views

X

Research source

We’ll help you understand exactly what the fawn response is and why it happens. Then, we’ll give you the key signs that indicate you have a chronic fawn response, as well as how to start healing from it.

- The fawn response is the strong urge to please someone in order to avoid conflict, or even for your own survival.

- The fawn response is often caused by narcissistic parents or neglect in someone’s childhood. It’s also used as a last resort when other responses fail.

- Signs of a habitual fawn response include an inability to say “no,” a need for validation, and a tendency to withdraw in social situations.

What is the fawn response?

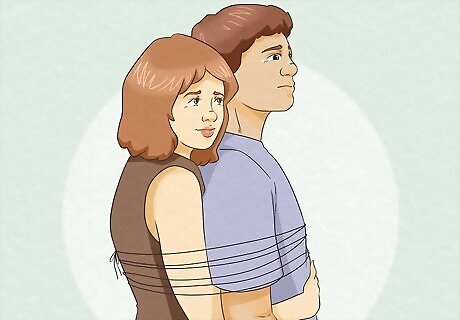

The fawn response is the urge to please in order to avoid conflict. Sometimes, when a person feels they’re in danger, they’ll try to please their physical or emotional attacker in order to avoid harm. They hope that by making the person who’s hurting them happy or comfortable, the attacker will stop hurting them. It’s often a last resort, when other survival strategies have failed, or the victim doesn’t feel that they have any other option. The response is named for the way young deer make themselves small to avoid attracting the attention of predators, and very rarely attempt to fight back. The fawn response was coined by psychotherapist Pete Walker, who specializes in complex trauma responses and PTSD.

The fawn response is one of the 4 main trauma responses. A trauma response is the way a person acts when facing danger, abuse, or something they think poses a threat. They often analyze these threats based on past experiences, and react accordingly. You probably already know the 2 primary responses—fight or flight, or when a person chooses to confront the danger, or to remove themselves from the situation. The last response is “freeze,” which is when a person feels they can neither fight nor take flight, so their body simply freezes in hopes that the danger will pass.

Why do people have the fawn response?

The fawn response is often caused by childhood trauma. For some, the fawn response is a symptom of a neglectful or abusive parent. They may have learned in childhood that, instead of resisting abusive behavior from their parents, it was easier to instead to accept it or try to make themselves small in order to avoid retaliation. As they matured, however, the tendency to appease others stayed with them and became their default way to handle conflict. This often occurs when a person has narcissistic parents, who think primarily of their own needs rather than the needs of their children.

The fawn response may be caused by codependency. Codependency, or when two people rely on each other to an unhealthy degree, is often both a symptom and a side effect of the fawn response. Someone who performs the fawn response may be afraid that, if they were to fight back, the other person would abandon them altogether. For the same reason, flight isn’t an option. This is most often the case in romantic relationships in which one partner exhibits the fawn response—they often fear being left alone, and so do everything they can to please their partner.

The fawn response is often a result of immediate danger. Anyone might resort to the fawn response, regardless of their upbringing or history of abuse. We have a natural instinct that tells us that if we make our attackers or persecutors happy, then they’re less likely to cause us harm, or it might be more difficult to cause us harm. For this reason, the fawn response is often found in victims of kidnapping or prisoners of war. It doesn’t take something as dramatic as kidnapping to trigger the fawn response, though. For example, you might go to great lengths to please your boss, since you know they hold power over your livelihood.

The fawn response can be triggered by racism. Systemic or social issues may also cause a person to resort to the fawn response. When prejudice is a societal norm, someone who’s oppressed by those norms often feels like they have little choice but to try to please the bigots. If they don’t, they face the possibility of further prejudice, or even violence. This response extends to anyone who experiences societal oppression, from those with disabilities to the LGBT community.

Signs of the Fawn Response

You find it hard to stand up for yourself. If you have an impulsive fawn response, you might believe that standing up for yourself only creates more conflict, which is the very thing you hope to avoid. So when you find yourself at the receiving end of even a mild argument, you tend to agree with your attacker in an attempt to placate them. Your priority is defusing the situation, rather than making it right. Also, you may find it hard to ask for help, since you feel that asking for help may simply open you up to more occasion for abuse.

You seek validation from other people. The fawn response isn’t always a reaction; sometimes you do it even where there is no immediate threat. You may tend to be a people-pleaser as a way to garner admiration or validation. You may want to feel worthy of love if you were neglected at some point in your life. Then, when someone does get angry with you, you feel their reaction might be softened by their admiration for you.

You tend to experience anger and guilt at the same time. If you have a fawn response, your emotions tend to get mixed up, or even conflict. When someone gets angry with you, you naturally feel frustrated or angry yourself. But then, you also tend to feel guilty for feeling those emotions. Since you want to appease the other person, you see your own anger as an inconvenience for them, and so you feel bad for feeling it. This often leads to tendency to apologize excessively in hopes of placating the other person, even when you’re not at fault.

