views

Getting Out of the Water

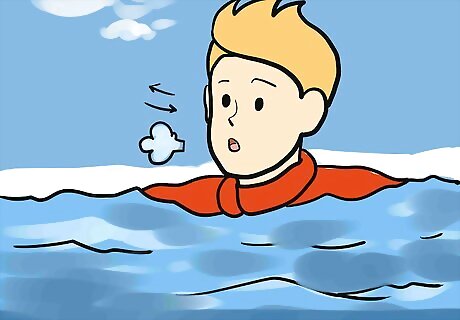

Brace yourself. Once you have the sickening realization that you're falling through the ice and into the cold water, you need to brace yourself and consciously stop your reflex to gasp and breathe in if your head gets submerged. The shock of being in freezing water should not be underestimated, as it causes immediate changes to your breathing and heart rate. Immediately call for help if there are other people around. Once in the cold water, your body's cold shock response, called the "torso reflex," will make you want to gasp for air and hyperventilate because your heart rate accelerates rapidly, but you must avoid doing so, especially if you're underwater. This initial shock typically wears off in one to three minutes as your body slightly acclimatizes to the cold. Although the initial cold shock passes, you're still in grave danger of quickly developing hypothermia, which means your body loses heat faster than it produces it. Just a 4-degree drop in body temperature can trigger hypothermia.

Keep as calm as possible. The physical pain of being submerged in freezing water combined with all the physiological changes in response to "cold shock" (increased heart and breathing rates, high blood pressure, adrenaline release) can easily lead to panic. However, remaining calm and controlling your breathing allows you to think better and develop a plan to get out of the water. Take deep and slow breaths after the initial shock so you’re less likely to panic. You don't have a lot of time, but likely more time than a panicky mind perceives. Hypothermia occurs as your body temperature passes below 95°F (35°C), but it takes some time to get there and depends on many factors. Keeping your head above water and as much of your body as possible out of the water will buy you more time. Depending on multiple factors such as physical conditioning, the amount of body fat, type and layering of clothing, ambient temperature, and wind chill, it can take between 10 to 45 minutes to develop hypothermia and lose consciousness in cold water. Remove any heavy objects or clothing that are weighing you down, such as a backpack, fanny pack, or skis. This will reduce your risk of drowning.

Focus your energy on getting out immediately. Once you have calmed down and your head is above the water, you must focus your energy on getting out as quickly as possible rather than treading water and waiting for help. Move your legs like you’re riding a bike and keep your head above water by tilting it back. Orientate yourself and focus on getting back to where you fell in, as the other edges are probably sturdy enough to support you getting out. Remaining in the water can shorten your survival time by 50% Try to orient yourself to the place where you fell through the ice and lift your arms in the air as high as you can so other people see you. If underwater, always look for contrasting colors. When the ice is covered with snow, the hole will appear darker; ice without snow will make the hole look lighter. In most cases, neuromuscular cooling or "swim failure" is a bigger and more immediate concern than hypothermia. In essence, most people will have between three and five minutes before the cold water incapacitates their muscles and coordination, making it very difficult or impossible to swim and kick their legs. If you are with other people, yell loudly to let them know you've fallen in. They may not be willing or able to help you, but at least they won't abandon you and might be able to make an emergency call from their cellphone.

Get horizontal and kick your legs. Once you're orientated and decide where you're going to exit the water, quickly swim towards it and grab onto the edge of the ice. Get as much of your upper body as possible out of the water. Grab onto the top of the ice and use your forearms and elbows to prop yourself up. Then position your lower body horizontally and kick your legs as forcefully as possible in hopes of propelling yourself out of the water and onto the ice — much like seals in the arctic do. Once you've lifted your upper body onto the edge of the ice, wait a few seconds to let your clothes drain as much water as possible. It will reduce your weight and make it easier for you to actually propel yourself out of the water. If you're unable to get out of the water after about 10 minutes, then you're almost certainly not going to get out by your own efforts as swim failure and hypothermia will be upon you — but don't panic at this stage either. If you can't get out by yourself, conserve your energy (and heat) by moving as little as possible and wait for rescue. Cross your legs to conserve heat and try to keep your arms out of the water, as your body loses heat 32 times faster in cold water than in cold air.

