views

Determining Factors that Affect Magnetic Field Strength

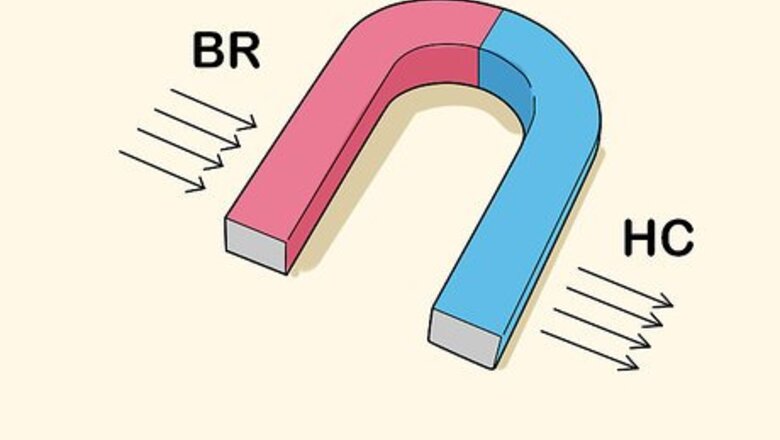

Consider a magnet's characteristics. Magnetic properties are described using these characteristics: Coercive magnetic field strength, abbreviated Hc. This represents the point at which the magnet can be demagnetized (degaussed) by another magnetic field. The higher this number, the more difficult it is to degauss the magnet. Residual magnetic flux density, abbreviated Br. This is the maximum magnetic flux the magnet can produce. Related to magnetic flux density is overall energy density, abbreviated Bmax. The higher this number is, the more powerful the magnet. The temperature coefficient of the residual magnetic flux density, abbreviated Tcoef of Br and expressed as a percentage of degrees Celsius, describes how the magnetic flux decreases as the magnet's temperature rises. A Tcoef of Br of 0.1 means that if the magnet's temperature rises 100 degrees Celsius (180 degrees Fahrenheit), its magnetic flux decreases by 10 percent. The maximum operating temperature (abbreviated Tmax) is the highest temperature the magnet can be operated at without losing any of its field strength. Once the temperature falls below Tmax, the magnet recovers its full field strength. If the magnet is heated above Tmax, it will lose some of its field strength permanently after cooling to its normal operating temperature. If, however, the magnet is heated to its Curie temperature, abbreviated Tcurie, it will become demagnetized.

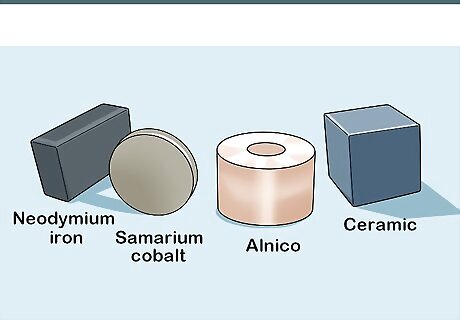

Note the material a permanent magnet is made from. Permanent magnets are typically made from one of the following materials: Neodymium iron boron. This has the highest magnetic flux density (12,800 gauss), coercive magnetic field strength (12,300 oersted), and overall energy density (40). It has the lowest maximum operating temperature and Curie temperature, at 150 degrees Celsius (302 degrees Fahrenheit) and 310 degrees Celsius (590 degrees Fahrenheit), respectively, and a temperature coefficient of -0.12. Samarium cobalt has the next highest coercive field strength, at 9,200 oersted. But it has a magnetic flux density of 10,500 gauss and an overall energy density of 26. Its maximum operating temperature is much higher than for neodymium iron boron at 300 degrees Celsius (572 degrees Fahrenheit), as is its Curie temperature of 750 degrees Celsius (1,382 degrees Fahrenheit). Its temperature coefficient is 0.04. Alnico is an aluminum-nickel-cobalt alloy. It has a magnetic flux density close to that of neodymium iron boron (12,500 gauss), but a much lower coercive magnetic field strength (640 oersted) and consequently an overall energy density of only 5.5. It has a higher maximum operating temperature than samarium cobalt, at 540 degrees Celsius (1,004 degrees Fahrenheit), as well as a higher Curie temperature, 860 degrees Celsius (1,580 degrees Fahrenheit), and a temperature coefficient of 0.02. Ceramic and ferrite magnets have much lower flux densities and overall energy densities than the other materials, at 3,900 gauss and 3.5. Their magnetic flux density, however, is much better than alnico at 3,200 oersted. Their maximum operating temperature is the same as for samarium cobalt, but their Curie temperature is much lower, at 460 degrees Celsius (860 degrees Fahrenheit), and their temperature coefficient is -0.2. Therefore, they lose field strength faster in heat than do any of the other materials.

