views

Exploring Ways to Describe Emotion

Say it with a physical response. Imagine watching someone experiencing this emotion. Does he clutch his stomach or hide his face? Does he try to grab your shoulders and tell you what's happened? In narrative, the most intimate way to communicate a feeling is by describing the state of the body. Imagine yourself feeling this emotion. How does your stomach feel? When a person experiences a strong emotion, the amount of saliva in his mouth changes, his heart rate changes, and chemicals are released in his chest, stomach, and loins. However, be careful not to overstep your boundaries as to what the character is aware of. For example, "Her face turned bright red in embarrassment," isn't something the character would know. However, "Her face burned as they laughed and turned away," works wonders.

Use dialogue between characters. Using actual conversation can put the reader much deeper and more involved into the story than, say, "She frowned at how aloof he seemed." Using dialogue is actually in the moment as opposed to taking a second to step outside and narrate the story. It keeps the flow going and is true to the character – if your dialogue is right. Next time you're tempted to write something like, "He smiled at how she looked at him." Instead, go for, "I like the way you look at me." It has investment. It feels personal, genuine, and real. You can also use thoughts. Characters can talk to themselves, too! "I like the way she looks at me," has a similar power, even though it goes unspoken.

Use subtext. Often, we're not entirely aware of how we're feeling or what we're doing. We nod and smile while our eyes are burning with rage or we inhale a sharp intake of breath. Instead of addressing these layers outright, imply them. Have your character nod and agree politely while she's shredding a napkin to pieces. Your story will keep the layers intact. This can help with conflict and tension especially. It can also help with subtler forms of conflict, like characters who are uncomfortable with emotion, unwilling to open up, or waiting for an opportunity to express themselves.

Talk about the character's senses. When we're feeling particularly emotional, sometimes certain senses become extra-sensitive. We're more likely to lounge in the scent of a lover, more likely to hear every creak when we're home alone. You can use these elements to convey emotion without even needing to touch on it. Saying, "Someone was following her so she quickened her pace," gets the point across, but it's not engaging. Instead, talk about how she could smell his cologne, how he stank of cold beer and desperation, and how the jangle of his keys quickened with every step.

Try the pathetic fallacy. Contrary to what its title may suggest, this has nothing to do with being pathetic. This is the term for when the environment reflects the prevalent emotions of a scene. For example, when the tension is building between rivals, a window breaks (this should have a cause unless one of these people is telekinetic). A student is relaxing after acing a dreaded examination and a breeze rustles the grass. It's a little cheesy, but fun, and it's effective if you're not heavy-handed or trite. Employ this writing maneuver very carefully and selectively. If you do it all the time, it loses its efficacy. It can also be a little unbelievable. Try using this literary technique without even touching on emotion – perhaps even before introducing individuals. This can set a scene and offer a parallel to the reader that they can put together once they've delved a bit into the story, adding an extra layer of intricacy and complexity.

Talk in terms of body language. Try this: think about an emotion. Think about it long and hard. Think about the circumstances of the last time you felt it. Now, start talking about the emotion. What it felt like, what the world seemed like. Once you're deep into this exercise, note your body. What are your hands doing? Your feet? Your eyebrows? How is this emotion made clear in terms of your body language? When's the last time you walked into a room and could read the person you saw within seconds upon entering? Probably not that long ago; in fact, probably a number of examples have cropped up in your head. Emotions don't need to be spelled out or even thought – our bodies do it for us. Spend the next few days noticing your friends' and family's micro expressions. Those little fleeting giveaways that you would never notice if you weren't really, really paying attention. It's those moments that can bring your narration to life.

Exploring How an Emotion is Felt

Define the situation. Emotions are reactions; they have causes. You'll only be describing emotions in a vacuum if the feeling is due to some hormonal imbalance or repressed memory. Go through the details of the situation. What part of it is your character reacting to? What parts are they even aware of? In these cases, observable phenomena such as pacing or snapping at innocuous comments can convey the mindset and build to an emotion just fine. Use these as jumping off points for grander displays – or you can even let them speak for themselves. Stick to visual or tactile imagery. It's not what the situation is presenting, it's what the character notices. Only minute details should be laid out if the character is, for some reason, hyper-aware.

Use your own personal experience. If you have felt the emotion you're trying to describe, this is the best raw material. Where did it come from? Think of what made you feel the emotion. As you felt it, you weren't thinking, "Oh, I'm sad." You were thinking, "What am I going to do with myself?" You caught yourself feeling no urge to partake in your environment. You didn't notice your trembling hand; instead, you felt so unsure you couldn't stop yourself from shaking. This raw experience will give you details imagination never could. If it was the cumulative effect of a particular situation, you may want to describe that situation as you subjectively experienced it, either as practice, to pin down what led to the feeling, or as an end in itself. If it was a single moment or a single item that struck you, use details from that image to recreate the feeling. If you haven't felt the emotion, try to approximate it from related feelings or less intense instances of that emotion.

Know how your character would and wouldn't respond. Emotions are abstract concepts that different people find and experience different ways. While one person might deliver a Shakespearean sonnet to convey their personal torture, another might say, "I don't want to talk about it" through gritted teeth and an averted gaze. Really, the two could be saying the exact same thing. So, in some situations, you need not describe the emotion at all. You can describe the scene, another character's face, or the next thoughts, which may do the "emotion describing" for you. A sentence like "The world faded away, drained of all color but him" exactly states how the character feels without explicitly saying it.

