views

Building a Character

Think about personality and role in the story. What does your character do for the story? What type of personality will they have? Start sketching out their rough personality and general role. A clear personality (as opposed to "does whatever") gives your character a stronger presence in the story. A list of adjectives (e.g. caring, perceptive, perfectionistic, anxious) is a good start, but it isn't nearly enough for a complex character. A strong character has a detailed history and present.

Consider the character's struggles. One thing that interests readers is how a character deals with pain. What causes your character emotional pain? Do they suffer from an abusive family, bullying, regret over bad decisions, perfectionism, a mental illness, et cetera? What is your character afraid of? What upsets them? Some beginners overload on tragedy, thinking "more pathos means more interesting." However, too much can cause readers to lose interest. Focus on one or two things that hurt your character. One or two intense struggles are more compelling than 5 different problems. Try researching the problem(s) your character faces. For example, if your character is self-conscious about being deaf, read from Deaf people, their internal struggles, and how they learned to accept themselves. Tip: Readers tend to sympathize with characters who go through hardships they don't deserve (just like they tend to dislike characters who get accolades they don't deserve). If you want readers to like your character, try throwing them into some tough situations that aren't their fault.

Ask how your character deals with their pain. Do they hide their vulnerability, or share it? How do they cope on bad days? Consider which strategies (healthy or unhealthy) your character has developed to deal with hardship. Who do they open up to? If it's hard to open up, why? What makes it scary to them? On a bad day, how does your character handle things? Be socially conscious when discussing harmful coping mechanisms. For example, your character might do harmful things, like excessive drinking or acting possessive/controlling to their partner. To avoid glorifying bad behavior, show the negative consequences of these. Your character should be held accountable for their actions.

Build a detailed backstory. Consider the family and living situation your character had growing up, what problems they faced in childhood, and how this shaped who they are today. While the reader may not need to know all these details, it can help you understand your character as a person. Example: Rosario grew up in a large family that spoke endlessly of "hard work" and "pulling yourself up by your bootstraps." Determined to meet her parents' expectations, Rosario worked endlessly in school, but kept failing while her peers succeeded. Her teachers called her lazy, and she concluded she was broken. She was hospitalized at age 22 for burnout so severe it nearly killed her. Her subsequent ADHD diagnosis offered some relief, and an idea she wasn't defective. But she still struggles with feelings of inadequacy, and fears that no one will take her needs seriously, giving her difficulty opening up to others.

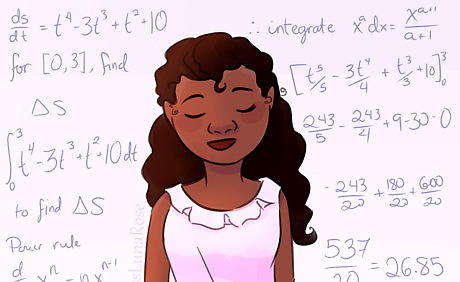

Give your character clear strengths. A character built of only pain and weakness may end up feeling flat instead of compelling. To build a more rounded character, work on your character's strong points as well. Give them opportunities to shine. "Strengths" are more than school- or job-related skills like "math" and "fixing cars." Your character may also be compassionate, empathetic, good at problem-solving, a quick thinker, or other things that aren't tested at schools. Give your character opportunities to help others, or help progress the plot in positive ways.

Balance strengths with one or two real flaws. A flaw isn't something trivial like "she's clumsy" or "he can't bake." It's an issue with priorities that causes your character to make bad decisions. Maybe they're too conflict-avoidant, pushy, impulsive, or stubborn. In a detailed and nuanced story, your character should be in the wrong sometimes. This makes them interesting and human. "She's sassy" isn't a flaw. "She gets herself in trouble by picking verbal fights with people" or "she flies off the handle and yells at people when they don't deserve it" are flaws Avoid reinforcing stereotypes or biases by mislabeling harmless traits as flaws. For example, "the effeminate boy learns to act more manly" or "the autistic woman learns to stop fidgeting in public" aren't actually growth arcs. Growth means adjusting your behavior in healthy ways, not hiding who you are or making yourself uncomfortable for others' sake. Tip: Tie your theme to the flaw(s) of one or more major characters. A big part of your story's message comes from them managing and confronting these issues.

Avoid stereotypes. If your character falls into common stereotypes (greedy Jew, sexy Latina, burdensome disabled person), the lazy writing will make readers stop seeing the character as a three-dimensional person. When writing diverse characters, read from people like your character. For example, if you're writing a Muslim character, read personal essays by Muslims about their lives, and articles on how (not to) write Muslims in fiction. Make your character unique. For example, black teens in poor urban areas are often stereotyped as "thugs" who get into trouble. But maybe your character has a passion for singing, and dreams of going into theater. Showing what makes them different helps build a strong story. Try to surprise your readers by subverting their expectations of what the character "should" be.