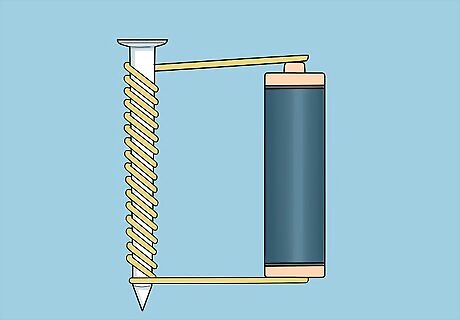

Count the number of turns in an electromagnet's coil. The more coil turns per length of the core, the greater the magnetic field strength. Commercial electromagnets have sizable cores of one of the magnetic materials described above and large coils around them. However, a simple electromagnet can be made by wrapping a coil of wire around a nail and attaching its ends to a 1.5-volt battery.

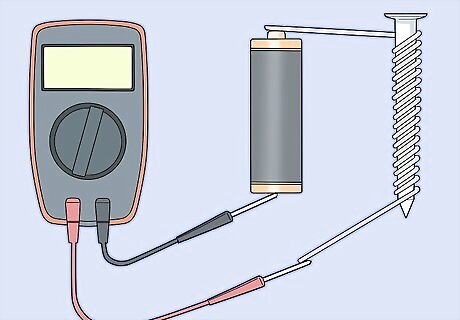

Check the amount of current flowing through the electromagnetic coil. Use a multimeter to do this. The stronger the current, the stronger the magnetic field generated. Ampere-turn per meter is another metric unit for measuring magnetic field strength. This represents how if the current, the number of coils, or both are increased, the magnetic field strength increases.

Testing Magnetic Field Range with Paperclips

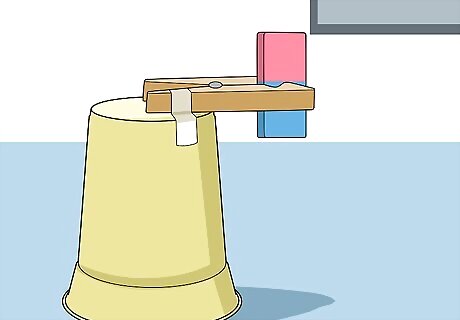

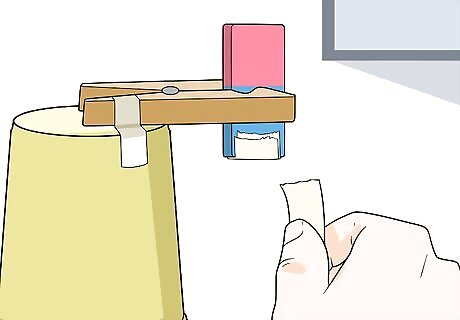

Make a holder for a bar magnet. You can make a simple magnet holder using a clothespin and a paper or Styrofoam cup. This method would be suitable for teaching elementary school-age students about magnetic fields. Tape one of the long ends of a clothespin to the bottom of the cup. Place the cup with the attached clothespin on the table upside down. Insert the magnet into the clothespin.