You tend to suppress your true emotions. When you rely on a fawn response in situations of conflict, it’s easier to ignore your true emotions than it is to let them show. If you were to show your anger, disappointment, hurt, or any other negative emotion, the other person may only get more frustrated, so you learn to suppress those emotions altogether. Instead, you might laugh or even smile in the face of an emotional or physical attack, as a way to express to your attacker that you’re not a threat.

Your emotions often surface in surprising ways. When you have a fawn response, you’re suppressing your true emotions to make another person comfortable. But even suppressed emotions need to be let out somehow, and when you don’t let them out naturally, they may start to show in other ways that you find alarming or unexpected. For example, continually suppressed emotions may manifest as chronic depression, or even physical pain or illness.

You care more about how others feel than how you feel. If people-pleasing is part of your fawn response, then other people’s well-being tends to take priority. You’ve internalized the idea that your own emotions are wrong or not worthwhile, and so you look to help other people feel good before you help yourself, since your own emotional responses tend to hinge on those of the people around you. For example, you might choose to miss an important event to help a friend move. You feel that missing the event is a necessary evil in order to make your friend feel good.

You have difficulty maintaining boundaries. When other people’s emotions take priority, and your own emotions are merely a reaction to other people’s emotions, you tend to have a poor sense of your own boundaries. Other people may push you around or walk over you to get what they want, and since your impulse is to please them, you’re more likely to let them do it. Most commonly, you may find it difficult to tell people “no,” which places you in difficult situations. The trouble is that the people around you may think you enjoy those situations, since you agreed to them.

You feel like nobody really knows you. When your own reactions hinge on what other people say or do, and your impulse is to make other people happy, it becomes hard to forge meaningful connections to other people. Those people only know you for the ways in which you put them first; they don’t know your actual emotions or what you truly want, personally. In fact, you may tend to shift your own preferences, wants, or goals to align with other people’s, which can cause a profound sense of alienation from your own self, or even a loss of personal identity.

You keep to yourself and fly under the radar. At its heart, the fawn response is a desire to avoid the attention of your attacker, or to divert it away. In settings where there’s no immediate danger, this often means making yourself small, such as in social settings like parties or get-togethers. You believe that the less the people around you notice you, the less likely it is that they can have negative emotions toward you. For this reason, you may also find it difficult to make new friends or open up to new people.

How to Heal from the Fawn Response

Practice identifying and self-validating your own feelings. For people with impairing trauma responses, like the fawn response, self-compassion is critical. Examining your own feelings and why you feel them helps you understand yourself and make more informed actions in the future. Any time you find yourself resorting to a fawn response, stop and ask yourself: What do I really feel about this situation? Are my true feelings reflected in my actions and words? Once you’ve identified your true feelings, validate them. Say something like, “I feel angry and hurt right now, and those are natural and acceptable things to feel. Also, boost your self-esteem to help you resist trying to please others. Throughout your day, repeat affirmations like, “I am worthy of love,” or, “My feelings matter as much as anyone else’s.”

Consider the bigger picture to get perspective. Often, we jump to the fawn response because we fear the worst-case scenario. If you feel the urge to please others, stop and ask yourself: Am I in immediate danger? Is there a genuine threat? Am I doing this because it’s right, or because I want to avoid conflict? Identifying your motivations is often the first step to altering your trauma response. If you’re in doubt, ask for help from a trusted friend or family member, and for their opinion on the situation. Often, an outside perspective is just what we need in order to gauge our own feelings.

Practice saying no without over-apologizing. The fawn response often makes it difficult to say no to other people or to turn down requests or favors. Learning to say no is a vital step in regaining your own power. If someone asks you a favor, ask yourself: Is this something I want to do? Is it a fair request? If not, say no! Start small, in situations with low stakes, and work your way up. For example, if a friend invites you out but you’re not feeling up to it, say, “I can’t tonight. Can we reschedule?” A small “no” like this helps you understand that the consequences of a “no” often aren’t the worst-case that you imagine.

Set healthy boundaries with the people around you. Setting boundaries not only helps you to develop an important sense of self-worth, but it minimizes opportunities for your fawn response to set in. Make it clear to other people what you want, what you’re capable of, and what you won’t do. Being transparent about your desires and abilities lets other people know when it’s okay to ask you for something, and what kind of behavior makes you uncomfortable. For example, if you dislike doing a certain activity with your friends, let them know. Say something like, “I find hiking hard on my body and I don’t enjoy doing it. Can we do something else this weekend?

Nurture your healthy relationships to build emotional intelligence. When a fawn response is a leftover habit from an unhealthy past or childhood, it usually results in damaged emotional intelligence—the awareness and understanding of other people’s feelings, as well as your own. Develop your emotional intelligence by spending time around people who make you feel comfortable, or people you trust. Think about how you interact, and take cues from them for how to act, yourself. Don’t be afraid to ask your close friends hard questions. Asking them things like, “How do you feel after…” or, “What would you do if this happened…” will help you get new and diverse perspectives on other people’s thinking and how others react.

Visit a therapist to talk about your past trauma. Talk to a therapist about your childhood experience, or current experiences with your fawn response. A licensed mental health professional is equipped to help you identify your trauma, why and how you respond to it, and how to move forward and heal.

Comments

0 comment