amount, so you know this compound is essentially insoluble.

Comments

0 comment