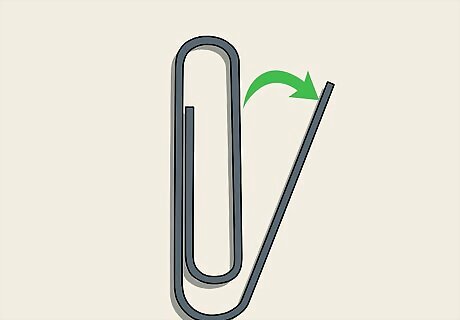

Bend a paperclip into a hook. The easiest way to do this is to pull out the outer end of the paperclip. You will need to be able to hang more paperclips from the hook.

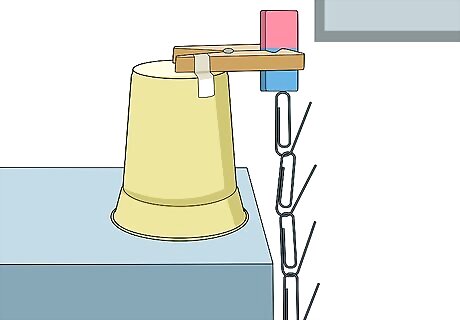

Add further paperclips to measure the strength of the magnet. Touch the bent paperclip to the magnet at one of its poles. The hook portion should hang free. Hang paperclips from the hook. Keep doing this until the weight of the clips causes the hook to fall.

Note the number of paperclips that caused the hook to fall off. When you have added a sufficient number of paperclips and the hook falls off the magnet, carefully write down the exact number of paperclips that caused this to happen.

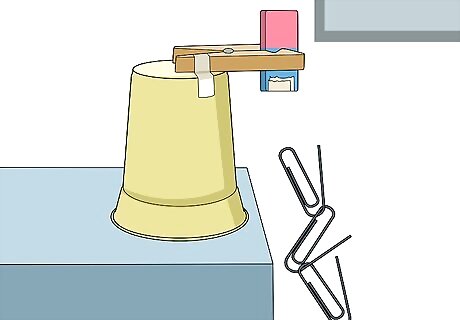

Add masking tape to the magnet pole. Put 3 small strips of masking tape over the magnet's pole and hang the hook from it again.

Add paperclips to the hook until it falls off the magnet. Repeat the previous method of hanging paperclips from the original paperclip hook, until it eventually falls off the magnet.

Write down how many clips it took to make the hook fall this time. Make sure you note both the number of masking tape strips and the number of paperclips used.

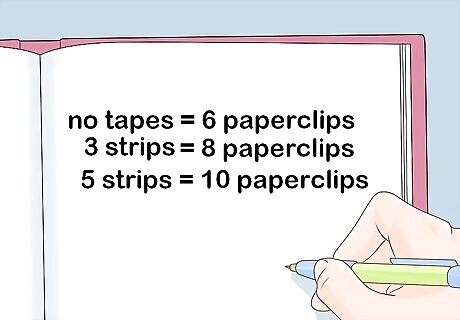

Repeat the previous steps several times with more strips of masking tape. Each time, note the number of paperclips it took to make the hook fall off the magnet. You should notice that as you added strips, it took fewer and fewer clips to make the hook fall off.