Give the character a secret. This can add layers of nuance and suspense to your story, especially if the secret is in danger of coming out, or the character is struggling with how to deal with the secret. Emotions can be kept secret: fears, desires, et cetera. How does the character feel about the secret? How far will the character go to keep it from coming out?

Choosing Superficial Aspects

Develop their appearance. Your character's appearance will be partially influenced by genetics, and partially by their personality. They will choose hair, piercings, clothes, and accessories. For example, a shy girl might have long hair that hides her face, while a practical girl might prefer short hair that is easy to wash. Try doodling your character (even if you aren't good at art) to help you imagine them and how they might look.

Figure out which phase of life they are in. How much wisdom and experience do you want them to have? How old is your target audience? Exact age isn't important, but general stage of life ("middle school," "close to retirement age," "just started first job") matters. Kids and teens may like reading about characters who are a little older than they are, especially as they think about what growing up will be like for them.

Choose a name with subtle meaning, if any. Many beginning writers pick overly obvious names, such as "Brick Stronghelm" for a tough character, or "Raven Nightfall" for a mysterious girl. This is as subtle as getting hit over the head with an anvil. Look for name meanings that are more subtle, and don't be afraid to be ordinary. After all, most people have ordinary names. For example, the story "Silent Voice" features the main character "Claire Fields." The story is about a girl developing her voice, so "Claire" suggests clarity. "Fields" is a common last name that involves peaceful nature imagery. Use baby name websites for ideas. Make sure that the names seem reasonable for the ethnicity. For example, "Nazari" would be a good last name for a Middle Eastern character, whereas "Kimikho" would be an unusual first name for a white girl who lives in Montana.

Telling an Interesting Story

Choose a goal for your character. Now that you have your character template, work on keeping their story compelling as the plot moves forward. Your character should strive for something over the course of the story. Consider what the character wants, and how they try to achieve it. To make it even more interesting, make the stakes high. Make it clear what the consequences of failure would be. For example, Tara is offered a morally questionable deal that would give her a lot of money. She balks initially, but then learns that her family is in financial trouble and may lose their house—the home that her dead mother raised her in. Tara needs money, or she will lose her childhood home forever. This goal pushes her to do things she otherwise wouldn't.

Keep your character proactive. They shouldn't just react to whatever is around them: they should try to take control of situations, strive towards their goals, and push the plot forward. For example, say your character is in a convenience store when it is robbed. A passive character would wait for the robbers to leave or the police to come. A proactive one might help others hide or leave, or even try to stop the robbers. This makes for a more interesting story.

Challenge your character over the course of the story. Make your character work for what they want. Have their flaws (impulsivity, indecisiveness, failure to communicate, etc.) work against them. Readers like to see characters being pushed hard, and how those characters react to difficult situations. Make them confront their demons. Make them wonder if they'll fail.

Consider whether the character grows from their faults. Depending on the character's role in the story, you may decide to have the character learn something. You need to (1) establish the character's flaw, (2) show the flaw hurting the character, and (3) show the character learning to move beyond the flaw. This shows character growth. Character arcs make a compelling part of a story. Example: Rayquan was bullied as a child, and learned to run and hide from the bullies. So he hides from problems, and he denies that they need to do anything about the villain in the story. Then the villain kidnaps his brother. Rayquan goes after his brother, learning to face problems head-on instead of only hiding.

Build relationships with other characters. How does your character respond to others? Who do they value (and dislike)? What does this say about your character? An interesting character isn't necessarily alone: they interact with others in unique ways.

Have your character do things that other characters wouldn't. This shows how your character (and their situation) is unique. Let your character test extremes and push limits. Show them doing things that different characters wouldn't do. This defines who they are and what they value.

Expose hidden layers over time. You, the writer, will come into the story knowing a lot about your character. The reader will know nothing. Let information be teased out over time. This lets them guess and wonder, motivating them to learn more and keep reading. Example: In chapter 1, Ann is closed-off, brusque, and secretly kind. In chapter 3, she gets angry when asked about her family. In chapter 4, she talks about her fears about being a good mother, and is kind to a child. In chapter 6, she reveals her mother was abusive. In chapter 8, Ann's refusal to communicate nearly gets her killed when she storms off and is in a car accident with no one knowing how to find her. In chapter 9, she starts opening up more to her husband.

Comments

0 comment