views

Use standard medical terminology throughout.

The actual charting and documentation are for other medical staff. Using uniform medical language will make it easier for specialists, other doctors, and nurses to follow your line of thinking as you work through the diagnosis. Remember, medicine is a collaborative process, and there’s always a possibility that you’ll need to refer the patient elsewhere to another doctor. Keep this in mind while you work. Avoid using any loaded or judgmental language. The patient’s integrity matters, and you don’t want anyone reading the chart to judge the patient unfairly. If you’re lucky enough to have a medical scribe, communicate what you’re doing verbally while you’re doing it—the scribe will write everything down for you.

Take an inventory of the patient’s symptoms.

Interview the patient to see what they’re experiencing. Be friendly, cordial, and reassuring. Have a conversation with the patient to see how they’re experiencing their symptoms. Ask about pain levels, note the time these symptoms are occurring, and probe to see if there’s anything the patient is doing to trigger or treat their symptoms. You may get a diagnosis just from doing this. If your patient says their foot hurts because a car ran over it, and you can see the bone protruding from the skin on their foot, you can reasonably say the patient broke a bone in their foot. Ask follow-up questions as needed based on your specialty and knowledge. Take your experience into account here. If you’ve seen these symptoms somewhere else before, use that knowledge to guide you.

Read the patient’s medical history.

Read through the patient’s file to see if there’s anything relevant. Maybe they have an allergy that could explain their symptoms. Maybe there’s an unexplained symptom from a few years back that’s related to what you’re seeing now. Regardless, you must read through their medical history to get the full picture. Ask questions as needed to understand what the patient has done in the past in regards to their current condition. Follow these chronologically backwards from the initial visit throughout the patient's history to confirm any tie-in of symptoms. Eliminate diagnoses that do not fit your patient based on their symptoms and history.

Examine the patient and perform diagnostic tests.

Perform physical examinations to get a fuller picture of their condition. Talking and reading can only get you so far. You’ll need to perform basic diagnostic tests and physically look at the patient. Be polite and reassuring—especially if you have to look at anything private or potentially embarrassing. Perform your physical exams and document your findings. The tests you choose are going to depend entirely on your specialty, but generally speaking, you should work from general diagnostic tests to more specific tests.

Create a working diagnosis.

A working diagnosis refers to your initial theory about what’s going on. Take all of this initial information you collect to form your working diagnosis. Sometimes, a working diagnosis is correct. Sometimes, it’s not. In either case, you work from this general assumption starting now and use additional tests, treatment, or follow-ups to either affirm your initial theory, or rule it out. You may go through multiple diagnoses before you actually identify the proper disease or condition.

Rule out alternative possibilities.

If there are multiple, equally-plausible theories, exclude as many as you can. Start with the easiest exams and tests that can be performed in the exam room at this moment. It’s possible that you may not be able to run some of these tests depending on your specialty or the scope of your practice, so document what tests you’ll need to order or refer the patient for. From here on out, it’s all about reframing and revising your working diagnosis until you have enough evidence to reasonably confirm your suspicion.

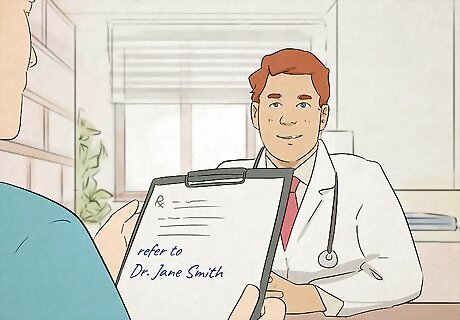

Refer the patient to specialists, if necessary.

This is the only way to get info if something is outside your scope of knowledge. Sometimes this is straightforward. If you think it’s possible that the patient is suffering from a neurological disorder and you’re a general practitioner, you’d refer them to neurologist, for example. However, you may need to refer the patient to multiple specialists if you aren’t sure which biological system is to blame here. Refer the patient to specific specialists whom you know to be adept and easy to work with. If you find yourself wondering whether a referral is necessary or not, just refer the patient. It’s better to be safe than sorry, and a second set of eyes is often very helpful.

Communicate your diagnosis to the patient.

Walk the patient through what you’re thinking. Explain your reasoning by drawing on everything you’ve learned thus far. If you aren’t super confident in your working diagnosis, that’s okay. Just tell them where your head as it and address the potential paths forward, including what you plan on doing to gather more information. Point out the tests that were already performed to show the reason for the problem. Explain how these evaluations confirmed your diagnosis and show conclusive evidence. Use factual information, such as test result quotes, to back up your identification of the patient's issue. Identify the organic issues (if any) that influenced the decision for this diagnosis.

Document the diagnosis in their file.

Put your plans and diagnosis into their medical file. This way, other practitioners will be able to rule things out and take your results into account if this comes up in the future. It also makes it easier for you to remember what you’ve already looked at, though. You may see hundreds of patients before this patient comes back, so document everything you do.

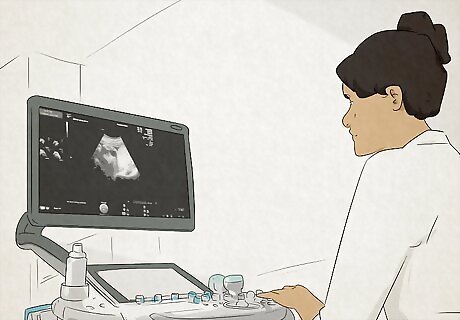

Confirm the diagnosis through treatment or testing.

The steps here depend on the nature of the working diagnosis. You might order bloodwork to look for a hormone imbalance you expect to find, or refer the patient for an X-ray to find a bone break you think there may be. Regardless, order or perform the tests you need until you can either confirm or rule out your working diagnosis. If you confirm your working diagnosis, great! Move on to treatment and explain the prognosis for the patient. If you end up ruling out your working diagnosis, the entire process starts back over again. Use what you learned up to this point to inform your new working diagnosis and continue to gather more information. This entire process can take 3 minutes if it’s straightforward. However, it can take months depending on how complex or elusive the underlying problem is.

Explain the treatment options to the patient.

Once you have an answer, walk the patient through the treatment. There may be medication you can prescribe to manage the symptoms, or a surgical procedure the patient could undergo to permanently resolve the problem. In any case, it’s up to the patient to choose a course of action now. Explain the pros, cons, and risks of each option. Offer your recommendation, but honor the patient’s wishes if they don’t agree with you. If the patient is in denial, you can always suggest they get a second opinion. Doing nothing is also an option depending on the issue. “This should go away on its own” is a totally valid course of action.

Comments

0 comment