Testing Magnetic Field Strength With a Gaussmeter

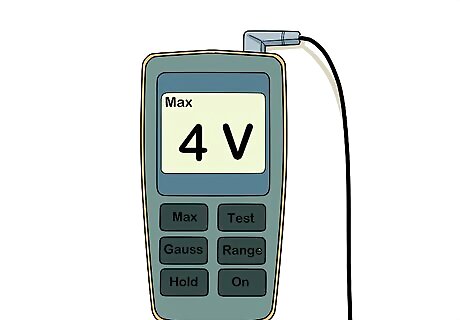

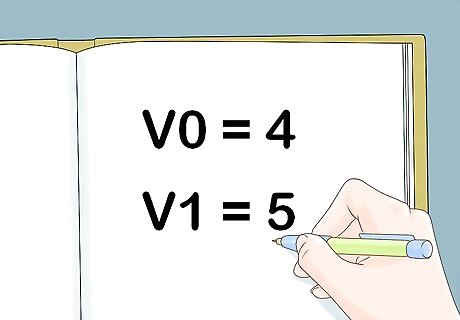

Calculate the baseline or original voltage. This can be done using a gaussmeter, also known as a magnetometer or an EMF detector (electromagnetic field detector), which is a hand-held device that measures the strength and direction of a magnetic field strength. They are readily available to buy and simple to use. The gaussmeter method is suitable for teaching middle school and high school students about magnetic fields. Here's how to start using one: Set the maximum voltage to be read at 10 volts DC. Read the voltage display with the meter away from a magnet. This is the baseline or original voltage, represented as V0.

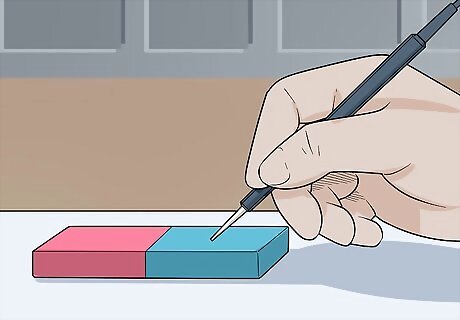

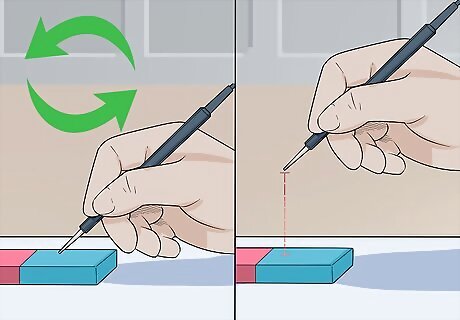

Touch the meter's sensor to one of the magnet's poles. On some gaussmeters, this sensor, called a Hall sensor, is built into an integrated circuit chip, so you touch the magnet's pole to a sensor.

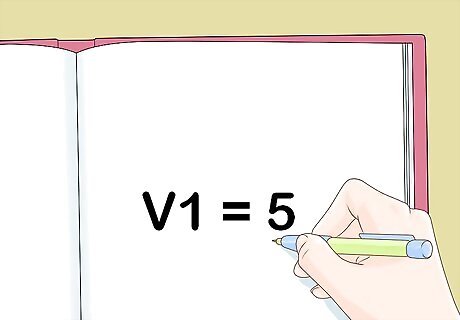

Record the new voltage. Represented by V1, the voltage will either go up or down, depending on which pole of the magnet is touching the Hall sensor. If the voltage goes up, the sensor is touching the magnet's south-seeking pole. If the voltage goes down, the sensor is touching the magnet's north-seeking pole.

Find the difference between the original and the new voltage. If the sensor is calibrated in millivolts, divide by 1,000 to convert from millivolts to volts.

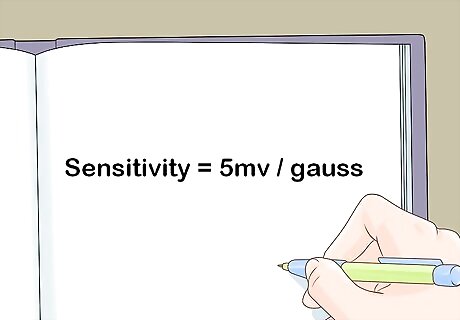

Divide the result by the sensitivity value of the sensor. For example, if the sensor has a sensitivity of 5 millivolts per gauss, you would divide by 5. If it has a sensitivity of 10 millivolts per gauss, you would divide by 10. The value you receive is the field strength of the magnet in gauss.

Repeat to test the field strength at varying distances from the magnet. Place the sensor at a series of defined distances from the magnet's pole and record the results.

Comments

0 comment