Show, don't tell. In your work, you should be painting your audience a picture. They should be able to emerge from your words with an image burned onto the backs of their eyelids. It's not enough to tell them what's going on – you've got to show them. Let's say you're talking about the perils of war. You wouldn't give dates and statistics and talk about the strategy each side is employing. You mention the burnt socks littering the street, the heads of dolls piling up on the curb, and the stream of screams getting extinguished day by day. This is both an image and a visceral feeling your reader will emerge with.

Don't shy away from simplicity. This article will riddle you with insistence that you shouldn't state an emotion explicitly, but there are shades of grey. Only novel and pertinent information should be communicated in this way, but a rare, simple statement can be much better suited to some descriptions than a whole paragraph. Don't be afraid to say less sometimes. A character having a dawning realization, thinking to themselves, "I am sad." can be a very moving thing. That moment of emotional awareness could strike them and it could be surmised in those three words. Some characters may experience emotion in soliloquies, some in three short words, and some not at all. No way is wrong.

Editing Your Literary Work

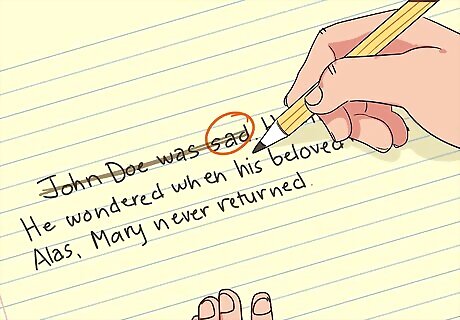

Go through and cut every time you name an emotion. Every time you talk of a character being "sad" or "happy," or even "miserable" or "ecstatic," cut it. Chop it right out; you don't need it. It's not driving your story ahead or giving it any momentum. These things can and should be made clear in other ways. Unless it's in dialogue, it needs to be scrapped. In other words, another character could ask, "Why are you so sad?" but the character at hand would never explore their world confined by the titles given to emotions. After all, "sad" or "miserable" are just words. If we called them "gobbledegook," it'd mean the same thing. These terms have no resonance emotionally.

For your first draft, replace it with a simple action or image. Even "she glanced over and grinned," is a good start for your first draft. Anything that moves away from, "she was happy" is a step in the right direction. This will evolve and grow over the course of your writing; right now, you just need something to hold it together. This is just laying the foundation of your story. Its purpose is just to be cohesive and hold the story together. You'll change everything later once you have the story pieced together.

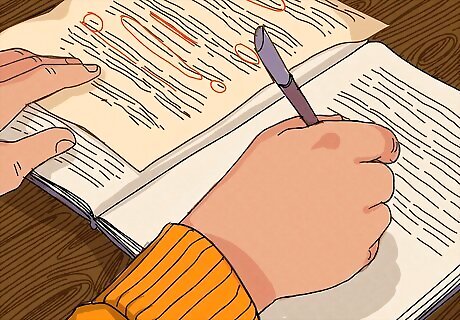

For your second draft, get more detailed. Why did she glance over and grin? What was she thinking to herself? Was she thinking that the boy in the corner was kind of cute? Did he remind her of anyone? What was the motivation for the emotion? Explore the techniques discussed above. Painting an image through dialogue, subtext, body language, and the senses will create a 360-degree picture for your audience to feel fully engrossed in the story. Instead of "she was happy," your audience will actually know how she feels.

Avoid cliches and stock phrases. They won't drive your story forward -- they're too trite to do so. Few things are less communicative than "I was so happy I could die" or "I felt my world falling apart." If your character's that happy, have her spontaneously hug someone and then laugh aloud. If you were that upset, say what happened. People can understand the emotional impact of any major event; if you describe it, they'll know what it does to the people involved. Never end a clear, intimate description of an emotional event with a cliché. If you've done the job of communicating the emotions, you've done it. Don't feel the need to summarize. Stay in character. The personality you're working with may be the cliché type – just don't end it how it normally ends. The terrible thing about cliches is that people don't actually say them when they're being genuine. But after explaining how your character feels and after her spontaneous hug, if it's in her personality, have her say, "I'm so happy I could just poop a rainbow!" It may be fitting. But again, only if she's that type.

Stay appropriate. Be as graphic or tactful as the rest of your piece is. Use metaphors and images that fit thematically with the content, and make sure (especially in first-person) the language and images you use fit the character(s). No talk of velocities or crossed wires in the Old West! If you're speaking, be as frank or vague as your companions make you feel. Not only should you keep the character in mind, but the keep the character in that specific situation in mind. There may be outside factors that are affecting their judgment, senses, and even ability to react, think, or process emotion.

When you're nearly finished, tune into the emotion you're writing about. Spend some time listening to music, reading poetry, or reading stories of authors that write on similar themes. When you're immersed in the emotion, go back and read your story. Does it feel aligned with how you were feeling? Are there any incongruencies? Does anything strike you as disingenuous? If so, scratch it and get back to the drawing board. If a particular emotion is eluding you, give yourself time. The next time you run into that emotion, bust out your notebook and take note of your senses, thoughts, and body. This will get you as close as possible to the truth of this emotion. Nothing is better than first-hand experience. From there, your story will write itself.

Comments

0 comment