Roll your body across the ice and away from where you fell in once you're out. Once you've propelled yourself out of the cold water, then resist the urge to stand up and run for the shore because you may fall in again. Instead, remain spread out on the ice (so that your weight is distributed across a larger area) and slowly roll your body toward thicker ice or hard ground. At the very least, roll away from the hole in the ice by several feet before attempting to stand up. If you can, trace your tracks back to shore or hard ground — it held your weight previously, so it'll likely hold your weight again. Remember that you should always stay off ice that's only 3 inches (7.6 cm) thick or less, especially during warmer days when the ice is thawing. At least 4 inches (10.2 cm) of ice thickness is needed for ice fishing, walking, or cross country skiing, whereas at least 5 – 6 inches is needed to support a snowmobile or ATV.

Surviving Once You're Out

Retrace your footsteps back to safety. Once you're out of the water, only part of your struggle for survival is complete, because hypothermia is likely fast advancing within your body. As such, once on safe footing, quickly retrace your footsteps or path back to shore and/or your vehicle or cabin so you can get warmed up. Your leg muscles will likely not want to cooperate due to the cold shock, so you may have to crawl or drag yourself. Ask for immediate assistance if there are people nearby. They may not have any survival or emergency medical knowledge, but they can at least help you get to a safe place and maybe call for additional help. Initial signs and symptoms of hypothermia include shivering, dizziness, hyperventilation, increased heart rate, slight confusion, difficulty speaking, clumsiness, and moderate fatigue. Signs of severe hypothermia include more advanced confusion, poor decision making, lack of coordination, violent shivering (or none at all), slurred speech or incoherent mumbling, weak pulse, shallow breathing, and progressive loss of consciousness.

Take off your wet clothes once you’re inside. It may seem counterintuitive during the moment, but taking off wet clothes is the fastest way to increase your core body temperature –– assuming you have dry clothes or a source of heat available. An external source of heat can't penetrate wet clothing and warm you up, so remove them quickly and wrap yourself in dry clothes and/or blankets. If you can’t get inside, find an area sheltered from the wind or elements before removing clothing, preferably a dwelling or a vehicle. If not, then stand behind some trees, rocks, or a snowdrift to protect yourself from the additional chill of the wind. If you are only in the early stages of hypothermia and still feel like you have some excess energy, do some push-ups or basic calisthenics after removing your clothes in an attempt to warm up and improve blood flow.

Get warmed up gradually. Once you've removed your wet clothes, you need to find dry replacements and a source of heat quickly but not all at once. With advanced hypothermia, you may not be shivering any longer or feel very cold. Many patients report feeling numb. If you didn't bring a change of clothes, then ask others for extra clothes, jackets or blankets. Make sure to cover your head and insulate your body and feet from the cold ground. Sleeping bags, wool blankets, or space blankets will help you to conserve body heat and rewarm your body. If you don't have a dwelling or vehicle to get warm in, you'll have to make a fire. Make sure you're out of your wet clothing and into something dry before collecting wood and making a fire. Get people to help if they're nearby. Once you are in front of a heat source (fireplace, heat vents in a vehicle, campfire) bring your knees to your chest and keep your legs tight together to conserve your body heat. If you are with other people, huddle together in a tight circle facing each other in order to share body heat. Drink a warm, sweet, non-caffeinated beverage. The mug will warm your hands and the liquid will warm your insides. If you are using heating pads or hot water bottles, place them near major arteries such as near the groin, armpits, or shoulders. Always place a barrier between the heat source and your skins to prevent any burns. Extreme heat can damage your skin or trigger irregular heartbeats and a heart attack. Remember, you are trying to slowly and safely increase your core body temperature, and this can take a few hours.

Comments

0 comment